Note from the Cove Team: This article was written as at 21 Feb 21 and does not consider any significant events post this date. This is a follow up article from Daniel Kirkham. Check out his other articles here:

- Fighting Hybrid Threats: Lessons Learned From DATE

- Army's Hybrid Threat (Part Two): Knowing Your Enemy

‘A nation might profit a lot if the advisory organs of government included an ‘enemy department’, studying the problems of war from the enemy’s point of view - so that… it might succeed in predicting what he was likely to do next’ - B.H. Liddell Hart[1]

Introduction

Australia has recently lacked the imminent threat from a nearby existential enemy pressuring us to agree on a precise unified strategy detailed enough to direct our innovative energies and to guide our day-to-day tactical training as an Army. The risk that this has posed is that of our training becoming focused on achieving vague ‘readiness’ to fight non-defined enemies, as opposed to conditioning ourselves to defeat real threats. Now, the 2020 Defence Strategic Update sharpens the government’s expectation for the ADF to prime itself to prevail in combat of higher intensity, likelihood and at a shorter notice than we have previously been prepared for. Amidst our ‘most consequential strategic realignment since World War 2’, the unprecedented upgrades to our industry, budget, national arsenal and the tightening of our alliances are consistent measures to prevent our operational stagnation. But at the lowest levels, what can we do to prepare our soldiers to ‘shape, deter, respond’? One of the ways we can ready ourselves is by observing what other Armies in the contemporary environment are capable of and using this as a frame for understanding what our Army is capable of and then using realistic training to hone our ability to make the most of what we have. Part 1 of this series defined the DATE hybrid threat and Part 2 discussed how it manifests itself in our training. Part 3 will conclude by exploring options which will not only improve our performance in training, but also help bridge the gap between our strategic guidance and our tactical reality.

