‘Wargaming is a powerful tool. I am convinced that it can deliver better understanding and critical thinking, foresight, genuinely informed decision making and innovation. It allows those involved to experiment and learn from the experiences in a safe to fail environment’.[1]

In late 2017, Headquarters Forces Command hosted a Wargaming Conference with the aim of re-invigorating wargaming as a skill within the Australian Army. The need had been identified in the lessons learned from the HAMEL series over a number of years; the Australian Army was recognising that the wargaming skills of its officers and soldiers had languished in recent years. The Australian Army was not alone in this realisation, in 2014 the United States Department of Defense funded a program to revitalise analytical wargaming through the conduct of tabletop exercises, seminars, workshops and turn based wargames.[2] Additionally, in 2017, the United Kingdom’s Ministry of Defence released the Wargaming Handbook to ‘reinvigorate wargaming in defence’ and to ‘restore it as part of their DNA’.[3]

First and foremost this article aims to stimulate discussion about wargaming, generate new ideas and approaches for wargaming Professional Military Education activities and generally contribute to the reinvigoration of wargaming within Army. More specifically this article will provide readily available and low cost solutions for leaders to incorporate into their unit’s Professional Military Education program. These options include participation in the Army Tactics Competition hosted by the Australian Defence Force Wargaming Association and the establishment of unit ‘Fight Clubs’ leveraging commercially available products (both board games and table top miniature-based wargame systems). While some might consider this a non-traditional approach, others may wonder why these events and clubs have not already been established in units and/or brigades. The implementation of these proposed solutions should be seen as a way of complementing the existing training continuum and a means to enhance Army’s tactical acumen. Additionally; it was to develop the critical thinking capacity of Army’s personnel and provide experiential learning regarding decision making in an adversarial environment.

What is wargaming?

During the opening address of the Forces Command Wargaming Conference Major General Krause, AM (Retd) made the following observation:

‘When you speak to some in this audience and you mention wargaming they will go straight to Course of Action Analysis in the Military Appreciation Process; (Course of Action Analysis) is actually an extremely poor example of doing a wargame’.[4]

With this in mind it is necessary to discuss what wargaming is and its benefits to participants before making an argument that commercial products can be an effective development tool. The origins of military wargaming or Kriegsspiel, can be traced back to the Prussians at the beginning of the 19th century. The Prussians quickly assessed that wargaming improved their officers’ ability to think and act independently.[5]

Widely adopted by militaries around the world, wargaming has highlighted; deficiencies in the United Kingdom’s mobilisation plans prior to the First World War, enabled the development of Germany’s Blitzkrieg doctrine and contributed to the development of the United States Navy’s aircraft carrier based tactics used in the Second World War.[6] Interestingly, despite its ability to enhance military operations there seems to be no commonly accepted definition of wargaming. Four example definitions are listed below:

- Australian Army. A step-by-step process of action, reaction and counteraction for visualising the execution of each friendly course of action in relation to enemy course of action reactions.[7]

- North Atlantic Treaty Organisation. A simulation of a military operation by whatever means using specific rules, data, methods and procedures.[8]

- United Kingdom. A scenario based warfare model in which the outcome and sequence of events affects and is affected by the decisions made by the players.[9]

- United States Army. War-gaming is a disciplined process, with rules and steps that attempt to visualize the flow of the operation, given the force’s strengths and dispositions, the enemy’s capabilities, and possible COAs; the impact and requirements of civilians in the area of operations; and other aspects of the situation.[10]

Despite the variances in the definitions, there are a number of requirements which are consistent throughout; although, some are implied rather than specified, for example; rules, procedures, courses of action, decisions, friendly, opposing and civilian forces. The United Kingdom Ministry of Defence’s Wargaming Handbook (2017) provides an excellent description of what a wargame is:

‘Wargaming is a decision-making technique that provides structured but intellectually liberating safe-to-fail environments to help explore what works (winning / succeeding) and what does not (losing / failing) typically at low cost’. A wargame is a process of adversarial challenge and creativity, delivered in a structured format and usually umpired and adjudicated. Wargames are dynamic events driven by player decision making’. [11]

Based on this description there is no reason why a commercial game cannot be used to support a wargaming professional development opportunity. These games provide the opportunity to exercise tactical decision making against an adaptive, thinking adversary in a safe-to-fail environment. Players have the ability to try multiple approaches to solving the ‘problem’ and can assess the strengths and weaknesses of their plans and reactions to the opponent; additionally, the game can be rapidly reset to provide the opportunity to test alternate ideas. Finally, many of these games revisit historical events and enable an alternative way of observing the associated challenges and lessons learned.

