Introduction

'Are we tac or non-tac?' It sounds like an easy question to answer, but when you have soldiers being ordered to apply bush-style camouflage in urban carparks, take a knee and whisper in secure rear-echelon positions, or use white light in a night harbour, the answer isn’t always apparent.

The communication and enforcement of expected tactical behaviours is often a set of constantly moving goalposts, left to the personal experiences and interpretation of the commander or observer/trainer present with that particular group at the time. This creates ongoing inconsistencies which can negatively affect everything from maintenance of rest cycles to overall operational security. Let's contrast this with how we approach other tactical measures. For example, by using the Force Protection Measures outlined in the Standard Infantry Battalion (SIB) field handbook as part of the orders process, soldiers are left with no doubt how to wear their armour and other personal protective equipment (PPE).

This article proposes that a similar framework of measures be created to counter the lack of structure around tactical behaviours. These 'Tactical Behaviour Measures' would provide a baseline level of consistency that is easily understood and actioned, offering a range of benefits that are already demonstrated by the Force Protection Measures:

- Soldiers can quickly align their behaviours as per orders, removing any ambiguity.

- Soldiers and commanders can hold each other to account, given the clear expectations provided.

- Levels can be assigned to phases as required, providing flexibility within a framework and matching the tactical posture to the situation.

- Soldiers can quickly get reinforcing or external parties up to speed with the local environment expectations upon entry to their area of operations.

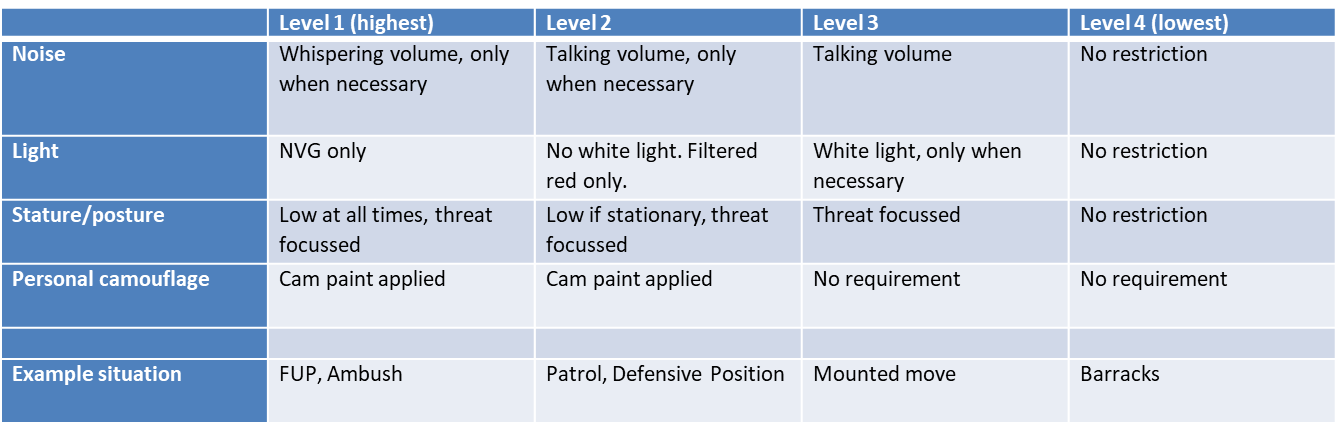

It should be noted that this article is designed to introduce the concept of a Tactical Behaviour Measures framework, with the below measures (noise, light, etc.) and levels being examples only for the purpose of demonstration, rather than hard suggestions for doctrine.

Quantifying Tactical Behaviour Measures

The existing Force Protection Measures provide guidance on a limited but vital range of personal equipment – helmet, armour, and weapon. By keeping the structure simple, it is easily employed as a baseline set of guidance. The proposed Tactical Behaviour Measures take a similar approach, balancing simplicity while being inclusive of a limited but vital range of behaviours displayed by soldiers and being applicable across a wide variety of scenarios.

Below are examples of tactical behaviours and, as per the Force Protection Measures, what could be expected at four levels. While it is anticipated that often the levels between the two will match, providing separate tables allows flexibility as required.