Other armies

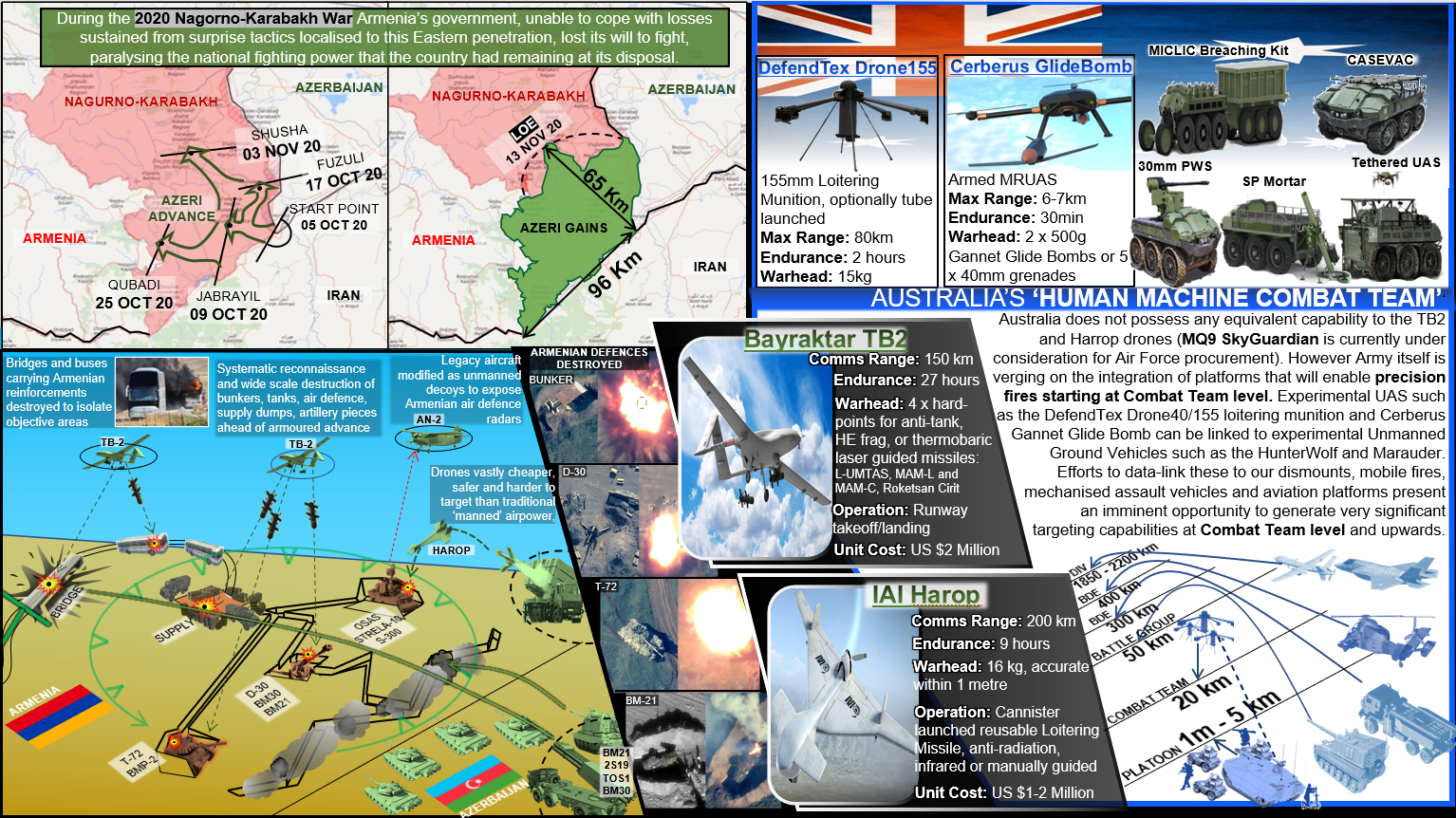

By observing the pattern capabilities developing in the world’s contemporary operating armies, we gain a better understanding of our own strengths and weaknesses. Conflicts such as the recent 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War between Azerbaijan and Armenia is an example. On 27 Sep 2020, Azerbaijan invaded the Armenian controlled region of Nagorno-Karabakh, massing 3 reinforced Army Corps (Division equivalents) in an armoured assault that penetrated Armenia’s defensive line and advancing approximately 80km in 29 days. By the time a ceasefire was agreed upon on 10 Nov 20, Armenia had lost control of half of the region including the capital city, Shusha. Its losses totalled at 287 tanks (70% of Armenia’s tank capability), 69 AFVs, 540 trucks and jeeps, 270 Artillery pieces, 60 AD systems, 22 UAVs and 3,360 personnel casualties. By comparison, Azerbaijan lost only 36 tanks, 14 AFVs (31 trucks and jeeps destroyed or captured), as well as 2,800 personnel casualties. Azerbaijan’s campaign was deemed a success.

At a moderate cost, Azerbaijan reclaimed huge portions of the territory it lost to Armenia in previous conflicts and secured strategic overland borders to its allies, Iran and Turkey. The operation itself is abundant with contemporary examples of proxy warfare, use of special forces, combined arms teams, cyber warfare and INFOWAR. But a primal factor reported as central to Azerbaijan’s strategy was its unexpected integration of armed UAS; particularly the Israeli designed ‘Harop’ Loitering Missile, and the Turkish designed ‘TB-2’ armed drone. These proved equally effective in enabling Azeri offensive manoeuvre and defending against Armenian counter attacks.[2] Though modest by historical standards, a conflict of manoeuvre at this scale, fought by large and well-equipped opponents to a decisively agreed upon conclusion, is an extraordinary occurrence in the 21st century and it deserves admittance into our contemporary discussions about applying force decisively as an Army.

The 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh operation, even with its faults, was still a deliberately planned campaign which ultimately changed the course of history towards Azerbaijan’s ends and is cause enough for us to consider what factors might have contributed to its success. Armenia’s defeat was not due to the size of its military, but in the theory for its employment, which rested on out-of-date tactics and equipment that had not progressed as far as Azerbaijan’s in the intervening years between their last major conflict in 2016. Despite Armenia maintaining a well-trained and similarly sized military to Azerbaijan, the total fighting power of this nation was nullified by their leadership’s loss of will to cope with mechanised manoeuvre, enabled by the surprise use of drone-based airpower. This exemplifies the recurring pattern of institutional shock that follows whenever a new method is exploited against unsuspecting adversaries trapped in obedience to old ways; as occurred with chariots, the stirrup, gunpowder, internal combustion engines and nuclear weapons. We are gradually witnessing the next stage of those aforementioned revolutions in the technology of increasingly AI-enabled robotics. If faced with the threat outlined above, how differently would our Army fair? If we cannot think like our enemies, then our enemies will evolve their tactics in directions we simply lack the creativity to imagine and then they will win. This is only one of many contemporary events now occurring that provides the invaluable frames of reality we need in order to ensure we are not ‘training blind’.

