Note from the Cove Team: This is a follow up article from Daniel Kirkham, check out his first article, Fighting Hybrid Threats: Lessons Learnt from DATE

Introduction

‘Being confronted with this completely new concept of warfare, there is no doubt that the impression of war to which people have already become accustomed will be shaken. Some of the traditional models of war, as well as the logic and laws attached to it, will also be challenged.’ - Unrestricted Warfare [1]

Our Army prides itself on being Manoeuvre Warfare force, now tasked with adapting to new threats at an ‘accelerated’ rate. We have long understood that our primary purpose for fighting is to defeat, and this is achieved using indirect approaches to target the enemy’s ‘will’, rather than by pursuing their complete annihilation. One way we express this is in the foundational concept of ‘dislocation’; or the avoidance rather than confrontation of enemy strengths, in order to render those strengths irrelevant or dysfunctional[2].

This idea informs our faith that our comparatively smaller forces, even if equipped with average, or substandard weapons and equipment, may defeat a larger adversary if we deny them the opportunity to bring their superior numbers and plan to bear. And yet, our current tactics are in danger of being dislocated. Alternative approaches, such as those seen in ‘Systems Warfare’, or ‘New Generation Warfare’ strategies, display a better understanding of how to coordinate all tools of national power to dislocate an opponent’s will to fight beyond traditional battle alone.

It is important we understand how alternate concepts of warfighting are being developed around the world if we are to develop demanding and realistic training environments that prepare our people for the challenges of the future. This Part 2 article on the Hybrid Threat will continue discussing how Army should employ DATE to train against contemporary threats, instead of simply training to fight ourselves, so that readers can better prepare themselves for their next Combat Team or Battlegroup Warfighter rotation with CTC, or a real world scenario.

Hybrid Warfare in our Region

‘The Western allies and their partners did not possess well-developed capabilities for combating hybrid warfare and were not well-placed to punch back or outflank the Chinese campaign. - Ross Babbage[3]

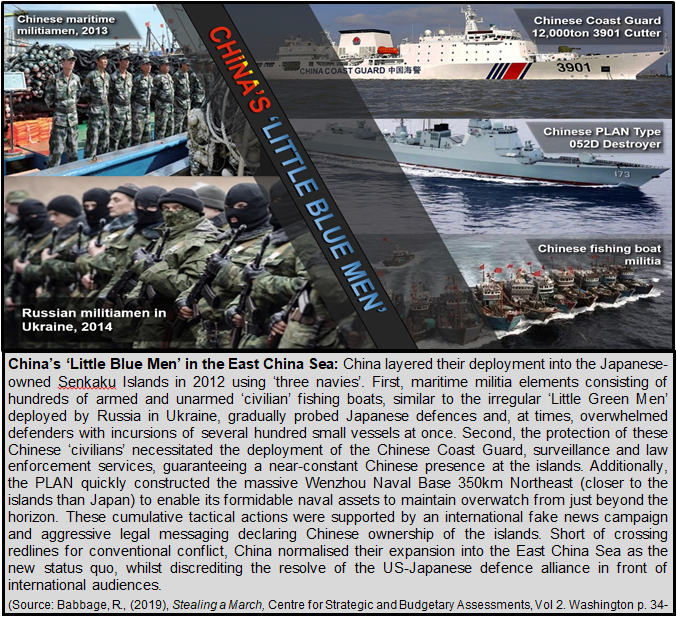

In just six years, from 2012 to 2017, China has increased its influence in the strategically vital South and East China Seas by using hybrid warfare tactics to dislocate conventional military responses. China’s synchronisation of tactical level actions with economic, political and informational coercion is synonymous with their whole of ‘system’ approach to warfare. The 1999 book ‘Unrestricted Warfare’, the 2003 ‘Political Work Guidelines of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA)’ on ‘Political’, ‘Legal’ and ‘Public Opinion’ Warfare, and the PLA’s own 2015 ‘Systems Destruction Warfare’ doctrine are all important texts that permeate current thinking within the PLA[4]. They are indicative of a Chinese approach to indirect/protracted warfare routed in Maoist Marxism-Leninism of the early 20th Century.

