It comes as a shock to most commanders and military members when they realise Army, and Defence, does not have an injury surveillance system. This article discusses some of the complexities faced in setting up an effective system, why our current systems are not fit for purpose, and potential solutions to the problem.

Defence’s two main forms of data capture for injuries are e-health records (DeHS) and the WH&S reporting system (Sentinel); neither are set up as injury surveillance systems. The World Health Organisation has guidelines on what the minimum data points are for effective injury surveillance, and these guidelines highlight the need for systems to be tailored to specific populations. Even in the sporting world, where injury surveillance has been occurring for decades, there is no consensus as to the best method to collect data to inform injury risk reduction.

The 2019 Productivity Commission (PC) Inquiry into Compensation and Rehabilitation for Veterans found DVA are spending $5.3bn annually on health and wellbeing services. Recommendation 18.1 states DVA should develop outcomes and performance frameworks that provide measures of effectiveness. Arguably for these measures to be truly informative and accurate, the information must be captured from the recruiting stage, through ab-initio training to transition from Defence. If Army and Defence as a whole are going to attribute causation of injuries to time in service we need to capture potential contributing factors during that time. While the focus of this article is physical injuries, mental health can be viewed by the same lens, and there are many overlaps.

PC findings aside, in this digital age we should have access to information that informs decisions on how best to train, preserve and therefore optimise the force.

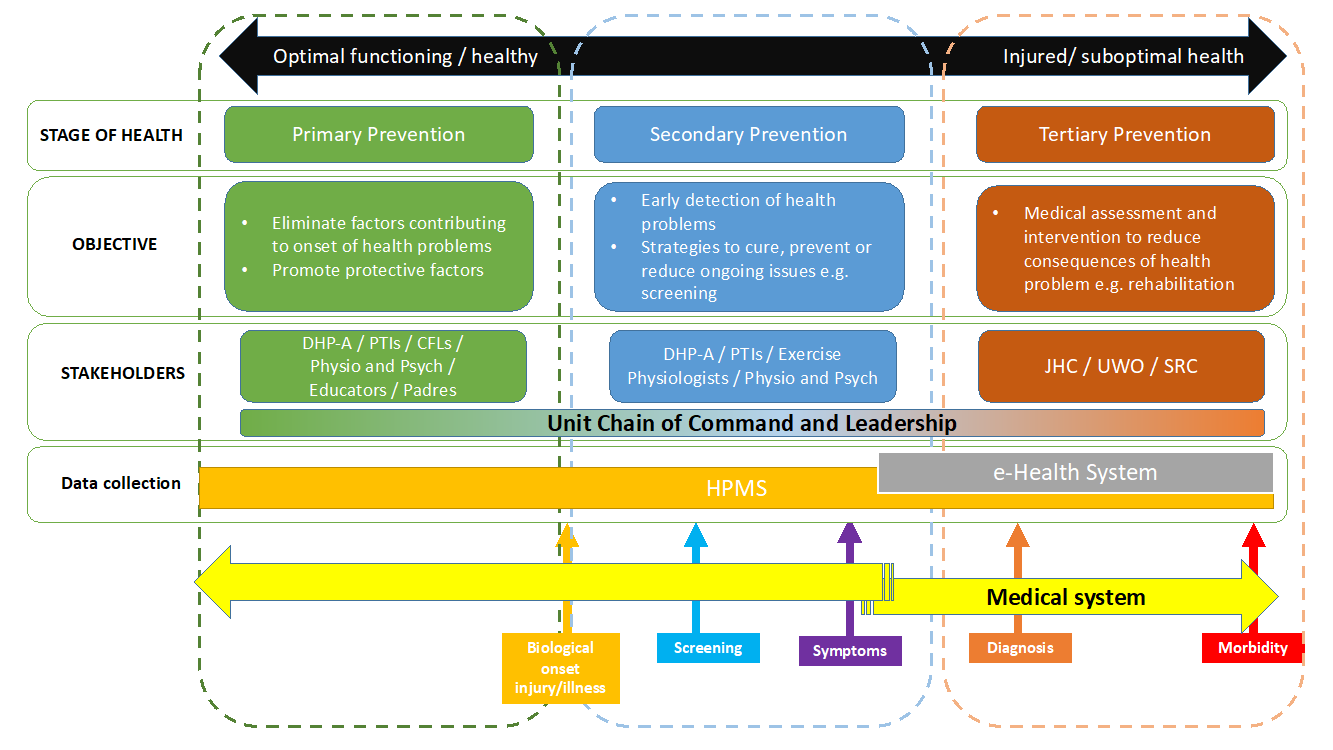

Rather than ‘injury prevention’, the term ‘injury risk reduction’ is more accurate. We must accept it is not possible to prevent all injuries, due to the nature of warfare and how we train for war. However, if we are optimising the force, we need to provide effective injury risk reduction strategies. To reduce injury risk or ‘prevent’ injuries we must first know what we should be preventing. Using a public health approach (Figure 1) our first key question is ‘What is our problem and how big is it?’ The only way to answer this is via surveillance. It is widely accepted that musculoskeletal injuries (MSKI) are the biggest drain on resources in Defence, but the usual marker for MSKI is medical classification, and this does not delineate between mental and physical injuries.

The context and aim of the surveillance and methods of data collection need to be taken into consideration, which is where things get complicated for Defence. The information a commander needs to inform readiness levels, compared with what an epidemiologist or scientist needs to analyse trends is different again to the information useful to Defence and DVA to inform policy. Compounding this, the way the three Services view injury risk reduction differs due to the nature of each service. Definitions of injury and illness need to be agreed on and that is dependent on who is capturing the data, and what it is used for.