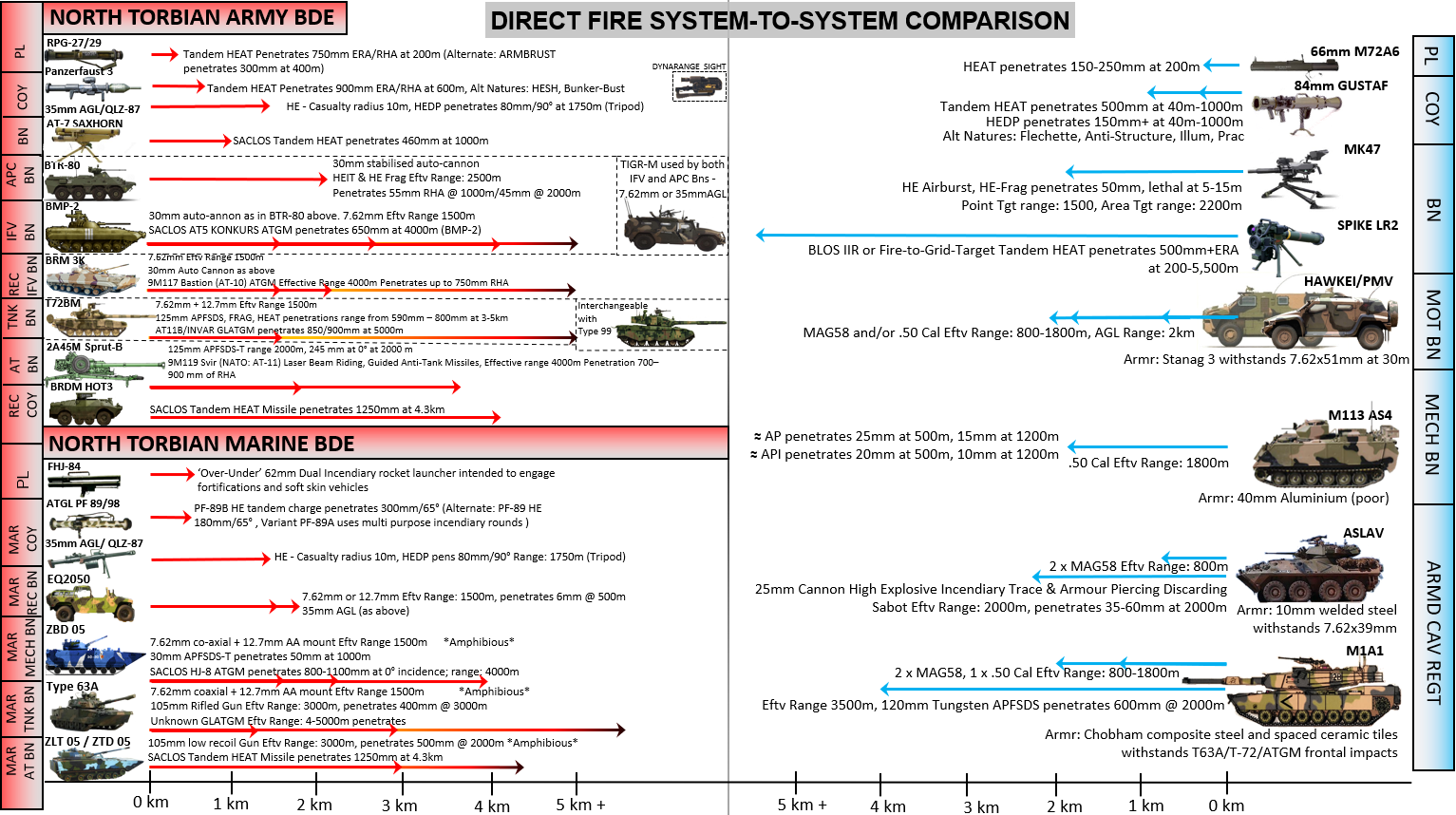

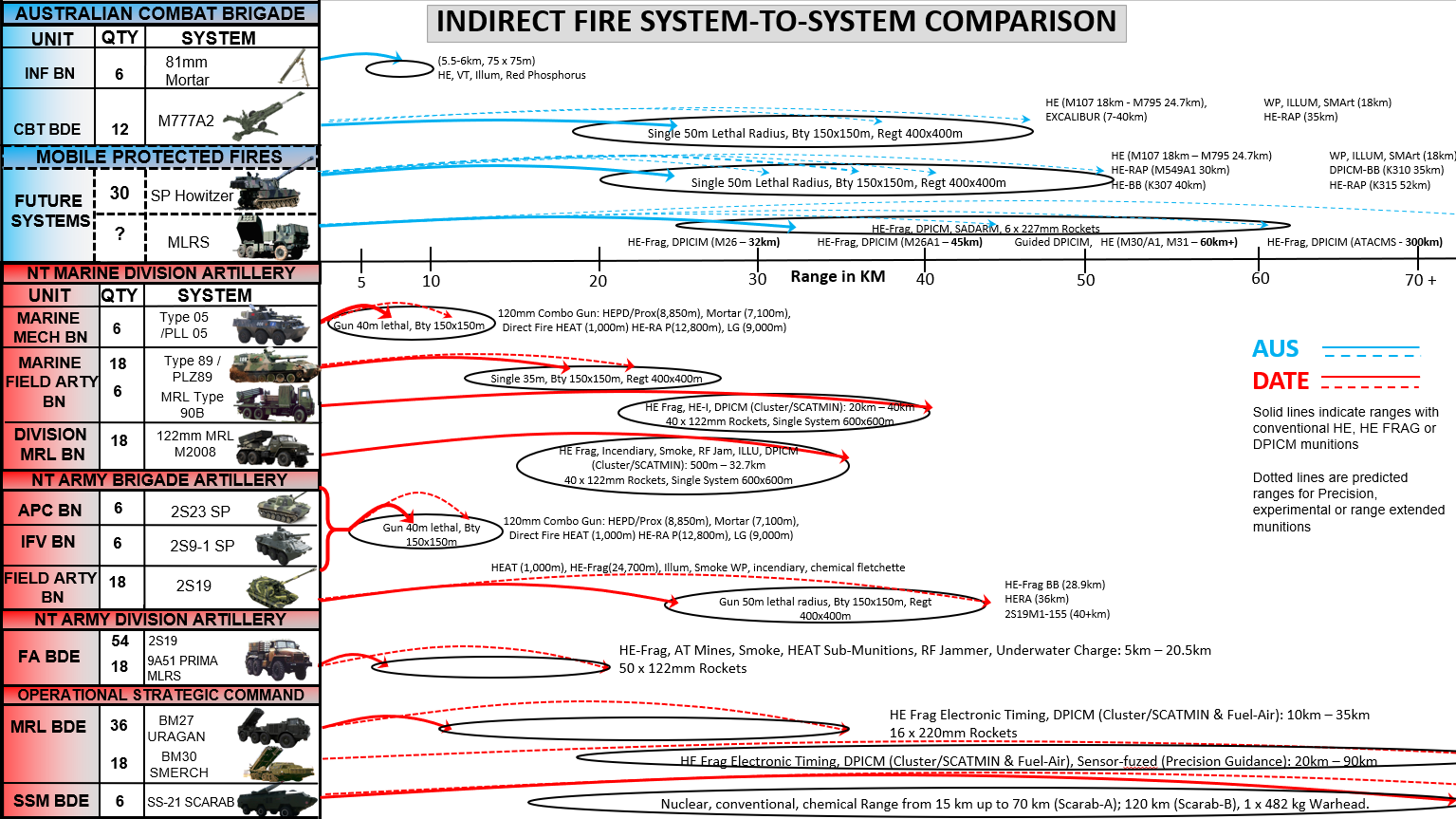

Our Army

Using this frame of reality, we can start to grasp our capabilities relative to the capabilities of our most likely adversaries in the Indo-Pacific. Below is a relative strength comparison of Australian systems aligned to the enemy equivalents, represented by ‘North Torbia’, the DATE-Pacific adversary. One will note our adversary possesses an all-round superior radius of action; greater mobility (amphibious), fire power, range and quantity of systems, with commensurate protection levels. There is a 3:1 overmatch in artillery systems.[3] We see that even at the most basic scale we are rarely able to oppose adversaries frontally, and must achieve dislocation via surprise, concentration and tempo, engaging threats from indirect angles. This may seem like an obvious foundational axiom to many, and yet it is so often absent when we conduct our live training. Whilst we do not want to become trapped in the mindset of trying to ‘defeat equipment’, equipment is an important factor insofar that we understand that our strategic ends are eventually limited by our tactical means; a fact reaffirmed by the asymmetry in capabilities between Armenia and Azerbaijan. This imbalance tells us that it is a good idea to dispense with all latent assumptions of Western technological superiority on the battlefield moving forward, and reaffirms our belief in targeting the human dimension of our adversaries to achieve success using unexpected tactics. The diagrams below may serve as a start-state for all readers to generate more thorough notes of their own, giving them a pre-learning advantage ahead of their next major exercise, training course or real world operation.

