'…As I write this (from the very dusty front seat of a G-Wagon SRV) the digger next to me is an ARA CRV Driver from 1 ARMD REGT, our gunner is a full time scaffolder, part time soldier from 4/19 PWLH, and I’m a former ARA CRV Crew Commander turned ARES Cavalry Scout from 4/19 PWLH. Within the six vehicle SRV Troop and its 18 crewmen, 4 of us are Reservists and are working hand in hand with the Regulars, learning from them and generally becoming mates… It’s an ideal example of how a Light Cavalry asset within an ACR could operate in the future.'

From the notebook of CPL EM Hale, Exercise Predator's Run 2019

Introduction

In this decade, the Royal Australian Armoured Corps (RAAC) is set to introduce a vehicle that will fundamentally change how Australian cavalry operates and has operated in the past. The Boxer Combat Reconnaissance Vehicle (CRV) is a highly capable, adaptable, and an almost revolutionary platform. It is armed with a 30mm auto cannon, anti-tank guided missiles, a 7.62mm coaxial machine gun and a 12.7mm heavy machine gun on a remote weapon system. It weighs over 35,000kg and can accurately hit targets at 4,000m with its main gun. There are also four seats in the back for dismounts. It is a revolutionary progression from the ASLAV CRV and will hurl the RAAC deep into the 21st century.

With the M1A1 Abrams and the Boxer CRV, the RAAC will have two of the best vehicles in the world, and hitting power on a scale unprecedented in our Army. But before the Boxer CRV can be introduced, the ASLAV CRV has reached the end of its service life, and these vehicles are becoming tired. Vehicle numbers are limited by fatigue and the requirement to be spread across the three Armoured Cavalry Regiments (ACRs) and the School of Armour (SOARMD). This gives the RAAC an opportunity to diversify the way Cavalry activities are conducted in the Australian Army. Alongside this opportunity to diversify is the ADFs strategic pivot away from the Middle East and onto our own pacific region. It is a requirement for us to evaluate what vehicles are suitable for these tropical, often jungle environments. While armour can be used with great effect in our region, its challenging terrain is well suited to lighter vehicles that can traverse unsealed roads, use basic or neglected ports or airfields, and cross bridges that are unable to sustain 30 tonne weights. Vehicle portability in the pacific region is a strategic issue.

It is the contention of this paper that to best harness this opportunity and fill this requirement is through adopting light cavalry in the RAAC. The purpose of this paper is to discuss the merits and benefits of this adoption to enhance and compliment the current existing capabilities. Light cavalry can be mounted on a Light Cavalry Patrol Vehicle (LCPV) based on the G-Wagon Surveillance Reconnaissance Vehicle (SRV) and Supacat HMT-E, with Hawkei PMV-L to support and complement. The skillsets already exist, the vehicle platforms are already in service, and the structures can be instituted very quickly with minimal disturbance to the regular and reserve Cavalry regiments. Its introduction would be immediately beneficial in terms of adaptability, flexibility, cost effectiveness, deployability, and capability enhancement. The benefits are immense.

Light Cavalry

From the Employment of Armour doctrine, 'The role and tasks of light cavalry is the same as for cavalry but are enabled through non-AFV platforms. Light cavalry is more likely to conduct security, stability and enabling activities in lower threat environments or in rear echelon areas. Light cavalry operates predominantly mounted in the conduct of their tasks using similar TTP to CRV-based cavalry units and are enabled by a range of protected and unprotected mobility platforms.'

1st Armoured Regiment (1AR) and 2nd Cavalry Regiment (2CAV) have both proved the worth of Light Cavalry/ISR Troops, operating the G-Wagon SRV in 2018, 2019 and 2020. These light cavalry Troops have provided significant capability; conducting typical cavalry tasks but also (perhaps analogous to their Light Horse forebears) able to leave a piquet with the vehicles and dismount when required. They have been impressive in their ability to disproportionately punch above their weight.