The current doctrine calls for employing non-military ‘warfares’ such as ‘Economic Warfare, Electronic Warfare, Psychological Warfare, Political Warfare, Legal Warfare and Terrorist Warfare’ with ‘Conventional Warfare’ in unexpected ‘combinations that transcend boundaries’, or in other words achieve dislocation[5]. China views an adversary’s national power as a ‘system of systems’ that can be ‘rendered ineffective or outright unable to function through the destruction or degradation of critical capabilities, weapons, or units that compose the system’. An opposing nation’s system can ‘lose its will and ability to resist once it cannot effectively function’[6]. We could equate this to our own expression of exploiting ‘critical vulnerabilities’ to dislocate enemy strengths in order to target an enemy’s ‘Centre of Gravity’, or ‘will to fight’[7]. Unsurprisingly, these hybrid warfare tactics share rough similarity to those well-understood tactics used by Russia to push Ukraine to the brink of defeat in 2014, as covered in Part 1 of this article. These correlations provide us a structure to conduct our own comparison against our organisational and philosophical approach to tactics.

Hybrid Warfare & Manoeuvre Warfare - A Brief Comparison

‘Today’s army is well equipped for the protective fight against enemy armed forces. It has, however, severe limitations when pitted against… dislocation warfare...’

- Robert Leonhard [8]

Whilst there is no universal Chinese or Russian ‘way of war’, in a similar manner to Manoeuvre Warfare, both place emphasis on the concept of dislocation. Yet, while Australia pursues the tenets of manoeuvre with a bias for traditional combined arms tactics that force defeat through multiple cumulative physical engagements, we are arguably outpaced by competitors who employ more sophisticated dislocation bordering on the pre-emptive. They employ combined arms manoeuvre, but exercise greater innovation and great focus on the will of defenders in pursuit of defeat as a psychological state, demonstrating a superior understanding of ‘winning without fighting’:

