If you’re going to discuss your country’s partnerships with Australia, Indonesia, and Japan – or those years when it was filled with soldiers from Australia, or from Indonesia, or from Japan – it might as well be over sushi.

So, sometime between the South Australian kingfish and the zucchini tempura, I asked Timor-Leste's Ambassador what good Australia had done for her country.

Loads of my brothers in arms served on operations such as Op Astute. I was nervous about her answer. Hopefully, it would be something about our forces returning stability her country. Or perhaps an encouraging report about DFAT-backed coffee farming projects led by veterans, such as Orijem Timor.

But to the Ambassador’s mind, the one truly good thing Australia had given Timor-Leste is: ANZAC Day.

Her answer took some digesting. But there was plenty of time. As the fish sashimi kept coming, it became clear Ambassador Almeida cares deeply about national memory.

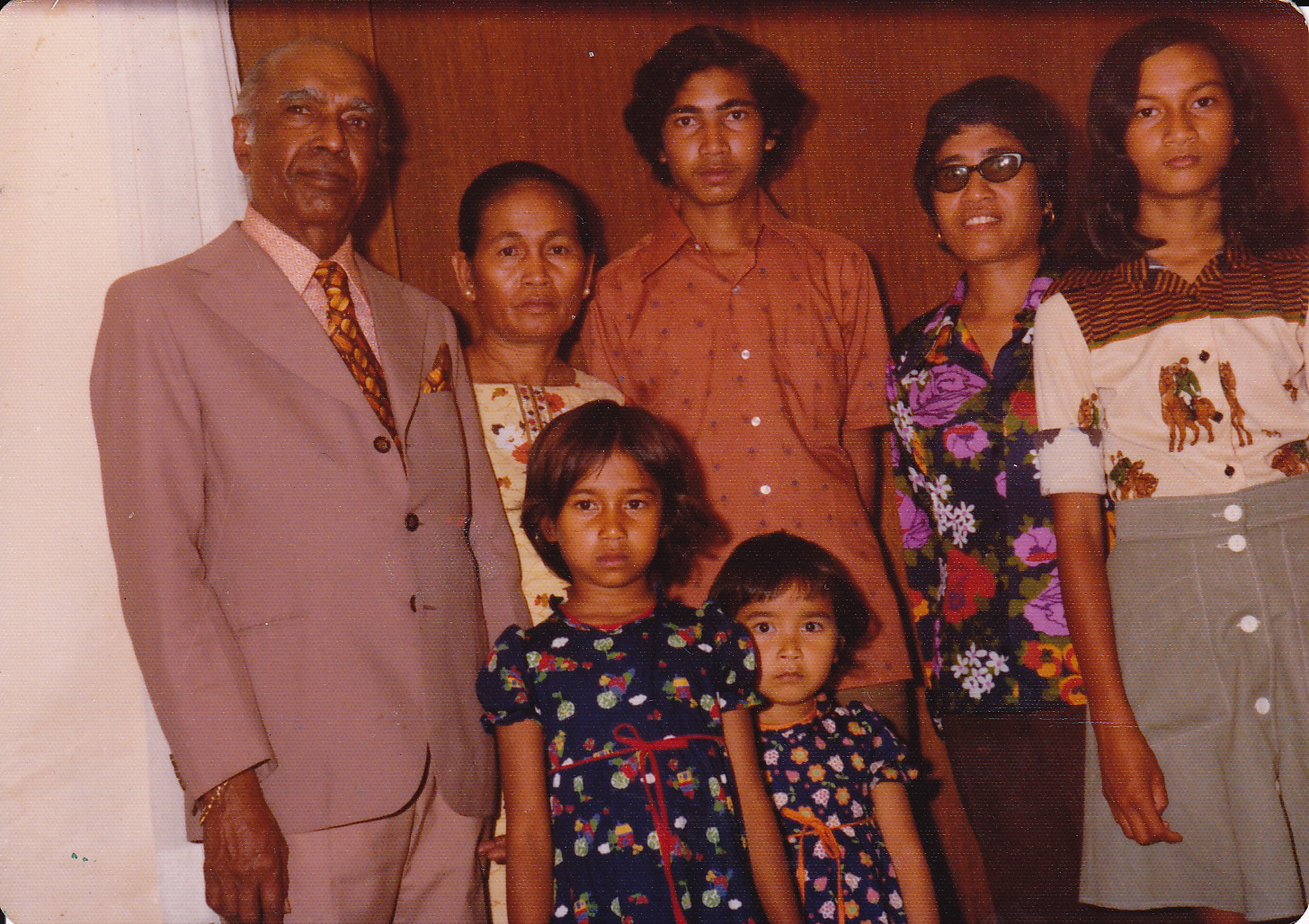

Ambassador Almeida’s father and mother, brother, aunt, herself, younger sister, and niece in Australia 1978.

It is 20 years since the flag-waving street parties in Dili, when Timor-Leste became a sovereign nation. While the country is peaceful and slowly growing today, Her Excellency is worried about amnesia. Not amongst the old, but the young. That they do not know what they have, or how they got it.