The key to their success has been the flexibility and adaptability of their LCPVs. They use speed and manoeuvrability to identify enemy assets and terrain features; low signature to remain below the detection threshold; firepower to extricate or defend themselves and the specialist cavalry crews to push its abilities. The LCPV has been used in a multitude of tasks and can be utilised in place of CRV at times. Whether working as a forward cavalry screen, or as rear area security, the LCPV can allow the CRV Troops to be freed up and more available to commanders. The less technical nature of the vehicle allows reservists to easily integrate and supplement the full-time vehicle crews.

Despite not having classic A-vehicle traits (such as a turret and armour), it still requires unique cavalry skills and for its crew to work as a team. The shared mounted minor tactics work in coordination with the dismounted skills of the existing cavalry scout. Crews morph into cavalry scouts where required, accessing weapons and specialist equipment stowed on the vehicle and moving on foot. This boosts capability of cavalry scouts who can use the vehicles as a launching pad and home base. Despite lacking the intrinsic firepower of an A-vehicle, strong anti-armour capability is available with integral weapons systems that can be carried on the vehicle.

The G-Wagon SRV currently employed by 1AR and 2CAV is capable, adaptable, and most of all, available right now. Regardless of the platform, the capability is what matters. Whether it be an ASLAV, a SRV, HMT-E, bongo bus or bicycle, experience in mounted minor tactics can be shared across the RAAC by both regular and reserve soldiers.

The experience of the British Army and an option for the future in Australia

In 2019 I was fortunate to travel to the UK and conduct a brief study tour of both regular and reserve British Army cavalry units, as well as speak with their soldiers, NCOs, and officers. In the British Army presently, there are six light cavalry regiments: three Yeomanry (reserve) and three full-time. Reserve regiments are paired and linked to a full-time regiment.

Over the past two decades, light cavalry have deployed across the world. They have been able to operate in high and low threat environments and their flexibility is remarkable. This allows them to operate in varied seasons, weather and terrain, which provides options for commanders that would not otherwise be available without a significant logistic trail. In terms of adaptability, light cavalry soldiers can upskill to an A-Vehicle because of their experience and expertise at mounted minor tactics and cavalry fundamentals. There is a strong emphasis on both mounted and dismounted skillsets in the British light cavalry regiments; having their own snipers, anti-tank and dismounted recce assets. The ability to expertly use their 'black Cadillac’s' (boots) is an important one.

In terms of training and trade, the Royal Armoured Corps Employment Schedule (RACES) dictates the courses and qualifications required for its soldiers, with regular and reserve following a shared trade path. RACES ensures interoperability through a common trade structure, allowing not just easy transition between the yeomanry and full-time but a sharing of training and learned knowledge, while maximising the use of resources.

With both regular and reserve light cavalry regiments utilising the Supacat HMT-400 'Jackal' and HMT-600 'Coyote' by mid-2020, there is platform, career and training commonality between regulars and reserves. This allows excellent integration between both, maximising availability in troops and vehicles. The importance of this cannot be overstated. Regular light cavalry regiments can rely not just on its own manning, but also the manning of its paired yeomanry regiment. There is always a significant pool of soldiers able to be utilised.

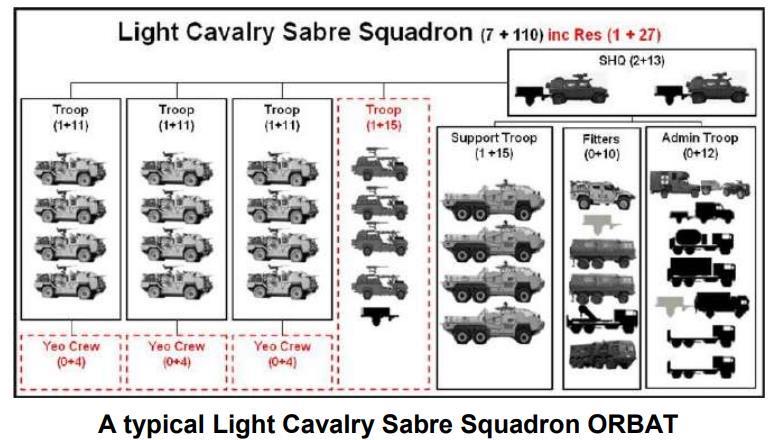

With the full-time, regular army foundation marked in black, the reinforcing/integrated yeomanry is red. Suparcat HMT-400 make up the Line Troop, while the Yeomanry Troop is mounted in Land Rover WMIK (recently replaced by Jackal). Support Troop are mounted in Supacat HMT-600 Coyote and carry additional weapons, stores and equipment.