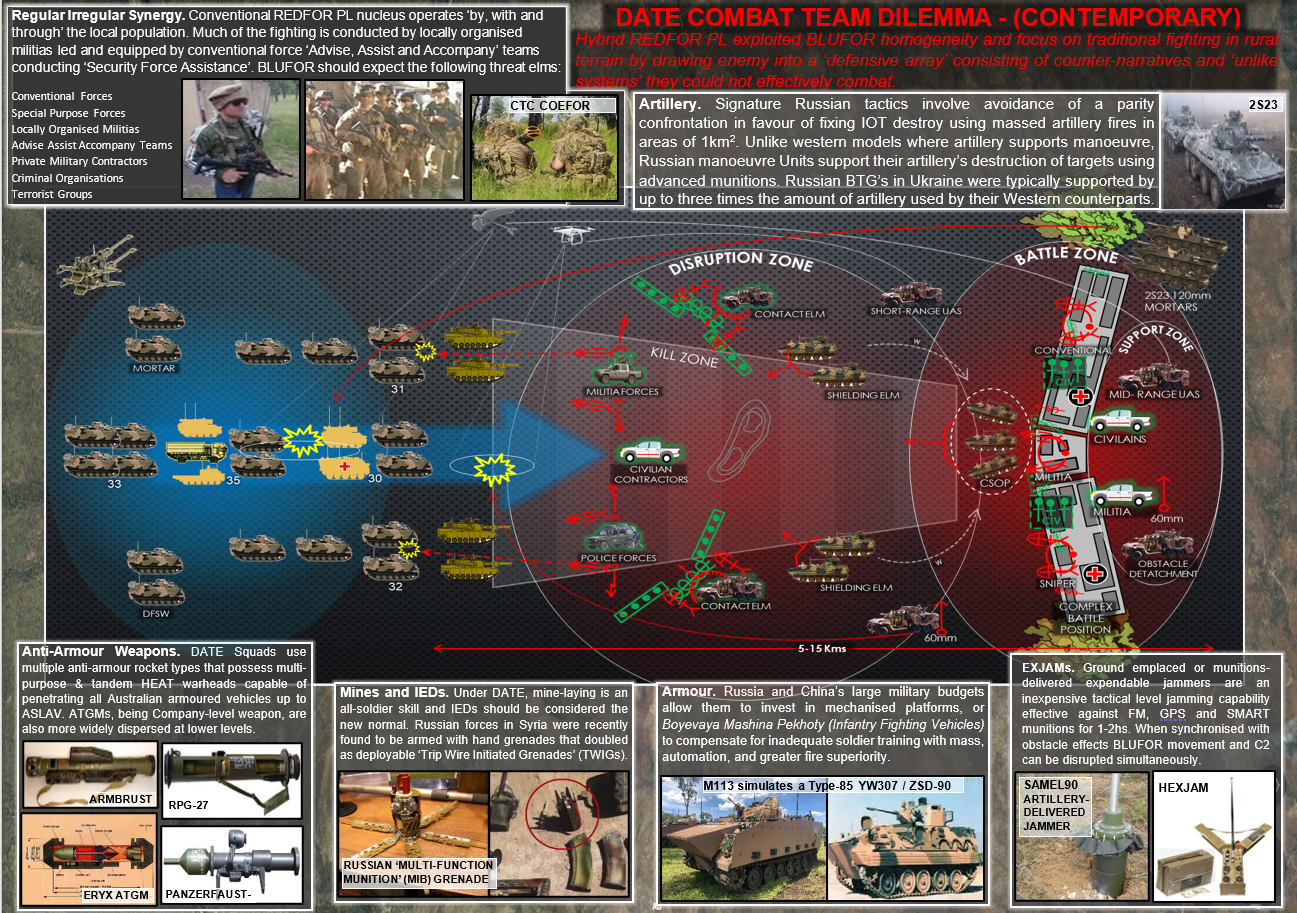

- Both Russian and Chinese approaches maintain ‘Tempo’ through fluid integration of low-tech para-military sympathisers, criminals and private contractors, with high-tech Special Operations Forces, Electronic Warfare (EW), Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS), Integrated Air Defence (IAD) and massed indirect fires[9]. This flood of controlled chaos fulfils reconnaissance, sabotage and destruction requirements, and produces a higher relative rate of action that overwhelms the physical and cognitive capacity of defenders to respond.

- Both achieve ‘Surprise’ through a far greater emphasis on information operations to control the strategic ‘escalation dynamic’ which isolates their opponents from international support[10]. Laws of Armed Conflict are not explicitly followed, nor is war officially declared. Shaping operations, such as the use of INFOWAR to ferment social upheaval, foster a state of internal collapse as a precondition to the deployment of conventional forces.

- Both employ ‘Recon Pull’ using a layered system of OPs, UAS, EW and IAD sensors fused into an ever shortening sensor-shooter kill chain. In Ukraine, Russia’s targeting cycle followed the process of detection to enable destruction by overwhelming indirect fires, followed by electronic exploitation of radios, cell phones and social media, culminating in the advance of armoured Units to consolidate gains, whereby the cycle would commence once again.

- Both Russia and China ‘Task Organise’ combined arms ‘systems of systems’, though they exceed us in their readier use of cyber warfare, long range fires, and space systems. In the Russian case agile militias and armour-heavy Battalion Tactical Groups used blocking tactics (blokirovanie) to support the destruction of adversaries using a much higher proportion of artillery units than their Western counterparts[11].

- Both ‘Orchestrate’ by ensuring tactical actions are synchronised to achieve strategic objectives rapidly, so that conflicts can be terminated quickly in order to minimise vulnerability to intervention by more powerful international alliances.

- Both target ‘Centres of Gravity’ by transcending the requirement for physical annihilation in favour of waging war on the ‘battlespace of the mind’[12]. Stakeholder perception becomes the targeted Centre of Gravity. Following Russian artillery fire Ukrainian soldiers were texted by name, with the addresses of their families and asked ‘how they liked the artillery’[13]. Meanwhile conventional Russian Units worked alongside sponsored proxies, bribed local oligarchs, private contractors, puppet mayors and shadow governments. The primacy given to these ‘local’ militias grants validity to the conflict as popular uprising that achieves defeat through regime change rather than purely physical battlefield victories.

Understanding modern alternatives to traditional dislocative fighting provides us the best examples of how DATE can be used as a catalyst for our readiness to combat contemporary tactics.