Note 1. Near-future Australian and adversary systems (Boxer, Lynx/Redback) are absent. These are not expected to reach FoC until year 2026 and 2030 respectively.

Note 2. Critical enemy enabling capabilities are omitted; Attack aviation (MI35 HIND E), UAS (ASN-207, S100, Skylark II), and air defence systems (SA-18 MANPAD, PGZ07, HQ16, HQ-17), Electronic Warfare, Engineer and Chemical Warfare systems.

Honing what we have

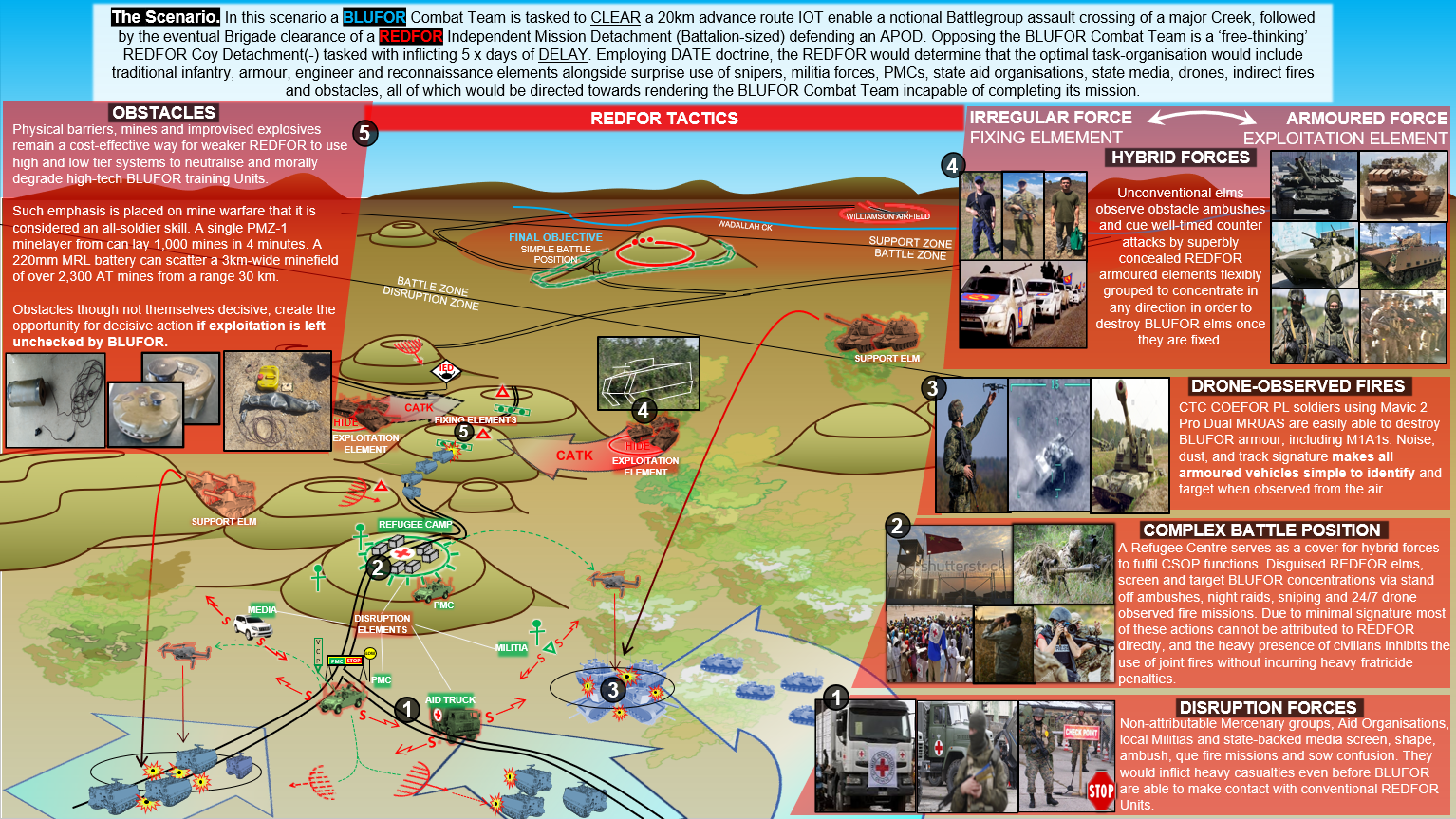

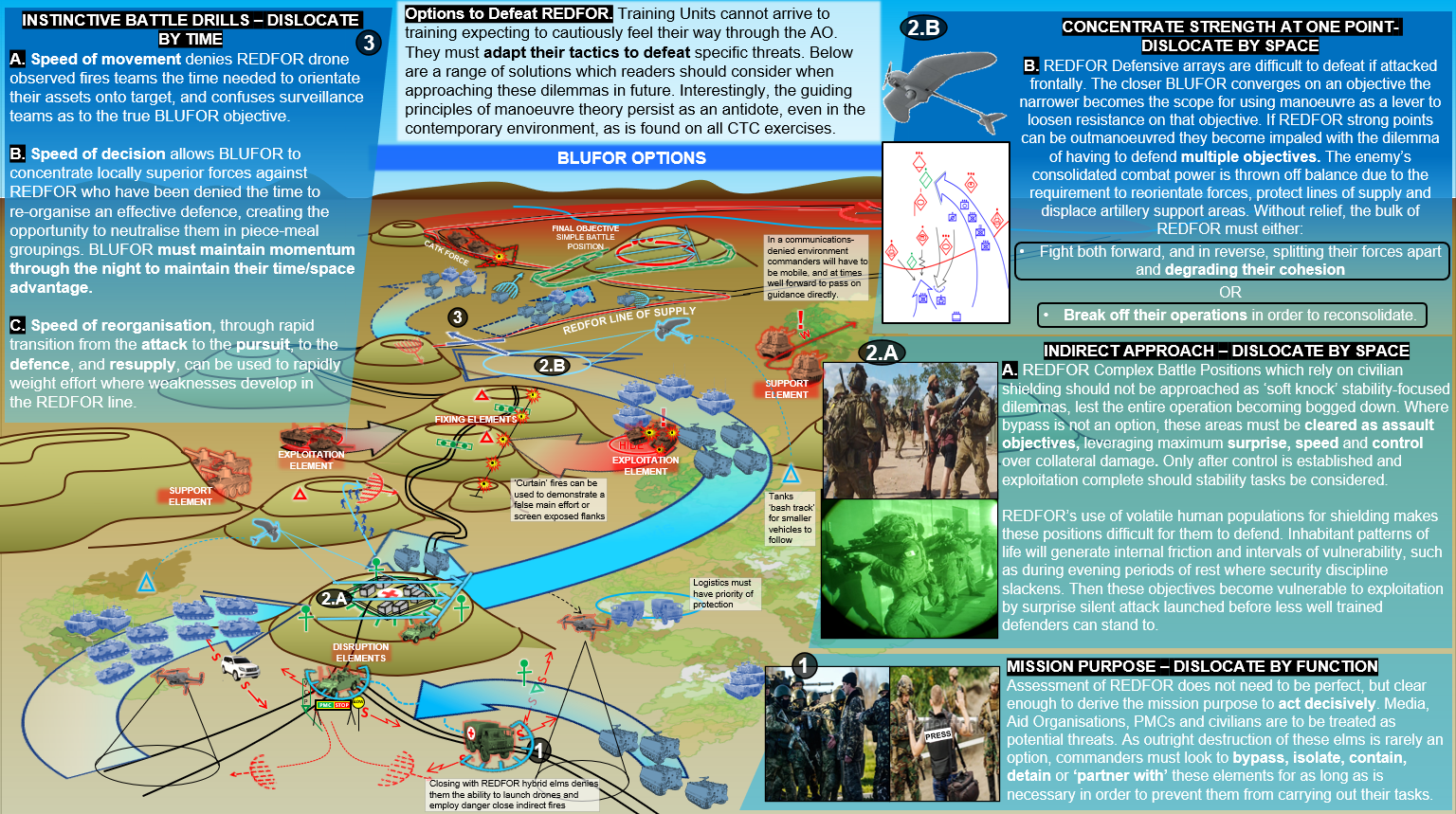

We need not limit ourselves to tabulated theory when we can execute live plans against our enemies in simulated training environments. In the absence of war, high pressure scenario training that affords units the opportunity to freely explore creative tactical solutions for modern enemies is the core of the Combat Training Centre's (CTC) mission. With CTC’s full implementation of DATE into all of its Warfighter exercises, BLUFOR training units who fail to offset the above adversary strengths in firepower, range, mobility and creativity and will experience a sharp increase in difficulty against REDFOR operating in line with contemporary operating environments. The training unit who possess the least understanding of these environments, and the least appreciation for the lengths the adversary will go to kill them, will repeatedly find themselves shocked at the losses they sustain in training against free-thinking enemies using hybrid warfare, electronic warfare, mixed tier systems, drones, artillery, obstacles and IEDs in training. The image below depicts an example of the type of DATE scenario that CTC has used to train Combat Teams. Decide how you would defeat the dilemmas posed by REDFOR below, and you will unlock for yourself an advantage in the next exercise or real world operation you undertake.

Why bother? - History repeats itself

