Background

Over the period of April-May 2019, elements of the 3rd Brigade participated in the US-led Joint Warfighting Assessment (JWA) held in the US. The inclusion of a New Zealand Battlegroup resulted in the formation becoming known as the ANZAC Brigade. JWA tested a Multi-National Division (MND) in a future scenario set in the year 2028. The MND consisted of an ANZAC Brigade, UK Strike Brigade, Canadian Brigade, US Brigade and was primarily supported by US enablers. Importantly, the US Army took the opportunity to experiment with its Multi-Domain Operations (MDO)[1] concept, particularly the Multi-Domain Task Force (MDTF) construct and its ability to operate as part of the Joint Task Force (based on I Corps) to set the conditions for the MND to conduct decisive land-based operations.

The force was pitted against a fictional peer enemy, Katari, who had invaded a neighbouring island not dissimilar to Japan. As the Division manoeuvred and fought its way north it was clear that the Katarian Anti-Access Area-Denial (A2AD)[2] construct was comprehensive, and their ability to contest the Division in every domain[3] was evident. The ANZAC Brigade learnt many lessons as it penetrated and dis-integrated[4] the enemy’s A2AD systems; this paper will reflect on the lessons learnt by ANZAC Brigade Joint Fires and Effects Coordination Centre (JFECC), which was based on 4th Regiment, RAA. Furthermore, this paper is intended to introduce themes to provoke professional discussion and offer solutions where appropriate.

Planning Multi-Domain Effects

The ANZAC Brigade’s approach to MDO was to synchronise lethal and non-lethal effects in time and space in support of the Brigade’s manoeuvre plan. However, as noted by the Brigade Commander on numerous occasions, there were times when we conducted manoeuvre in support of lethal and non-lethal effects. To set the conditions for cross-domain manoeuvre, and achieve a position of relative advantage, it was commonplace that Commanding Officers' (CO) Fireplans included in excess of 20 assets. Traditional capabilities - M777 towed artillery, High Mobility Artillery Rocket System (HIMARS), Close Air Support (CAS) and Rotary Wing (RW) CAS - were integrated with less-traditional effects, such as space, Information Operations (IO) messaging, special forces, maritime forces, electronic warfare, cyber, and sympathetic local militias. The time and effort required to effectively synchronise these assets was considerable, and great care was taken to ensure that the window of their convergence[5] complimented the Brigade’s actions. The ANZAC Brigade was mindful to coordinate its advance, and cue its assets, so that manoeuvre elements remained within range of its lethal effects while ensuring that non-lethal effects were either affecting targets or at the ready; adjacent Brigades were not always so prudent, with catastrophic results.

The majority of exercising organisations followed doctrine/common practice by planning all effects using the 24 hour portions of the 96-hour Air Task Order (ATO) cycle. Using the ATO cycle requires staff to plan against an arbitrary 24 hour period 96 hours in advance; given that operational actions generally spanned more than one 24 hour period they were not viewed as a whole. More importantly, once effects were placed against a 24 hour period they proved unable to be dynamically reapportioned. Due to enemy action, and the resulting alterations to friendly scheme of manoeuvre, the timings for lethal and non-lethal effects were invariably made irrelevant just 24 hours after they had been planned and 72 hours prior to being executed. This required the timings for these effects to be cancelled or redirected and many capabilities placed ‘on-call’ or reinforcing the Brigade with the greatest need at the time. In the case of air apportionment (for which the ATO was designed), many Divisional deliberate targets were planned and apportioned. However, none were struck in accordance with the ATO cycle developed 96 hours out. Rather, all engagements were dynamic and often to exploit time-sensitive opportunities or in self-defence. In short, as soon as the Katarian Forces ‘cast their vote’, planning that had occurred against the ATO cycle was made irrelevant. This lesson was also the case for cyber, Intelligence Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) assets, IO messaging, space and other effects.

Diverging from common practice, the ANZAC Brigade planned and organised lethal and non-lethal effects by operational action; advance, wet-gap crossing, assault, and forward passage of lines. This detailed integration occurred regardless of the length of the action, with some spanning 4 hours and others in excess of 7 days (noting that extensive shaping of subsequent objectives was undertaken). All fire plans were articulated on the Artillery Fire Plan Proforma (WG2), which proved its utility through its ability to simply and effectively detail the intended use of supporting lethal and non-lethal fires. The primary aim of these multi-domain effects was to impose complexity and force dilemma on the enemy through their convergence[6] in the time and space of our choosing. Whilst these requests where submitted in advance with forecast timings, critically all timings could be rapidly recalculated due to being synchronised and recorded against an event and not a time. This approach required a comprehensive handover between fires planning staff and those in current operations, so that the sequencing of effects and how they complement manoeuvre (particularly triggers) were well understood. Planning by operational action allowed us a degree of flexibility and agility through our ability to rapidly re-calculate our requests for resources when timings and available resources changed.

