Being 'frank and fair' with people sounds simple enough that most Australian Defence Force (ADF) leaders are willing to subscribe to the idea and include it in their opening addresses, command philosophies and initial interviews. Outside of these times, when the same commanders are challenged by subordinates who are trying to be frank, fair and fearless in their learning, development, craftsmanship and work outcomes; why do these same commanders retreat and hold their people at arms-length by virtue of rank and authority? Why do they refuse to listen or accept frank, fair and fearless insights from their subordinates? Instead they often dismiss their opinion as inexperience or naivety. Perhaps the answer lies in our culture.

In Outliers, Malcom Gladwell theorises that culture was having a significant impact on airline safety in the 1980-1990s. Gladwell identified that the air safety record of Korean Air was a significant outlier at the time for all the wrong reasons. The reason for their poor safety record according to Gladwell, was their use of ‘mitigated speech’. It was seen as culturally important to not directly challenge authority, in particular when speaking to a superior. Gladwell recounts the final minutes of Korean Air flight 801 and discusses the analysis of the black box recording which reveals several moments where the flight crew used mitigated speech to brief the flight captain of their impending doom. They chose to honour the cultural norm rather than be courageous and save their lives and those aboard the passenger flight.

Gladwell explains that there are varying levels of mitigated speech as can be seen in the following hypothetical example. You are a passenger in a car on a three lane freeway; you are in the middle lane and notice water pooled in your lane ahead. Driving over the water will result in you aquaplaning and possibly spinning. There are at least 6 ways to persuade the driver to change lanes and avoid the water.

- Command: 'Move into the left lane.' The most direct statement.

- Obligation Statement: 'I think we need to change lanes.' Subtle mitigated language.

- Suggestion: 'Let’s go around that water.'

- Query: 'Which lane are you going to move to?'

- Preference: 'I think it would be wise to move into the next lane.'

- Hint: 'That water looks nasty.' The most mitigated statement.

ADF officers, by virtue of rank and appointment, have a habit of enforcing mitigated speech use in almost every exchange between superiors and subordinates. For weak commanders and meek subordinates, interactions with each other are masked as respectful but it is questionable if they are really genuine. This approach has the potential to cause a significantly deleterious effect to the performance of the organisation; without direct honesty our capability suffers. People are afraid of speaking up and saying what is on their mind when it comes to a whole range of things, be it operational planning, exercise conduct, management of sensitive issues or even the benign achievement of corporate governance. However, when leaders genuinely ask and are ready to receive candid feedback, something radical happens. Ideas flow, personnel issues are solved quickly and bureaucratic nonsense is pushed aside in favour of achieving the mission. Another way of describing this comes from our own doctrine. One of the principles of leadership is to communicate and keep your people informed. The doctrine articulates that subordinates will look for logic in orders and in a high trust environment should question where this logic is absent. This questioning, when it occurs, could be described as candour.

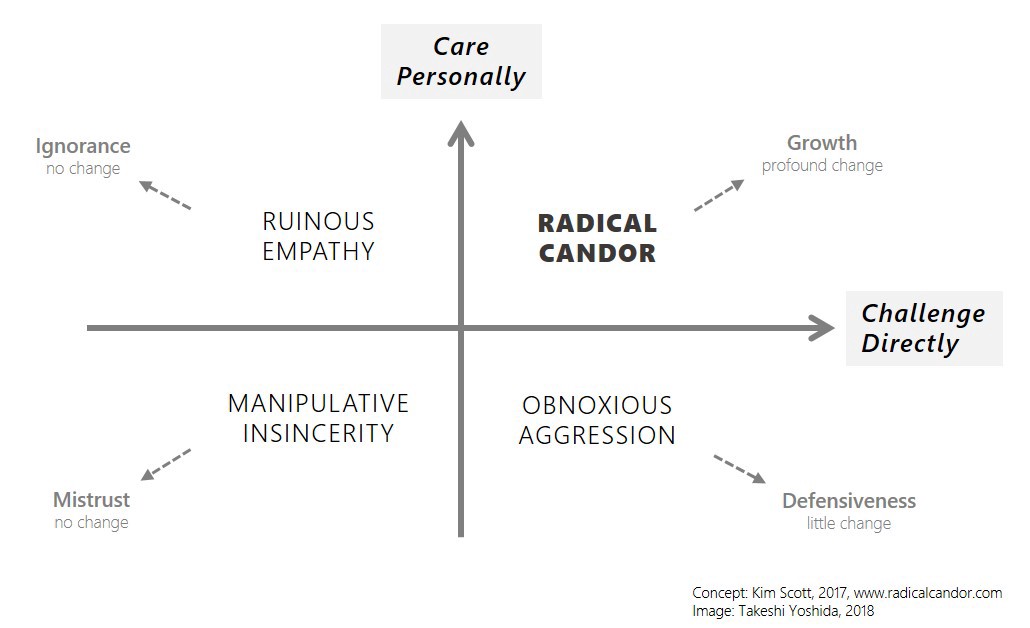

Kim Scott, a long-time director at Google, cofounder of Candor Inc. and author of Radical Candor – How to be a Kick ass boss is a crusader for being frank and fair in the modern workplace. Her book speaks to the ideas of giving a damn (Caring Personally) and providing constructive criticism (Challenging Directly) to help people grow. Scott has also presented her ideas at a number of leadership conferences, find an example here. Key to her theory is the four quadrant diagram in figure 1.