The benefits of integration and a shared trade structure are easy to identify. It enhances full-time and yeomanry soldiers by lifting the base standards of all in training, learning, working, and deploying together. This can be done in isolation with their own vehicles and crews, before being brought together for combined exercises or deployments. Experience and quality is raised by working together.

Were the Australian Army to apply some of the lessons learned through the British Army light cavalry experience, it could do so through adopting a light cavalry trade structure in the reserve RAAC, but remaining with an armoured cavalry trade in the regular RAAC. These would mirror each other in terms of soldier and officer progression, differing only in vehicle specifics, ie SRV vs CRV. Light Cavalry Squadrons or Troops within the ACR (whether it be a Recon Troop attached to RHQ or a dedicated Squadron, for example), would be primarily crewed by full-time soldiers with a base trade of CRV. This would allow them to seamlessly step between crewing a CRV and a LCPV through their knowledge of mounted minor tactics and cavalry fundamentals. The key to its success would be the ability of the reserve RAAC to round out, reinforce and strengthen the regular RAAC foundation by supplementing crews and supplying their own organic vehicles. Reserve RAAC could train in isolation, but with a common and shared purpose to their full-time counterparts. This would be a collaborative enhancement between reserve and regular capability in the RAAC, where there is currently a sizable gap between the fundamentally different roles of the regular RAAC and the reserve RAAC. The two are currently very separate organisations, wearing the same beret.

The Reserve RAAC

One of the roles of the Army Reserve is 'to deliver specified capability to support and sustain Australian Defence Force preparedness and operations' (2014, Army Modernisation Update, p 43). Additionally, its first core task is to 'deliver specified warfighting capabilities (as the main effort) by raising, training, and sustaining specified ‘round out’ and reinforcement roles' (2014, Army Modernisation Update).

While the relevance and direction of the reserve RAAC is an article in itself, it is perhaps best to quote from the Defence White paper, 2015 regarding their current structure. 'The Defence Reserve Association (DRA) considers that the architects of Plan Beersheba may not have given sufficient thought to how Reserve Armoured Corps (RAAC) units could or should be used in rounding out or supplementing Regular Army Units and capability. For example, Army Reserve RAAC units are tasked with generating a protective mobility capability using the PMV ‘Bushmaster’. These units are not tasked or equipped to undertake a Cavalry role of conducting reconnaissance, defending vital assets, providing convoy protection, staffing listening posts and undertaking surveillance tasks. Consequently, the Army Reserve cannot properly supplement the Regular Army Cavalry capability'.

PMV is not the only task for the reserve RAAC; they are also tasked with creating and sustaining Cavalry Scouts within ECN 063. These are two very separate roles. With providing a PMV lift capability for the Multi Role Combat Brigade (MRCB) and Cavalry Scouts for the ACRs, reserves have no shared vehicle qualifications or expertise in mounted cavalry fundamentals, and are unable to round out and reinforce any regular RAAC roles.

Light Cavalry composition

At 1AR, the light cavalry troop is composed of six SRVs. Much like an ASLAV CRV Troop, this can operate complete or in patrols. It can independently move forward, providing lower signatures and offering stand-off to larger and more valuable CRVs. It can use its crews to conduct dismounted recce, deploy UAV, or remain mounted. It is flexible and adaptable. However utilised, it gives forward eyes to the CRVs and tanks, and allows their commanders a more complete picture of the battlefield. This could create a genuine hunter/killer partnership in the cavalry world.

In a six vehicle Troop, this could be employed as four SRVs, with Troop Headquarters mounted in two Hawkei PMV-L. This offers maximised communications, battlefield tracking and command & control.