What relevance do these training dilemmas have to Australia’s strategic position in the Indo-Pacific? As a country that relies on import-export trade to generate 43% of our GDP and over 50% of our liquid fuel needs, Australia is critically vulnerable to denial of its sea and air links.[4] Our military power rests on our economic endurance as much as a battle between armies. The last time these links were threatened directly, in 1941, we were not ready despite having already been at war against Germany for two years. The Empire of Japan had left the US Pacific Fleet in a row of burning hulks in Pearl Harbour and conquered almost the whole of Western Pacific and South-east Asia to carry forth its zone of strategic control to the Northern approaches of Australia. [5] 20,746 Australians alone died in captivity.[6] Now it is interesting to note the extent to which strategic confrontation of this sort is becoming increasing reality once again, though this time through use of pre-emptive hybrid, or ‘grey zone’, operations which form a cornerstone of DATE tactics.

China’s establishment of a global belt and road logistic system for projecting economic and military power has once again become the focal point of Australian media reporting when in December 2020, the construction of a joint Chinese-PNG ‘fishing industrial park’ in the nearby region of Daru, only 200kms from Australia’s coast, was announced. [7] Concern over the intentions of the action, setting aside the ecological and economic factors, stems from the established role that China’s fishing fleet plays as a para-military arm of the PLA’s Naval forces, so often associated with being an instrument of antagonism, territorial expansion and a precursor to escalation on the grounds of ‘security’.