Defining Injury – One Piece of the (Surveillance) Puzzle

Three common definitions used in sporting populations are: all complaints, medical attention and time loss[1].

- All Complaints has the potential to capture wider information but logistically, collecting data from large populations is difficult. While each definition has its benefits and constraints, the main take away is that comparison between each data set is not valid and can lead to systematic bias between groups.

- Medical attention will be captured by health professionals, but does not capture overuse injuries effectively. It does not capture the requisite data points for analysis, and also does not address the suspected culture of under-reporting of some injuries.

- Time loss is commonly used in sports as it relates to match time loss. This definition has a poor correlation within Defence. While you could relate a non-deployable MEC J3 to a time loss, the member may be still effective in their work and depends largely on ECN, role and/or Corps. MEC status does not delineate between type of injuries or even between physical and mental health issues, so the usefulness of this data past ready/not ready is limited.

Human Performance Optimisation - ARMY

From an Army Human Performance Optimisation (HPO) perspective, the medical side of injuries is dealt with by JHC, but prevention / risk reduction falls into a pre-clinical area that needs data from the whole population and not just those within the medical system. Health management can be broken down into Primary, Secondary and Tertiary prevention, which provides a useful delineation for ownership of different stages of intervention (Figure 2).

Way Forward

Short term

Using what we have got. Inadequate data capture constraints aside, there is still potential to analyse the information captured within Sentinel and DeHS. We can make informed decisions on how to trial injury risk reduction strategies as long as we understand the limitations of the data, how and who inputs the information, and that these two systems tell us different things.

Improving current systems. While a complete overhaul of the current systems would be required to achieve a true injury surveillance system, we should look to how we can improve DeHS to capture better data points without compromising the health record function. Review and engagement with end users (clinicians and data analysts) should occur to ensure the data captured is able to provide accurate information to commanders.

Human Performance Management System (HPMS). The HPMS is a database that is able to capture training loads, safe start-state testing, self-report measures for musculoskeletal complaints, sleep data and cognitive states. This wealth of information can start to build our knowledge of what risk factors lend themselves to specific injuries. One such tool, Smartabase, has been trialled within 3 BDE and SOCOMD, but to date has been restricted by ICT security issues. Once there are workable solutions, there is potential for an HPMS to begin informing injury risk reduction strategies.

Medium term

Translating research into implementation. While soldiers are not athletes, there are many parallels, and we should leverage off the research that exists within sporting populations, building upon that knowledge, and tailor research specific to our needs. Defence Science and Technology Group also have many studies specific to military populations, the challenge is translating the science into workable initiatives, programs and policy changes that maximise the findings.

Long term

Improved systems and processes. There are a number of projects and initiatives in progress which will contribute to data collection:

- JP2060 – Phase four: Health Knowledge Management should seek to ensure Defence has the ability to capture data that can be utilised for improved surveillance by multiple stakeholders. Whether this nests within the e-health system or is a separate database that has the ability to ‘talk’ to medical, HR and other electronic records, this is integral to Defence addressing a multitude of issues including the health and preservation of its members.

- Joint Transitions Authority (JTA) has been established in response to PC findings. Data is key and finding the most efficient way of collection information in order to inform outcome measures needs to begin at the start and embrace the ‘whole of life’ model.

- The data required for WH&S records differs to health and injury surveillance data; however, there are many overlaps. One system that can be tailored to suit everyone’s needs creates economy of effort in data collection and improves accuracy of reporting.

Conclusion

This is not a new problem. The silo-ed approach to injury reduction taken by WH&S, medical, DVA and human performance is inefficient, but maybe the journey was necessary; as long as we end up with a solution that sees data sharing from all areas.

While this article has focussed solely on injury surveillance, this is only the first piece of the puzzle. The second step of the public health approach model is identifying risk and protective factors, which is an even more complicated topic. The challenge once we have a better injury surveillance system will be accurate analysis of data, then implementing effective strategies to mitigate risks. Once we are able to complete the feedback loop back into surveillance and analysis of those strategies, will we have a better understanding of whether we are achieving injury risk reduction in Defence.

Sentinel is a WHS incident reporting system. Vehicle and other accidents and near misses are included - not just incidents in which a service member is injured. Sentinel is good at recording traumatic incidents - in which an injury or result is immediate, such as a broken arm. However once the incident is logged in Sentinel and the immediate treatment is recorded, the incident (an "event" in Sentinel terminology) is closed and no further information is recorded against that incident. Hence an incident in which a soldier lacerates a hand is recorded - but no information as to how long the soldier is absent from work is recorded, or if an infection results and further time off is required, etc. And Sentinel is particularly poor at recording chronic injuries such as some MSKIs or hearing loss, for example. "Please state the date and time the hearing loss occurred."

On the other hand, DeHS contains a wealth of information, but potentially has too many options. A soldier with an injured knee could be seen by two different MOs who could code the knee injury under two different numbers. DeHS does track treatments, subsequent appointments, and outcomes, but clearly does not track near misses, etc. Unlike Sentinel, it is much more difficult to identify the causative factors behind injuries (or near misses with the potential for injury) on DeHS - eg. a serious of jack failures in the Land 121 vehicle fleet, or a particular action undertaken or location in which injuries have occurred.

In both systems, the analysis to identify commonalities and trends - and therefore to design and implement (and test) interventions is not native - and relies on human identification. While humans are good at this sort of pattern recognition, assistance through good integral analysis tools (and even AI) would go a long way to improving risk recognition and data analysis and would likely result in better outcomes.

The veteran served in the Army Reserve from Feb 2004 until Jul 2007 and then in the Regular Army from Jul 2007 until Aug 2013 and the Army Reserve from Aug 2013 until 2015.

I am hoping someone can advise where Incident Reports are held.