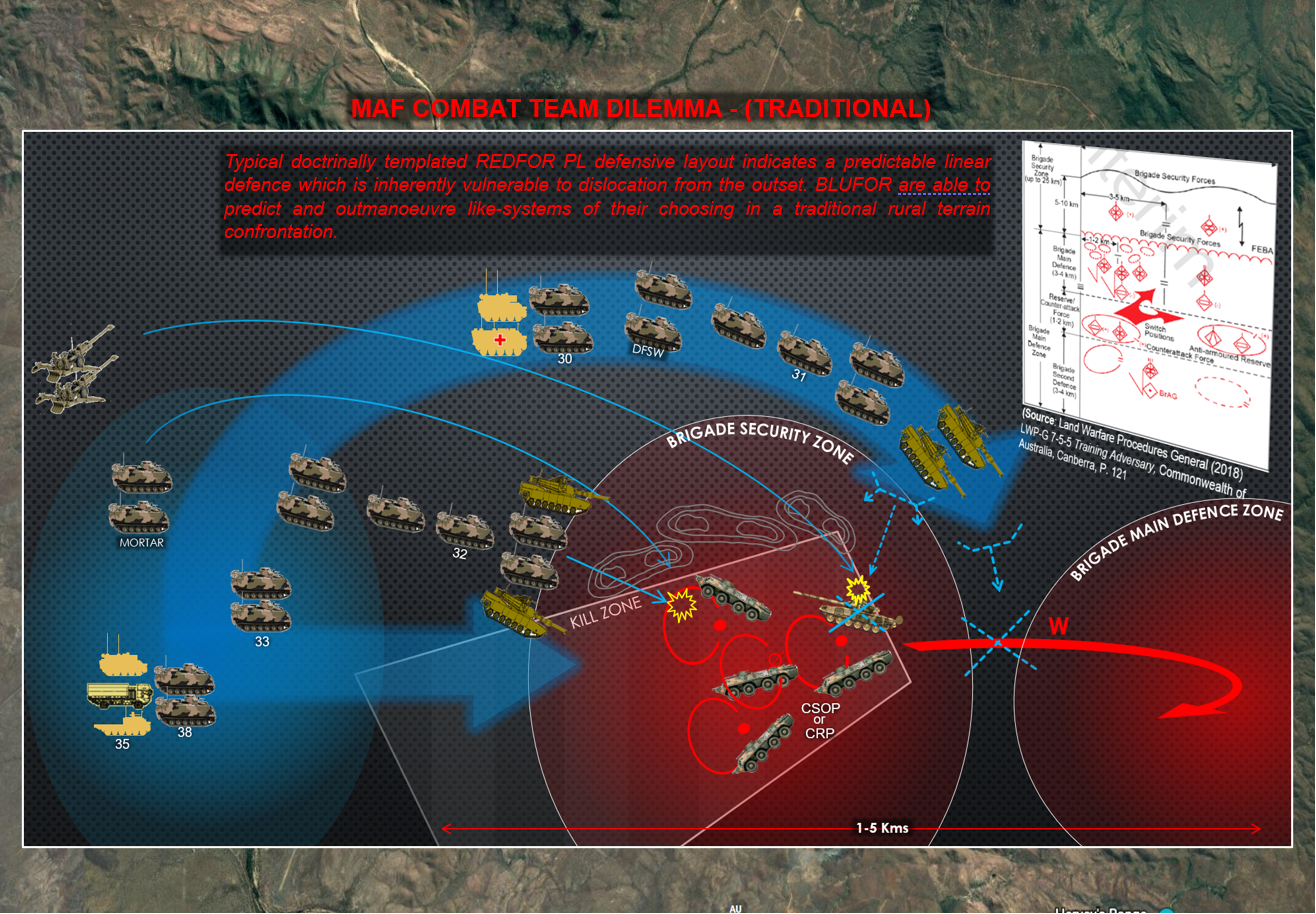

The below images are a comparison of a traditional ‘Musorian Armed Forces (MAF) Combat Team Dilemma’ versus a ‘DATE Combat Team Dilemma’ recently used on a CTC Combat Team Warfighter exercise. Whilst our traditional adversary models are heavily reliant upon doctrinal templating, the DATE dilemma below innovates a contemporary adversary plan that is designed to defeat the BLUFOR training audience. It encapsulates emerging trends including use of proxy/non-state elements, growing urbanisation, information linking and jamming. Its purpose is not conclusive, but illustrative of the direction our current tactical thinking should be advancing:

‘Training situations should be challenging, complex, ambiguous and unpredictable.’- Australian Defence Doctrine Publication 7.0, Training[14]