Army’s challenge

The definition above highlights some of the challenges that were identified during the Forces Command Wargaming Conference, namely; that a wargame is a ‘competition between two opposing forces where participants can explore creativity while solving tactical problems and experiencing cognitive stress’.[12] For the Australian Army it has been recognised that ‘teaching wargaming, as a subset of tactics, at the same time that we assess people for suitability for promotion has resulted in Army shying away from the concept of competition’.[13] The challenge that Army has is to find a way to create the 'safe-to-fail' environment which features in the United Kingdom’s definition of wargaming. This should rightly be seen as the critical step to enabling the development of our personnel and their ability to undertake decision making in an adversarial environment. History has shown that wargaming, in a variety of forms, has the ability not only to develop decision making and critical thinking skills, but has demonstrated its ability to positively influence all forms of military operations.

This is not a unique challenge; the United Kingdom and the United States Army have developed their own approaches to provide a safe-to-fail environment that promotes competition. The United Kingdom’s Wargaming Handbook highlights eight case studies of how various forms of wargaming has been used to support the development of their personnel. This includes formal education courses, such as the Royal Marines Advanced Amphibious Warfare Course which wargames the 1982 Falklands War, as well as unit level activities and exercises. The Directorate of Simulation Education at the United States Army Command and General Staff College teaches two elective subjects; the Fundamentals of Wargame Design and History in Action. The directorate also conducts a number of Brown Bag Gaming events for staff and students; these are professional development opportunities that feature a variety of commercial games.

Can ‘gaming’ help?

“All models are wrong, but some are useful” [14]

There are numerous examples of commercial board games being used to complement traditional education techniques. Dr James Sterrett, an instructor at the United States Army Command and General Staff College uses various game systems including; 'Fire in the Lake', 'Napoleon 1806' and 'Strike of the Eagle' in his subjects. Dr James Lacey, an instructor at the United States Marine Corps War College has used commercial games such as Fran Diaz’s 'Polis: Fight for the Hegemony' and GMT’s 'For the People' as well as 'Triumph and Tragedy' as capstone events for various seminars. In his words;

The results were amazing. As every team plotted their strategic “ends,” students soon realized that neither side had the resources — “means” — to do everything they wanted. Strategic decisions quickly became a matter of tradeoffs, as the competitors struggled to find the “ways” to secure sufficient “means” to achieve their objectives (“ends”). For the first time, students were able to examine the strategic options of the Peloponnesian War within the structures that limited the actual participants in that struggle[15].

Regardless of the period that the wargame covers, these games are designed to ensure that the participants constantly face dilemmas. There will never be enough resources or they will face multiple competing priorities, or both, and this results in participants repeatedly engaged in critical thinking. For these two particular courses, the use of commercial wargames ensures the students are constantly engaged ‘as they try to best an enemy as quick thinking and adaptive as they are’[16]. From Dr Sterrett’s perspective, ‘experience is a great teacher and well-designed games can deliver experiences that are tailored to drive home learning’[17].

This is not to say that Army should do away with Staff Rides and Tactical Exercise Without Troops (TEWT) or other similar training activities. Professional Military Education, whether a formal course or a unit level training event, should feature a diverse range of activities and approaches; commercial games are one, albeit neglected by Army to date, of these approaches. These games do have limitations; they can be difficult to learn in a short period of time for an inexperienced training audience, there can be the tendency to fight the game not the scenario and poorly designed games will not generate the desired training outcomes.

Two examples of how Army can rapidly incorporate the use of commercial games and table top wargame systems into its unit-level Professional Military Education program are the Army Tactics Competition hosted by the Australian Defence Force Wargaming Association and the creation of unit-based ‘Fight Clubs’.

Army Tactics Competition

The Australian Defence Force Wargaming Association was invited to participate and address the Forces Command Wargaming Conference; this event served as the catalyst for the establishment of the Army Tactics Competition. This annual event provides the opportunity for Army’s junior leaders to command an Australian Combat Team against a Decisive Action Threat Environment inspired peer or near-peer force in a range of scenarios. The event was successfully piloted in Brisbane in December 2018 and a second event was conducted in December 2019. The Association is currently planning the 2020 Army Tactics Competition for December 2020 in Brisbane; details of the event will be posted via the Association’s website (www.adfwga.com). While events to date have been conducted in Brisbane, this opportunity can be delivered to other locations; however, the requesting unit would need to fund the associated travel.

