As a young Lieutenant, I have seen examples of great leadership and not so great leadership. And I’ve heard countless leadership anecdotes, some of which are helpful.

Army leadership training is excellent because it has to be. Producing well-rounded and values-driven leaders with good character is a fundamental task for Army training centres across Australia. Leaders are a critical capability.

However, university business schools worldwide are experiencing an influx of new leadership style theories and applying these to different workplace situations and industries. It is particularly interesting to apply a seemingly counter-intuitive style of leadership to an industry and see the results.

Let’s consider one of these pairings: servant leadership and the military.

What is servant leadership?

Servant leadership is an emerging style of leadership, coined by Robert K. Greenleaf. Greenleaf wrote:

'The servant-leader is servant first … It begins with the natural feeling that one wants to serve, to serve first. Then conscious choice brings one to aspire to lead. That person is sharply different from one who is leader first, perhaps because of the need to assuage an unusual power drive or to acquire material possessions … The leader-first and the servant-first are two extreme types. Between them there are shadings and blends that are part of the infinite variety of human nature.'

The difference manifests itself in the care taken by the servant-first to make sure that other people’s highest priority needs are being served. The best test, and difficult to administer, is: do those served grow as persons? Do they, while being served, become healthier, wiser, freer, more autonomous, more likely themselves to become servants?'

The Servant as Leader – Robert K Greenleaf (1970)

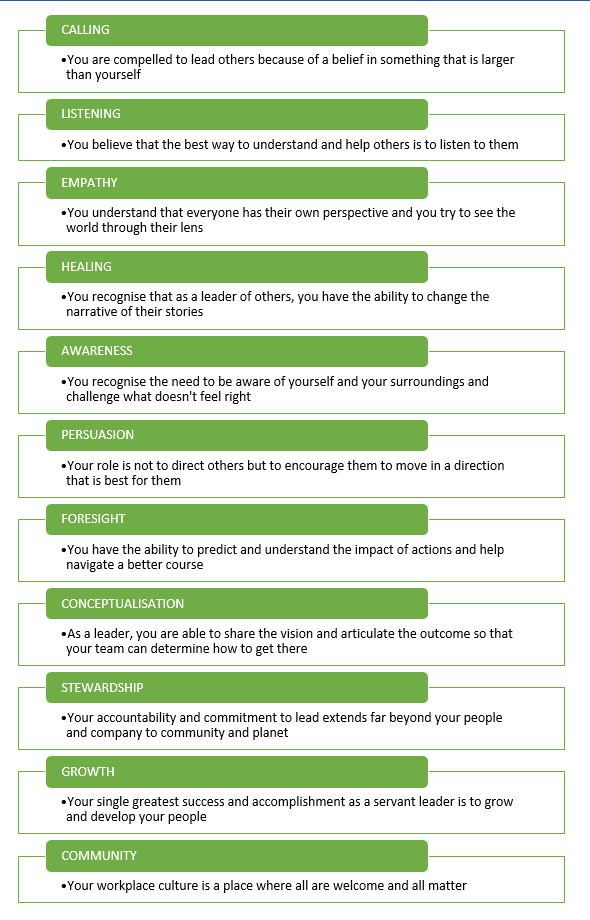

Breaking this down, there are 11 pillars which guide servant leaders:

It is interesting that the underlying premise of servant leadership is to serve considering many people join the Army to serve their country, participating in a shared vision greater than their individual self. Servant leadership and the military suddenly do not seem so incompatible with this observation. But does that willingness to serve leave us when we enter leadership roles in the Army? Is servant leadership incompatible with what the Army teaches?

Can military officers and NCOs be servant leaders?

The Army undertakes a principles-based approach to leadership, coupled with practical experiences cemented at training institutions, such as the Royal Military College. Many people observe that their first exposure to the Australian Army Leadership Principles and their first few years of command experience shape their leadership style over the entirety of their career:

- Be proficient

- Know yourself and seek self-improvement

- Seek and accept responsibility

- Lead by example

- Provide direction

- Know and care for your subordinates

- Develop the potential of your subordinates

- Make sound and timely decisions

- Build the team and challenge its abilities

- Keep your team informed.

Annex B to chapter 1, Land Warfare Doctrine 0-2, Leadership

It is evident that the Army has moved on from a traditional autocratic leadership model towards a modern style of authentic leadership. Authentic leaders broadly adhere to four main principles:

- They are self-aware and genuine

- They are mission-driven and focus on results

- They lead with their heart

- They focus on the long-term picture.

Authentic leadership certainly aligns with Australian Army leadership doctrine and would work very well if you are an ARA officer or NCO. But I argue that adding elements of servant leadership into an authentic leadership style is extremely useful when leading reservists and here are some examples of why.

How can you use servant leadership?

As a reservist, you need to be excellent at balancing the competing priorities in your life and the simplest mantra is ‘family, work, Army’. As a leader of reservists, being a servant leader helps me maintain flexibility in achieving missions and tasks, but also helps me manage the welfare and growth of my people. These are the pillars I will generally add to my style when leading reservists:

Empathy: Reservists are a diverse crowd of people. No two reservists have the same life, civilian work, and Army career experience as each other. When overcoming obstacles to mission success – particularly personal welfare issues – seeing the problem from a perspective other than a ‘green lens’ can be highly effective. Active listening with empathy, taking the time to understand a reservist’s life and family situation and making allowances where possible will earn you the gratitude and trust of your team, and they will be more willing to put the needs of the team above themselves.

Persuasion: It is a fact of life for a leader in the reserve world that you cannot force a reservist soldier to complete a task they don’t want to complete. They will often struggle to make time for the task in the first place (competing priorities!). Direct orders and pressure usually result in silence, so the subtle art of persuasion and soft communication tactics become much more effective. Acknowledging the effort required, clearly communicating the ‘why’ of a task, and taking the extra care to alleviate any barriers to task completion (such as time or civilian work pressures) will improve the effectiveness of your team exponentially.

Stewardship: With one foot in the Army and one foot in the community, reservists are very much tied to the Australian community. There’s an important duality in being a reservist and the strength of this was acknowledged on Operation BUSHFIRE ASSIST. I would argue that a community-focused mindset, paralleled with, 'my mission, my people, myself,' was a competitive advantage in assisting the community to recover from catastrophic bushfires. We were able to tap into the community mindset and respond swiftly and flexibly because we spend so much time in the community itself.

Growth: Growth mentality is arguably more important in a reserve unit. Your soldiers are giving up their Tuesday nights and weekends not only to serve, but also to learn and develop new skills outside their civilian workplace. In a world with so much opportunity, the fact that your soldiers chose the Army Reserve to spend their time and effort is a privilege. Reward your soldiers’ dedication by putting their growth first. Send them every opportunity possible and ask them what kind of training they want. If it can be done, make it happen. If it can’t be done, be clear about why not and, as the servant leader, find alternatives.

Now it’s your turn

While these are the pillars I generally use, you can see that other pillars are also applicable and cross-over with the 10 Army principles. Servant leadership may lend itself well to leadership in the Reserve world, but as with any leadership journey, your style will evolve over time and will be refined according to your experience. But the next time you lead reservists, give servant leadership a try and the results might surprise you.