Army’s subscription to DATE is an acknowledgement of the flexibility, adaptability and complexity unfolding in today’s global power competition, and yet this is not always reflected in our training. Too often in training we are bounded by rationality to adopt certain unwritten rules when thinking about the enemy for the sake of efficiency. Most of the time these heuristics serve us well because they save us time and effort. However, in some cases, our cognitive limitations and intolerance for complexity lead us to retain old learning and leave us ill-prepared for change. Our bias for focusing on decisive battle is a particularly Western formulation that is embedded in our continental European culture, itself derived from classical Greek and Roman systems of politics and warfare, and successively passed on through Western civilisations to the European kingdoms[15]. As well as our principal political tenets such as individual liberty, rationalism, free inquiry and consensual government, the Hellenic concept of constitutionally governed decisive battle, largely based around close order heavy infantry, evolved through time to cement a uniquely Western dominance over organised warfare.

Decisive battle has served us well for its crystallisation of moments that decided the fates of entire campaigns and civilisations. However we have long-recognised that for centuries the utility of traditional decisive battles is diminishing due to rising capabilities in deception, low-intensity attrition, and unconventional asymmetry. This challenge to our entrenched methods can leave us reluctant to complexity and adverse to perceived ‘un-fairness’ in training (expecting the enemy to avoid urban combat, spare HQs, or not to use IEDs because it is too ‘complex’). Our often binary view of conflict as war and peace, or conventional and unconventional warfare, leaves us inflexible and exposed to large cognitive ‘grey areas’ in which competitors can innovate and exploit our focus on fighting traditional battles.

Whilst hybrid warfare at large is occurring on a grand strategic scale below the threshold of open war, the possibility of hybrid combat in our region is not as far-fetched as it may seem. DATE-based competitors such as China, Russia, Iran, North Korea and ISIS, do not lack the combat power to conduct open warfare, but they risk mutual destruction if they vertically escalate towards major conflicts. Rather, horizontal escalation, via protracted, exhaustive and low-intensity proxy wars, remains the best method for aggressors to secure incremental improvements to their competitive positions quickly, and prior to risking total war. Even recently, the COVID-19 crisis has exacerbated existing inequalities amongst the world’s most fragile and low-income populations. It is simultaneously reducing the relative fighting power of states to respond to Chinese expansion in the South China Sea, Russian expansion in Africa, and extremist activity as close as Indonesia.[16] This is a unique time for opportunistic competitors to establish manipulative benefactor-beneficiary relationships with disaffected groups in order to create proxies to further their strategic objectives.

Conclusion

'In all affairs it’s a healthy thing now and then to hang a question mark on the things you have long taken for granted. Many people would sooner die than think. In fact, they do.'

- Bertrand Russell[17]

In the spirit of studying global actors such as China and Russia as innovators rather than enemies, the similarities in their adaptive approaches to contemporary warfare are important developments that transcend mere coincidence. After observing us over a decade of alliance commitments to Middle-Eastern conflicts it is unsurprising to see the development of asymmetries that dislocate our established tactics, as has always been the case of successful military strategies. The philosophical core of our Manoeuvre Warfare doctrine is to pursue psychological defeat, because we understand the purpose of warfare is to collapse an enemy’s ‘will to fight’. Ironically, Russia and China are arguably proving the most adept in the use of this philosophy. Our Army is fixated on perfecting traditional methods of committing our adversaries to decisive close combat with defeat measured in accumulated battlefield losses and ground seized. Yet we have only an elementary tolerance for innovative and free thinking enemies in our training.

At the same time our consideration for connecting our tactical actions with the deeper campaign to defeat the psychological and strategic will of our adversaries is also often an afterthought in our training. Amidst anticipation of rising confrontations in our region we have the opportunity to practice combating hybrid warfare, both with and without the benefits of our greater alliance frameworks. Part 3 of this series will join in with wider Army’s efforts to explore potential solutions to this dilemma. In the short term, commanders and junior leaders will be able to test their own adaptive actions to dislocate the hybrid enemies they encounter on their next CTC Warfighter Exercise. When we are confronted with the unknown we have the chance to rebuild the structures we use to interpret the world on the off-chance our enemies can teach us something that we can use instead of dying.

'Everything that irritates us about others can lead us to an understanding of ourselves.'

- Carl Jung[18]