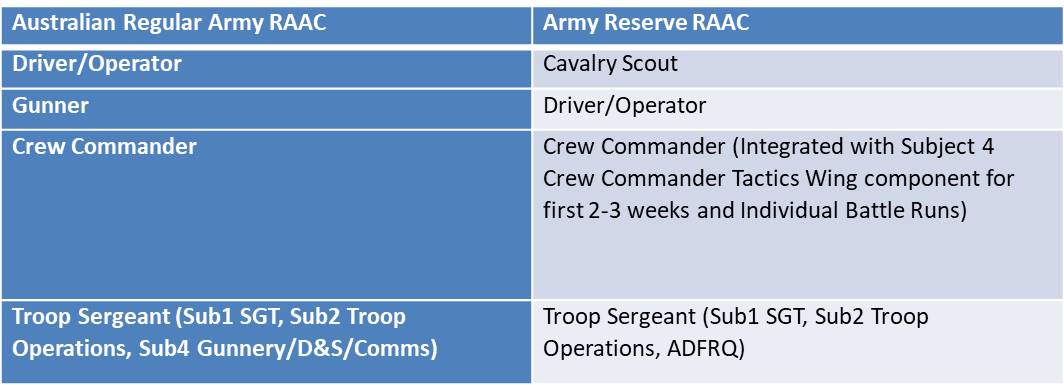

With the light cavalry vehicle composition almost mirroring the established armoured cavalry vehicle composition, a light cavalry trade structure for reservists would follow the structure of the current Regular Army ECN 062 Armoured Cavalry trade structure. Light cavalry reservists would work through a career progression similar to their full-time armoured counterparts, but with additional positions for dismounted capability. This could look like Cavalry Scout/Driver, Gunner/Operator, SRV Crew Commander, and Cavalry Scout Commander. Like the established armoured cavalry construct, within the light cavalry construct would be command roles for Troop Corporals, Troop Sergeants and Troop Leaders. Reserve junior officers and SNCOs would have vehicles and dismounts to command and control. They could gain the experience of managing and leading soldiers and vehicles in the field. This would be an enhancement on the current situation, whereby cavalry scout Troop Sergeants and Troop Leaders have no role within the ACR.

Training can be achieved with minimal disturbance. Driver and gunnery courses can be run at both regular and reserve regiments. Reserve light cavalry crew commanders could be integrated with their full-time counterparts on CRV Subject 4 Corporal at SOARMD and learn part of the same tactics package. This could be, for example, conducting the first 2-3 weeks of that component of the course, up to the Individual Battle Runs. Light Cavalry would advance, contact the enemy, identify, fix and conduct battlefield handover with the CRV who would destroy/neutralise. With light cavalry and armoured cavalry all sharing the knowledge of SOARMD Tactics, Gunnery, Driving & Servicing and Communications Wings, the reserves would harness the experience and knowledge of transitioned full-time soldiers. Hand in hand, reservists transferring to full-time would bring with them experience and knowledge regarding mounted cavalry skills. The Corps would get more competent, experienced, well-trained and cross-trained soldiers with integration between regular and reserve.

While a change to the structure of the RAAC may be imposing, in the long-term light cavalry would save resources and costs by allowing soldiers to train cavalry fundamentals without having to use ASLAV or Boxer. Further, by sharing training and experience between regular and reserve soldiers on a shared light cavalry platform, resources are minimised. Rate of effort is enhanced and more efficient with the ACRs able to conduct fundamental manoeuvre training with LCPV rather than CRVs and with reservists stepping in to fill out incomplete crews. This saves finances through minimising wear and tear to platforms, lowering fuel use by not using CRV, and ensures maximum troops to task. Not only does the RAAC maximise available platforms to train and deploy on, introducing a LCPV would perhaps most importantly unite the RAAC in a shared direction, empowering training reservists in mounted cavalry tactics and theory. All this would be done on a practical platform that value adds to the ACRs and wider Army.

