The effectiveness of an organisation is often underpinned by its most valuable capability, its people. To guide this capability, we need effective leaders that can adapt to the changing socio-political landscape but more critically, the character of war (Clausewitz, 1956). Leadership, the hearts and minds approach that fosters followership in a way that management alone cannot achieve. Kempster (2009) argues that leadership can be learnt but as an organisation, are we capturing that intellectual property and sharing experiences across all rank levels? More importantly, are we leading effectively and unlocking the potential of our teams to be ready now and future ready? (Army in Motion, 2019) Leadership is an integration of many factors including vision, functional needs, leadership style, culture and environment as described by the Army Leadership Model (LWD 0-0). To accurately understand leadership, Grint (2005) depicts four different approaches to understanding leadership; person (who), result (what), position (where) or process (how). In his theory, he considers which of the above four areas make an individual a leader. Since person and process are intrinsically linked to behaviour, this article will discuss the philosophical side of leadership and recommend principles in the form of the Good Human Model that are congruent with effective leadership.

Doctrine defines leadership as, 'The art of influencing and directing people to willingly achieve the team or organisational goal' (LWD 0-0). Furthermore, leadership definitions commonly include a purpose, being influence for the achievement of a vision or collective goal (Robbins et al, 2017). While there are many variations of the definition from leading theorists, the common underlying theme is influence. Yukl (1999, p. 286), found that the underlying influence process can be described in terms of 'motivating followers'. A commencement address by Retired US Navy Admiral, William McRaven, discusses a form of intrinsic motivation. In the speech he discusses motivation and resilience but interestingly the most notable of his lessons was about the basics, 'make your bed.' The premise being that this first task completed would instil a small sense of pride and lead to the next task of the day.

Well known leadership theorist Simon Sinek (2009) shares a similar perspective to Yukl by looking at how people are influenced, describing elements of motivation. Particularly he found that successful leaders think, act and communicate in the same way. That is, they question ‘why’ and develop a vision or purpose before they consider how to achieve it and what is required. Furthermore, Sinek linked the idea of process with person; “What you do simply serves as the proof of what you believe.” Put simply, you act in accordance with what you believe and others establish a perception of you based on your actions; ‘perception is reality’. Therefore, our character and beliefs set the foundations for our actions and the output of these factors differentiate effective leaders from ineffective leaders.

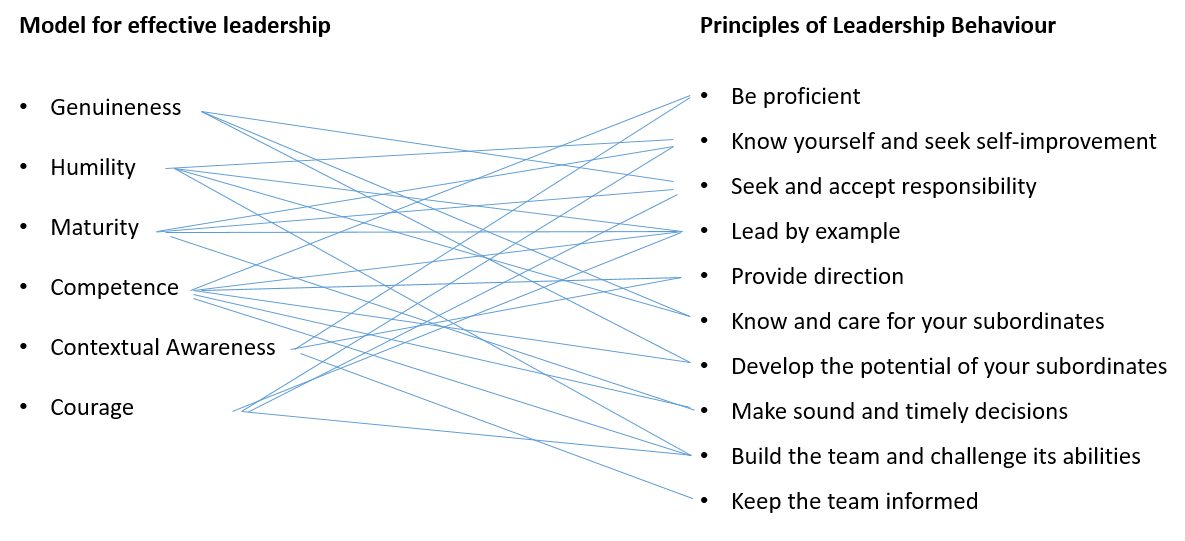

It follows the Principles of Leadership Behaviour Act as a good foundation and useful tool to commanders as they depict the nature of leader who cares for people and develops their own professional mastery (LWD 0-0). This article acts as a reminder that such behaviours are important to be fostered early. Changing behaviour is exceedingly difficult but is far more effective than altering processes and systems (Whitehurst, 2018). To build on these foundations of leadership behaviour with contemporary issues in mind, I recommend leaders consider the following six principles IAW the model at Figure 1:

Genuineness: The foundation of the six principles, a genuine person and an authentic, honest leader who is sincere to others. Authenticity in the sense of integrity, one of the Defence values. At the root of this is respect and your moral and ethical code, being a ‘good human’.