The Army Tactics Competition is conducted over a three day period and the training audience does not need to have a tabletop wargaming background in order to participate. The event is targeted at junior officers (Lieutenants and Captains) and junior non-commissioned officers (Lance Corporals and Corporals); however, this does not preclude others from being involved. Enabling the conduct of the event are dedicated Opposing Force Commanders which allows each team to face a different adversary in each round and a Blue Force Tactics Advisor; a combat arms corps officer who can assist the Blue Force teams with doctrine and tactics. The competition is held over a three day period; the first day provides training for the Opposing Force Commanders and the Blue Force Advisor and the following two days is the competition itself. Each team completes four scenarios with their performance is graded based on the ability to complete the assigned mission, friendly force losses and other mission specific criteria. The team with the highest overall score at the completion of the rounds is declared the winner. 1st Armoured Regiment won the event in 2018 and the 2/14th Light Horse Regiment are the reigning champions.

The Army Tactics Competition employs a 6mm table top wargame system called ‘Up the Guts’ (UTG) to facilitate this event. The game system provides the participants with the ability to complete all stages of the Military Appreciate Process and then test their selected course of action against an adversary on a three dimensional battlefield. The use of miniatures to represent equipment platforms, units and terrain enables battlefield visualisation but the game mechanic is designed to enable fog of war; units can be hidden unless detected by a unit or dedicated sensor. Combat between units is resolved with dice rolls which serve to capture the chaotic nature of the battlefield.

Units that are interested in participating in the 2020 Army Tactics Competition or learning more about how ‘Up the Guts’ could support their Professional Military Education program should email the Association (adfwga@hotmail.com) or the Army Tactics Competition Event Organiser, Sergeant Ty Casey (tyron.casey@defence.gov.au).

‘Fight Club’

This article has highlighted that the competition element of wargaming is essential to developing the tactical decision making and critical thinking ability of Army’s junior leaders. Yet the training continuum in its current form does not provide a safe-to-fail environment for our personnel to experiment and learn; so how can Army remediate this gap? The formation of unit ‘Fight Clubs’ is a low cost, readily available option that commanders and leaders at all levels can incorporate into their unit Professional Military Education programs. Furthermore, ‘Fight Club’ activities can be stood up at short notice to take advantage of gaps that may appear in a unit’s training program.

What does a ‘Fight Club’ look like? It can be as formal or informal as the commander wishes; it could be as simple as a library of selected board games in the mess / soldier’s clubs, it can be a formal event conducted in a unit facility using digital, analogue or table top games or it could be facilitating the establishment and running of a unit wargaming group. All of these options will foster an environment where wargaming can be embraced as an important skill that all Army’s junior leaders need and highlights that wargaming is more than just 'Course of Action Analysis’. It should also be noted that there are some (formal or informal) wargaming groups that already exist in some of the brigade locations, for example the Gallipoli Barracks Gamers in Brisbane.

What equipment is needed to establish a ‘Fight Club’? A suggested list of commercially available games that could be used to support the operation of a ‘Fight Club’ is listed below. This is not designed to be an exhaustive list but represents many of the games that are currently used to support the History in Action elective class at the United States Army Command and General Staff College. In addition to using a physical copy of a game system, the majority of the games listed below are also available for free via Vassal[18] or other online tools. Although Vassal and other similar systems represents a more complex solution that is reliant on internet access or the establishment of a local area network, it does allow the conduct of remote or distance PME.