Applying Tactical Behaviour Measures

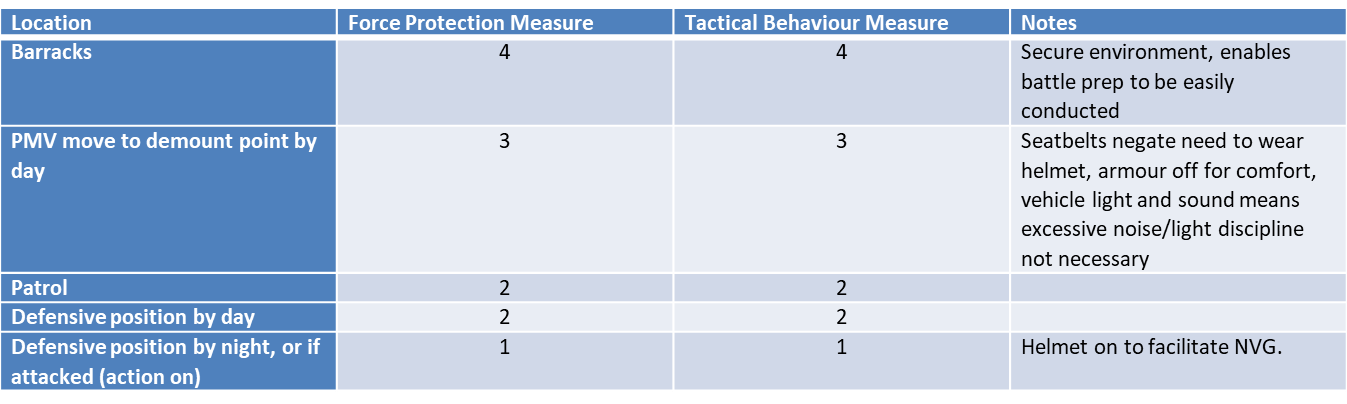

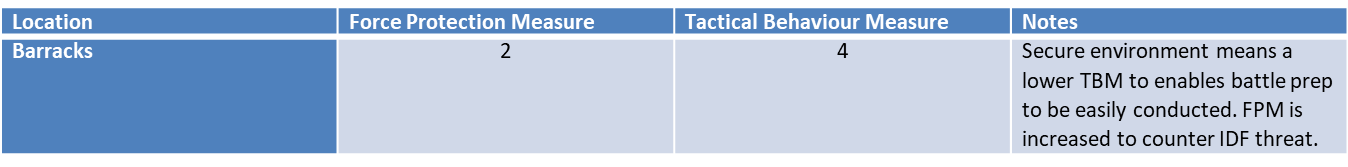

The following two scenarios show how these measures can be applied in the field and incorporated into orders.

Scenario 1. Soldiers are in a secure barracks environment. They are preparing for a mounted move, followed by a short patrol to occupy a defensive position by day, then transition to night routine.

Scenario 2. Soldiers have occupied a FOB that has hesco walls and guards, however due to the location the FOB is under constant threat of Indirect Fire.

Keep it simple so soldiers can focus on the job

Keep it simple. We hear it all the time, yet in situations like tactical behaviours the reality is anything but. By providing a simple structure, ambiguity is removed and the soldiers have no doubt as to what is expected of them. Keep in mind that, as with all the Force Protection Measures - 'While force protection measures will vary according to mission profile, this standard operating procedure (SOP) provides a useful start point for the SIB.' (SIB field handbook)

This baseline standard has the added advantage of providing a framework for commanders and observer/trainers to provide feedback, allowing them to be consistent in their approach. There is nothing more annoying or ineffective than following the feedback of an observer/trainer (OT) during an exercise only to have another correct you with a different standard on the same point 10 minutes later.

Conclusion

The LWP-G 0-2-4, All Corps Junior Commanders Aide-Memoire, 2003 refers to ‘hard-won lessons’ delivered from various operational experience, and tactical behaviours are no exception. The issue with relying on experience to inform behaviours in the field is that experience takes time, and everyone’s experience is different.

The inclusion of a simple table of personal Tactical Behaviour Measures in the SIB field handbook alongside other Force Protection Measures would turn experience into doctrine, and provide a baseline standard of behaviour in both training and operations. It could be easily incorporated into the SMEAC orders format, allow enough flexibility within its framework to be useful in scenarios from barracks to battlefield, and would finally put to bed the persistent irritation that is the ‘semi-tac’ environment.

However I don’t think that a framework of measures would fix the problem, rather it will simply codify the requirement to “apply bush-style camouflage in a urban carparks” into an easily understood matrix.