It is strongly recommended that when operating in high-intensity conflict all effects are planned against operational action before being requested through more traditional processes (such as the ATO cycle). This allows for rapid reapportionment when requirements change, ensures that effects remain integrated and synchronised with manoeuvre, and allows higher headquarters the agility to accurately and dynamically prioritise and, if necessary, re-prioritise assets.

Authorities

Whilst JWA lacked the framework and scope to fully test national and multi-national authorities, they were tested to a degree and those that were not were discussed at length by participants. Specifically, the ANZAC Brigade did not exercise requesting sensitive effects through Australian channels, Headquarters Joint Operational Command (HQJOC), Chief of Defence Force (CDF) and further onto Government of Australia (GoAS) for consideration. The ANZAC Brigade did process targets through operational chains, onto the MND and then onto the Joint Task Force (JTF). These authorities were generally only required when we requested assets held at Echelons Above Brigade (EAB) in support of the ANZAC Brigade’s activities.

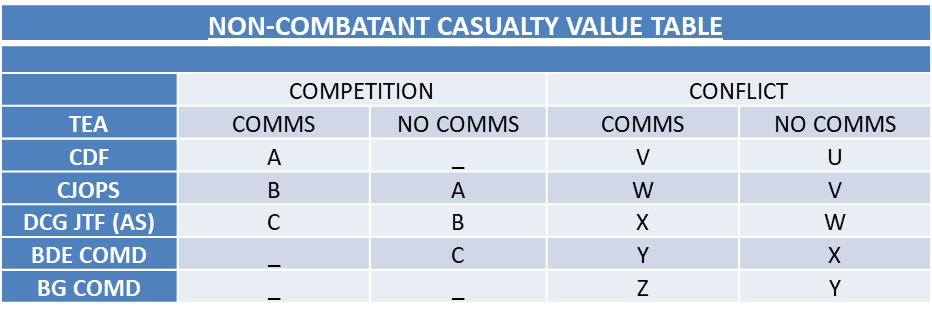

The ANZAC Brigade's JFECC learnt two key lessons in the development of authorities for the operation. Firstly, the requirement to have authorities bestowed considering whether the decision is being made in the competition phase or the conflict phase of the operation. Authorities in the competition phase largely concern non-lethal effects. These are particularly difficult to articulate given the nuanced context and the difficulty of defining likely cumulative and cascading collateral effects. Secondly, consideration must be given as to whether the decision-maker is likely to have communication with their higher level authority. This was particularly relevant to the scenario given communication networks were regularly denied or disrupted, and therefore our ability to communicate with Australia became a friendly targetable critical vulnerability that, if affected at a critical point in a conflict, would create decision paralysis unless relevant authorities are given in advance. A recommended framework to delegate authorities for high-intensity warfighting is at table A.

Targeting

The understanding of the difference between deliberate and dynamic targeting (not to mention engagements in self-defence), and the relevance of tenets such as Collateral Damage Estimation Methodology (CDEM) and Target Engagement Authorities (TEA) in dynamic targeting, developed in exercise participants throughout the activity. The conflation of deliberate and dynamic targeting - and more specifically the use of deliberate targeting principles in dynamic targeting - in recent conflicts (particularly Iraq) necessitated a degree of re-calibration of JFECC and supporting staff at the beginning of the activity. Personnel involved in the application of effects, particularly lethal effects, must ensure that procedures utilised for deliberate targeting are not conflated with the far simpler and more flexible processes used in dynamic targeting, otherwise the complexity of our methods will significantly inhibit our ability to provide relevant and timely fires.

The Six-Step Targeting Process proved a valuable framework for the judicious consideration of targets. Whilst generally applicable, its utility required members of the ANZAC Brigade to understand the nature of the conflict we were fighting and the resultant legal implications. At times it took discipline not to revert to lessons learnt in recent conflicts. For example, whilst positive identification (PID) is a primary consideration when targeting in Afghanistan it is less central to targeting in high-intensity conflict against a state actor. This is for the simple reason that the vast majority of targets are clearly identifiable as enemy due to their dress and equipment. Whilst legal and ethical constraints may necessitate the use of certain targeting procedures in the prosecution of dynamic targets in certain theatres, it must be made clear that they are often not appropriate for high-intensity conflict.