“Freedom did not arrive on a tray,” she says. While the Ambassador has a slight stature, when she makes a point, she is forceful. Conviction that comes from personal experience.

When the Ambassador was just 12, Timor-Leste made its first attempt to declare independence. Within weeks, the country descended into a hellish civil war followed by a large-scale invasion by Indonesian forces. It would claim the lives of 200,000 people.

Her mother decided they had to live in a free country, even if it meant being refugees. They arrived in Darwin, but a few months later Cyclone Tracy destroyed that place too. Her older sister selected Sydney as their next home because she wanted to see the Harbour Bridge and Opera House.

Life was good in Australia, but young Ines Almeida felt deeply uncomfortable. When she told people where she was from, she received quizzical looks because it was a country that no longer existed.

Memories of home can be a powerful thing. It drove her into decades of patriotic activism. She joined the Australian-based Diplomatic Front of the East Timorese Resistance. The campaign led by José Ramos-Horta helped create the 1999 Referendum for Independence. While the vote delivered a clear “yes” for independence, it also came with shootings and burnings by pro-Indonesian militias. After its long struggle, sovereignty finally came to Timor-Leste in 2002.

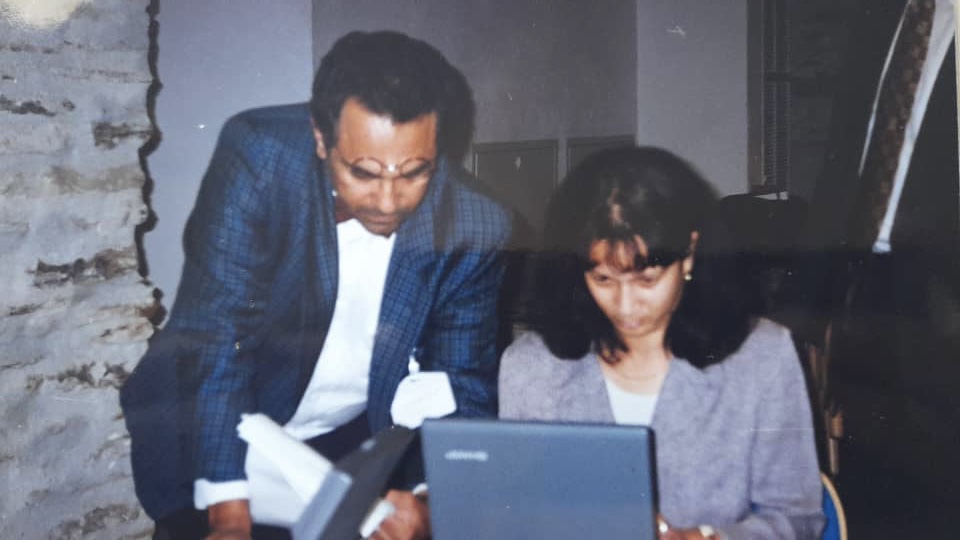

Ambassador Ines Almeida and José Ramos Horta at the UN meeting in Austria 1995.