Figure 1, Scott's Graph

Scott’s graph results in the following four quadrants:

- Radical Candour. Having empathy for your people and challenging them to do their best.

- Obnoxious Aggression. Failing to have empathy, but constantly challenging people.

- Manipulative Insecurity. Failing to have empathy or challenge people.

- Ruinous Empathy. Failing to challenge.

Superior commanders who can tolerate non-mitigated speech and radical candour, as Scott identifies, are far more capable of accepting advice from subordinates and have a significantly higher rate of mission achievement. Those same commanders are also ready for personal growth and to receive accurate feedback on their performance as a commander. Further, they create high trust environments which foster innovation, initiative and good tempo in sound decision making. This idea is supported by Tim Jones in his Grounded Curiosity blog post about Driving Innovation Forward. Jones states that for innovation “The key enabler… is a command culture that doesn’t punish ‘failed’ experiments.” This translates into allowing subordinates to be candid and take risks in order to learn. Subordinates who are capable of being candid are also more confident in their daily interactions with their superiors and are far more likely to openly discuss their weaknesses and seek development opportunities.

Interestingly, one of the common idioms taught to junior officers in training is to ‘act as if’ or rather 'to fake it until you make it'. There is no denying that confidence breeds confidence; however the danger with this mentality is that too often the false confidence becomes arrogance, and has no backing in knowledge, skill or talent. That arrogance then becomes the can do attitude that our small defence force is famous for, but for all the wrong reasons. I have witnessed peers and superiors lie directly to their superiors in spirit of the ‘can do’ attitude and to save face in absolute fear of failure. I believe that if they had been able to be candid in their advice and daily exchanges they would have identified that they had room for personal growth and greater mission accomplishment. Instead they persisted with mitigated speech and arrogantly faked it until they made it... often until they could get out of the room. Ultimately, they failed to inspire their commander to honour their agreement to be frank and fair.

The path of change for the ADF, when it comes to candour is simple: allow your people to explore what it feels like to speak to you as a person. This may find them walking dangerously close to being insubordinate or being overly familiar. Teach, coach and mentor them to find the line, show them how you do it with your superiors, and correct them in a constructive way when they get it wrong.

To conclude, if you subscribe to the idea of being frank and fair, ask yourself the following questions:

- Am I as honest with my subordinates and myself with regard to my performance as I can be or am I afraid to reveal my true self?

- Can I inspire my subordinates to me more candid with me by showing them candour with my superior?

- What am I not getting from my subordinates by accepting their use of mitigated speech?

I was/am a big fan of providing Commanders frank and fearless feedback, IOT achieve operational outcomes, or look after my subordinates, sometimes to my detriment.

My statement upfront was "I won't always tell you what you want to hear, but I'll always tell you what you need to know."

I believe that some of the identified reticence by some leaders stems from a combination of factors.

1. Planning cycle lead times.

Once a Commander has embarked on a plan that he/she has delivered, and the troops have had time to experience it's efficacy and assess what could be improved upon, it's already well advanced in its trajectory, and may require significant planning and restructuring to implement the identified changes.

2. Command posting tenures.

Typically, commanders are given a two year tenure in a leadership posting, during which time they must implement their planned improvements and deliverables, IOT be considered for promotion. Whilst a revision of the original plan might yield better operational outcomes, the risk to the Commander is that they may not be delivered during their tenure, due to point 1.

I'm probably going to ruffle some feathers by suggesting that the rectification for this, would be a three year posting tenure for Commanders. Everyone has their own plan, but without allowing them any time to test and adjust their plan, the expectation Army is putting on these Officers, is to get a one shot, one kill first time they step up to the mound.

Receivers of feedback need to be trained how to accept and deal with feedback that will be emotive. That requires training in emotional maturity, but it also needs to be relevant to the age and competency of the group.

The provider of candid feedback needs to be realistically trained as well. Over the shoulder commentary or sarcasm needs to be explained, as does mere repetitive applications of clichés.

Lastly, leaders who do not practice humility need to be held accountable as well, something not easily done in military hierarchy driven systems.