Sensor-to-Shooter links

Given the requirement to integrate effects from all domains, it is evident that our systems and equipment should be sensor-to-shooter agnostic, which is to say that each potential sensor should be able to prosecute targets with each potential shooter. Furthermore, there must be processes in place to facilitate the expedient consideration of these cross-domain requests. For example, while the ANZAC Brigade integrated cyber and space effects into our plan, this was only made possible through extensive face-to-face engagement with US enablers. Importantly, this method of liaison would be impossible to achieve on a realistic (dispersed) battlefield. Whilst difficult enough to achieve with lethal fires in the land-air-sea domains, the problem is compounded when considering the cyber and space domains and the information environment. Adding further complexity is the level of authorities for non-lethal effects, which are often held at JTF, HQJOC and GoAS levels. Additionally, either the sensor or shooter may be a coalition partner or another Department/Agency. This quandary is worthy of detailed consideration, but is beyond the scope of this paper.

Non-lethal Targeting as part of a Division/Corps

Integrating multi-domain effects to gain a position of relative advantage for the ANZAC Brigade required the JFECC to request assets and effects in support of our multi-domain manoeuvre plan. Moving targets vertically (both up and down) through the levels of command proved effective – although challenging at times. The primary challenge in this area was the lack of efficient and proven processes to request uncommon effects, such as cyber, space and some forms of psychological operations (PSYOPS) capabilities. Additionally, there was a lack of understanding of the capabilities amongst staff at all levels. Much of this understanding can be addressed through training; however, some areas are heavily compartmentalised due to security sensitivities. Coordinating and synchronising a large number of lethal and non-lethal effects is challenging enough, but attempting their integration with only a cursory understanding of some capabilities is very difficult. Western forces must address this gap in doctrine, training and classification issues to empower our people to successfully navigate these complexities.

The ability of the ANZAC Brigade to bring non-lethal effects to bear at a time and place of our choosing was further complicated by the difficulties in articulating likely second and third-order effects. There is no endorsed process to inform decision makers, in this case the Commander of the ANZAC Brigade, regarding the legitimate and ethical use of non-lethal effects. When considering targets for lethal strike, Collateral Damage Estimation Methodology (CDEM) provides a scientifically-based method of estimating the likely effects and provides a basis for decision-makers to approve engagements at various levels. Unfortunately, there is no commonly recognised non-lethal equivalent, which makes it difficult to definitively inform decision-makers in their consideration. An example of where this was encountered by the ANZAC Brigade was in the planning of multi-domain effects against a well-prepared Katarian Brigade in a developed urban centre that contained civilians. We planned to periodically employ cyber effects in order to shut down sectors of the power grid to disrupt Katarian operations in the nine days prior to the assault. During the planning process we quickly identified that we did not want to close down power to the hospital. Fortunately, target analysis developed a solution to isolate that sector of the power grid so as not to affect the hospital. The more complex issue was articulating the likely consequence of this attack on other services, such as emergency services, prisons, and port facilities. The ANZAC Brigade utilised a process that was developed within HQJOC in 2015 named the Collateral Effects Estimation Methodology (CEEM). Once complete, the CEEM was passed to Division and, if required, to JTF in order to inform decision-makers as they considered whether or not to allocate the ANZAC Brigade resources. The CEEM provided a valuable framework for the consideration of the known and potential cumulative and cascading effects from the prosecution of targets with non-lethal effects.

Conclusion

JWA ’19 was a fantastic opportunity for the 3rd Brigade Headquarters to undertake high-intensity operations against a near-peer adversary in a Divisional and JTF (Corps) framework. The activity validated many of our TTPs, much of our equipment, and provided mostly positive confirmation of the manner that the Australian Army selects and trains its force. It was clearly evident that to be successful on this type of operation the selection, training and education of teams in the employment of multi-domain capabilities must be normalised. Additionally, successful teams are those that collectively possess a broad range of expertise and are comfortable with ambiguity. The ANZAC Brigade JFECC proved adaptable and professional in navigating a complex activity, despite the paucity of relevant and nuanced doctrine and training. That said, we can, and must, do more.