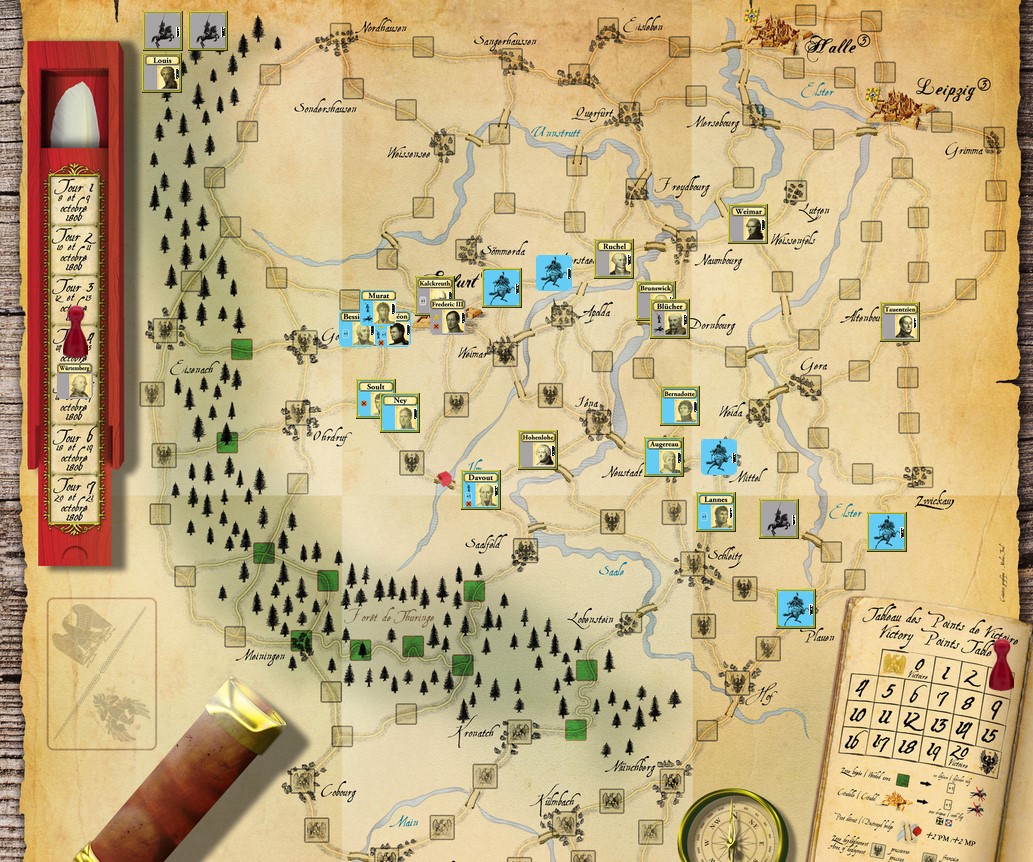

- Napoleon 1806 (Publisher: Shakos). Napoleon 1806 is a two player game which relives the clashes between the Prussian and French forces which culminated in the battles of Auerstaedt and Jena.

- Fire in the Lake (Publisher: GMT Games). Fire in the Lake is the fourth game in GMT’s counter-insurgency game series. Set during the Vietnam War this game features a unique multi-faction system which captures the Diplomatic, Information, Military and Economic elements of this conflict.

- Strike of the Eagle (Academy Games). Strike of the Eagle allows up to four players to revisit the Polish-Soviet War of 1919-1920. The simplified combat system means that the emphasis is on the ability to deduce the enemy’s plans and identifying when and where to employ limited strategic assets.

- Drive on Paris (Publisher: The Gamers). This game is set during the first 100 days of the First World War; with players taking control of French and German forces. Both sides must rapidly attack and defend at the same time without the troops to do both tasks perfectly; resource allocation is critical.

- Triumph and Tragedy (Publisher: GMT Games). Triumph & Tragedy is a geopolitical strategy game for two or three players covering the competition for European supremacy during the period 1936-45 between Capitalism (the West), Communism (the Soviet Union) and Fascism (the Axis). It has diplomatic, economic, technological and military components and can be won by gaining economic hegemony or technological supremacy (A-bomb), or by vanquishing a rival militarily.

- Race to the Rhine (Phalanx Games). Race to the Rhine is set in 1944, Generals Montgomery, Patton and Bradley are advancing their armies across France in order to cross the Rhine River and end the war in Europe by Christmas. Players must manage their fuel, ammunition and rations to enable the advance of their forces but as they advance they can expect to encounter growing German resistance.

Conclusion

As noted at the start of this article, ‘wargaming is a powerful tool’ which can be used to enhance the tactical acumen, decision making and critical thinking skills of Army’s personnel. Within the Australian Army, like many other countries, wargaming has languished for a number of years. Recent initiatives in the United States and United Kingdom have recognised the importance of wargaming and sought to re-invigorate it. Their personnel are provided opportunities to develop through exposure to competition between two opposing sides that are trying to solve tactical or strategic problems within a safe-to-fail environment.

This article has shown that many countries already make use of commercially available products, board and table top miniature games to complement the traditional teaching methods similar to those employed throughout Army’s All-Corps Training Continuum. Additionally, it highlights the opportunities that units can exploit to enhance their Professional Military Education programs and contribute to Army’s re-invigoration of wargaming. These include participation in the Australian Defence Force Wargaming Association’s Army Tactics Competition and the establishment of unit ‘Fight Clubs’. Within these safe-to-fail environments participants will be able to freely explore what works and what doesn’t, while developing their critical thinking and decision making skills. Furthermore, as they react to an opponent that is as quick thinking and adaptive as they are, they will be exposed to cognitive stress; the end result is that all participants will be better prepared for the future operating environment.