Through shared Cavalry fundamentals of mounted and dismounted tactics and experience, full time soldiers transitioning to the reserve would be able to continue utilising their specialist skill sets. Importantly, with light cavalry being expert in mounted minor tactics and cavalry fundamentals, reservists could quickly upskill onto complex A-vehicles as required. While qualifying a soldier as a CRV Gunner or Driver can be done in a couple of weeks, it takes far longer for them to gain competence and experience in it. With the fundamentals learnt through the use of LCPV, reservists are set up for success, while full-time crews can train mounted minor tactics without causing wear and tear to the CRV fleet.

A common (if not shared) trade structure between armoured cavalry and light cavalry is beneficial to the entire RAAC.

Light cavalry is a capability that can focus on varied threat environments, conventional & unconventional operations in our region, and utilises the best knowledge with the RAAC to do so. Light Cavalry can be deployed quickly, with less resources than its bigger counterparts, and to a hugely wide and varied set of situations.

Experiences in Light Cavalry activities

Throughout 2018 and 2019, reservists from 4/19 PWLH (including myself) have deployed on field exercises with 1AR, acting as cavalry scouts for the CRV Squadrons. On Exercise Predators Run in mid-2019, we arrived expecting to be attached to a CRV Troop and operate from their ASLAVs.

Whilst in the battle group leaguer; however, I was fortunate enough to have a conversation with the Troop Sergeant of the Light Cavalry Troop. He mentioned he was short a crew commander and had several gunner/operator positions unoccupied. With our hierarchy’s approval, my cavalry scouts and I rounded out and reinforced the Troop, filling the vacant positions and enabling an additional full-time soldier to move into a vacant ASLAV gunners seat in another Troop.

Over the next three weeks we conducted straightforward cavalry tasks, but ones ideally suited to a light cavalry asset. The Troop provided rear area security, convoy escorts, and were a vital communication link between elements. We sited hide and replenishment locations; identifying and holding the ground while the echelon moved forward to occupy it. We conducted mounted and dismounted clearance patrols and provided a QRF for the commander as required. We worked hard.

My reservists were embraced by the full-time crews they joined. For these Troopers, ranging in experience from two to four years, it was universally the first time they had properly taken part in mounted cavalry activities. Used to operating dismounted, or sitting in the back of an ASLAV with almost no situational awareness, they now got to observe what a basic snake green, red or amber method of movement looked like, or how bounding overwatch worked, or what a coordinated break from a tree line entailed, or how to hide a vehicle with natural camouflage as part of an anti-armour ambush.

They marked helicopter landing zones, engaged penetrating enemy recon teams, conducted communication relay, and cleared obstacles; they visually saw cavalry operations, and were physically part of it. Their reporting from the gunner/operator position was critical to their crews successes and enhanced everything we did. They were an integral cog in the machine and felt like they were valuable, required, and equal. This invested them in the pursuit of the Troops success. More than anything, they felt like Cavalrymen.

For my part, as an ASLAV, M113AS4 and PMV Commander, I was able to use the training, knowledge, and experience of mounted manoeuvre that I had gained in the Regular Army again. The Army and the RAAC have invested significant time, effort, and resources into making me a cavalry Crew Commander, and I was able to use that investment to enhance the capability of the Troop. It was a good feeling.

I had the opportunity to spend time with full-time professionals, as well as understudy the Troop Sergeant. This sharpened my knowledge in areas, and refreshed it in others. As a reservist, Army is no longer my full-time career and my skills are not as honed as they could be. Integrating the reservists with regulars enabled us to learn from each other and the normal 'cold start' (whereby it can take a few days to switch from civilian brain to army brain) was bypassed. Their army experience and knowledge enhanced ours, while our different life experience widened their perspectives and capabilities. As an example, having a qualified civilian paramedic and nurse was useful when a soldier was injured gathering foliage to camouflage the vehicle. A deep cut to his hand became a learning experience for all, especially for the Combat First Aiders, as the paramedic/reservist treated the wound and took control of the situation with a level of experience typical of an emergency services responder.