Ines Almeida was now at home, in her home country. But it was not long before she saw new problems. Veterans from the decades-long war were not integrating. And young people were not valuing the democracy she had struggled to win. That is when she saw Australia had something her country needed.

"You have ANZAC Day. You learn what your forefathers went through. Nothing comes easy. You are democratic. You have your freedom. It came at a cost.”

It certainly does.

With a common desire to keep these memories alive, Australia began hosting Falintil veterans at ANZAC Day marches in 2014. And the people of Timor-Leste have begun their own, very different, commemoration.

Their national day recalls the Phoenix-like events of 3 March 1981. With all other resistance leaders dead, a young Xanana Gusmão gathered the remaining freedom fighters, asking their support to revive a struggle for independence. The third of March is now celebrated as National Veteran’s Day.

The sashimi all but gone, I wanted to move the topic away from memory to my big interest: alliances. But the ambassador returned me to her main course. Memories, it seems, build alliances too.

Ambassador with Double Red Veteran Ian Hampel.

Her case in point is Australia. The partnership between Australia and Timor-Leste does not begin with Australian soldiers helping them in 1999, but with Timorese people helping Australian soldiers fight the forces of Imperial Japan in 1942, a conflict in which 30,000 East Timorese died. One of the famous “Double Red” commandos, who was hidden and helped by the local people, was Ian Hampel. Amongst many tears, he returned to meet his criados, or helpers, at the age of 95.

There’s healing and restoration for diggers who served with INTERFET, UNTAET or on Operations Astute and Tower too. Mick Stone, known as 'The Peacemaker', son of the ADF chaplain Gary Stone, and himself a veteran of Timor, brings Aussie military and police veterans suffering PTSD to Timor to witness these old enemies embracing.

Ambassador Almeida wants to turn our shared history into a legacy. She’s working with the SAS veteran, James McMahon, to develop adventure tourism history along the old WWII tracks – tracks, much like the Kokoda track in Papua New Guinea – to bring new life to the friendship with Australia. It all helps to encourage defence links too.

Australia has committed to developing the Hera Naval Base near Dili on the North Coast. There are plans for a shared port facility near Suai on the South Coast. To go with those Australia will deliver two Guardian Class patrol boats. All moves to help Timor-Leste assert their sovereignty at sea, such as seeing off what she alleges is illegal Chinese fishing, which recently poached 40 tonnes of sharks from their waters.

As we poured out the last of the brown rice tea, I noticed what the Ambassador hadn’t talked about. Nothing about how Australia walked away from the Timorese people in 1975, or letting Indonesia walk in. Not an unkind word to say about Indonesia or Japan whose armies had once brutalised her people. The Ambassador says that grace is driven by memory too.

“We have no enemies. We are friends. We went through 24 years of war. We want to be in peace.”

Peace means remembering the violence and deciding never to return to the cycle of retribution. And so, Timor-Leste began their Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation. A process that invited people to tell the truth about the violent past and apologise, so forgiveness could be offered.

The Ambassador believes nations can forgive each other too. Japan is one of their key aid partners today. Indonesia is a strategic partner. At a veteran's event, old Indonesian fighters came face to face with hardened Falintil fighters, laying wreaths at one another’s cemeteries.

A long peace seems to be settling in.

Ambassador Almeida smiles as she says this. Perhaps because she could see there are some lessons for Australia here. Memories can be a good thing when we deal with them. They can create space for forgiveness. In turn it unifies. They can even bring peace. From there, they can build alliances.

Connecting to memories can be the first step to healing them. Remembering what happened can make forgiveness possible. As the old fighters from both sides of the border have shown, it can even make friendship possible.