Humility: Recognise that you simply cannot know everything, therefore respect and embrace diversity and the strengths and weaknesses of your team. The junior commander must know their place as influential parts of a unit but also understand they are of less strategic importance than their superiors. Demonstrating humility will support the idea of service and selflessness, placing others before self. The caveat is that you must maintain self-confidence and still recognise your own worth.

Maturity: A high level of emotional intelligence that is evident through your behaviour and interaction with others. This involves behaving in a manner that is suitable to the environment with consideration to time, place and culture. Know your team, understanding their individual situations and being able to empathise, or at minimum sympathise with them. It leads to sound communication and effective workplace relationships that foster strong teams.

Competence: The efficient application of leadership and technical skills based on a foundation of professional and personal excellence. This includes being able to provide purpose and intrinsically motivate subordinates without relying on authority. When this is achieved in part or holistically throughout a task, high quality performance and wellness ensue (Deci, 2017). Communication is particularly important as command and control (C2) is a critical vulnerability at the heart of our fighting ability. One of Army’s modernisation priorities is being connected, this implies the reliance upon technological enhancements but also our human capability, and our people are an elemental component of the force (Langford, 2020).

Whether you are an extrovert and exude charismatic leadership or are an introvert full of creativity and a transformational approach, the pertinent point is applying the right leadership style and motivator (intrinsic or a form of extrinsic motivation) based on the character of the individual and impending task (Cain, 2012). The result should be a team that can function autonomously knowing what they are doing and why in your absence.

Many of the principles of leadership behaviour listed in LWD 0-0 correspond to competence, there are standard expectations of a proficient junior commander (see Figure 2). Bennis (2000) describes four behaviours to improve effectiveness;

- appreciation (recognition) motivates people intrinsically and extrinsically,

- importance (vision) gives people purpose,

- trust enables autonomy and strong relationships, and

- alliance between leader and follower reinforces positive synergy and support from the leader.

Competent leadership from an Army perspective also involves understanding of tactics, effects of different capabilities and how to efficiently plan in complex environments with multiple stakeholders. In addition to this all Corps expectation, we must be able to analyse information and make the right decisions. The tactical sphere is growing at a rapid rate due to the integration of systems and connectivity, subsequently there is a demand for more strategic planning (Langford, 2020). From a technical side, the leader must be proficient within their specialisation or area of expertise.

Contextual awareness: Know your environment and understand different lenses or how you fit into the bigger picture. There is a balance of having a strategic awareness yet understanding the internal aspects of your unit structure, culture and processes while remaining cognisant of external stakeholders.

Halla Tomasdottir (2019) states how there is a crisis of conformity in leadership in the world that must be met with new leadership principles such as sustainability, equality and accountability from courageous yet humble leaders that have a moral compass. The flexible nature required to lead under uncertainty and in a complex environment is clear. In the evolution of leadership theories, Albert King (1990) suggests the ‘new leader’ must be visionary, willing to take risks, highly adaptable to change, willing to delegate authority and place emphasis on innovation. Furthermore, his model holds that a leader must exemplify the values, goals and culture of the organisation and be highly aware of environmental factors. These factors have not changed over the past three decades, adaptability remains prevalent for effective leaders. As described by BRIG Langford (2020), we must be, 'comfortable with change.'

Courage: The leader must demonstrate physical and mental courage to overcome any feelings of discomfort that may impede their ability to command. Demonstrating strength in the face of adversity will generate followership. Importantly, courage will help you maintain high morals and ethics by allowing you to back yourself regardless of position or environment. It also supports the idea of resilience and strength of mind to allow leaders to push their limits.

According to Whitehurst (2018), leadership in hierarchical organisations can focus too heavily on control and compliance. Additionally, he stated that the role of a leader should not be to direct and decide in a volatile and disruptive world but rather to create the context for people to do their best work. We can construct context by creating trust, building relationships, and fostering and motivating teams through the application of these six principles. How you conduct yourself and ultimately who you are as a person will mould you as a leader.