By the end of the exercise we returned to 4/19 PWLH as better soldiers, with enhanced or new skills, knowledge and job satisfaction. Our full-time counterparts returned to 1AR having had a rounded-out Troop, more capability through additional soldiers, and exposure to reservists with different life experience. Both developed excellent personal and professional relationships. Whilst part of that light cavalry Troop, every individual was a cavalry soldier first and foremost; they were equal and performing the same role regardless of being Regular Army or Reserve.

Conclusion

The reduced availability of ASLAV and the strategic pivot away from the Middle East to our own region offers the RAAC a great opportunity. This is an opportunity to create more options for commanders within the ACRs, to enhance the ability to conduct cavalry activities, and to provide ways to better utilise cavalry reservists across the RAAC. Light cavalry is a combat multiplier. It was an effective, practical, capable, and cost-effective way in which to increase the ability to conduct cavalry activities into the future. Importantly, it utilises the expert knowledge, experience, and skills of the entire RAAC to do it by harnessing the fundamentals that are unique to cavalry and mounted operations, sharing them across regular and reserve within the corps.

Light cavalry is immensely flexible, and this flexibility is absolutely critical as we face unknown threats in the future. Flexibility allows it to be deployed to a variety of operations, both high and low threat. Whether it be peacekeeping in the pacific region or in a conventional operation alongside CRV and MBT, light cavalry can adapt and provide capability that would not otherwise exist.

Light cavalry in the RAAC gives reservists the opportunity to work alongside their regular counterparts, as well as in isolation towards a common goal and purpose. It gives reserve cavalry a genuinely cavalry role, and a relevance to the RAAC that they arguably have not had since 2006 and the withdrawal of the M113A1.

Adopting light cavalry is a logical and sensible decision for the Australian Army and one that will be greatly beneficial to it.

So is confirming a common vision among all ARES RAAC units which nests clearly with the ARA's requirements of us. Who are we, what do we do, for whom, how do we do it and why?

I believe there are three key (broad) tenets which should guide us in our training and purpose:

1. Remain platform agnostic.

2. Be experts in MMT.

3. Be expert cavalry scouts, proficient in conventional forms of dismounted ISR.

If we can be these things above, then vehicle variants need not cloud discussions - they will come and go. As we have proven, cavalry scouts can also work very effectively when their 'horse' is a CH47.

But good article - well articulated.

Duncan Hains

I have argued previously for vehicles (not necessarily AFVs) which could enable mobile warfare reconnaissance skills to be developed and maintained to be allocated to the RAAC ARES.

As you know it’s the skills that take the time to instil at all levels. Whether or not this is important, depends on the role of the ARES within the ADF. It’s hard to imagine that mobile warfare skills are not required at this time in terms of Defence contingency plans. This is evidenced by the funding granted to procure the Boxer CRV.

BUT … no-one is prepared to state and justify the actual role of the ARES in time of defence emergency. Maybe it’s thought the such a time will not come again. Even the 2020 Defence Reserves Association conference completely side-stepped this fundamental issue.

I hope that the fundamental role of the ARES will be defined, then the wisdom of your proposals will undoubtedly come into play!

I’m looking forward to your next article reflecting on how the training and mindset in the ADF has developed in your time.

Cheers

It was also interesting to read about how easily your reserve and active duty troopers blended together. I've never heard of anything like that in the US Army at the individual crew/section level. Thanks again for this informative read, and I look forward to more great information from you.

I don't think much of the SRVs capabilities, should we be looking to get a more capable platform in the future based off experiences with the current SRV? perhaps closer to the British Supacat?

Where you mentioned the SRV not having A vehicle attributes like Armour and turret, my first thoughts on that has always been sensors and optics of an A vehicle, as the SRV is limited to small arms mounted optics/sensors and the BNVD (while mobile). Do you see the need here to try and offset that deficiency with more extensive drone capabilities and GSR for light cav that can extend the sensory reach or to try and fit AFV like optics (eg telescopic mast mounted FLIR) on the SRV?

And your points on dismounts and mounted was very true, both mobs need to know their skills mounted and dismounted. I disliked once upon a time been told cavalry scouts were no longer an ARA role, so many skills lost from that move.