At first glance, the security of Australia’s far reaching sea and air links appears to be a Navy and Airforce-centric dilemma. However, when contextualised to our environment, we see that a full quarter of world trade, including Australia’s, passes through the vital Lombok, Sunda and Malacca Straits (Indonesia and Malaysia), and we start to appreciate that these narrow waterways are a mere 20-24km wide at their thinnest points; well within the influence of ground force effects in a joint context.[8] We also see that the growing tactic for asserting strategic control over contested areas is shifting towards the deployment of land-based populations in the phenomenon of the expanding archipelagic city. ‘Floating cities’ such as China’s Shusa City are currently being built atop the artificial islands straddling the contested Spratly and Paracel regions as a means of expanding government controlled areas outward, adding a powerful land power dimension to what is traditionally a far-off naval and air dominated domain.[9]

Historically, deploying well forward alongside partner nations to counter threats afar is one of our founding traits as an Army. On 25 April 1918, our Army learned of its importance in ensuring the success or failure of such a strategy after our failure to seize the decisive terrain of the Third Ridge and Sari Bari Heights at Gallipoli; which remained only lightly defended by a Turkish screen line. Within six hours, our decision not to exploit our initial success was turned against us by the outnumbered Turkish defenders who gallantly mounted a costly Regiment-sized counter attack that would ultimately contain the 1st Australian Division to a defensive posture where it would remain until the campaign’s costly defeat.[10] From this we can learn just as much about the potential for localised initiative exercised by land-based defenders to carry decisive strategic consequences, even against far greater reaching strategic opponents. If this is a mode of fighting we wish to return to, then understanding our past environments and enemies is just as useful as understanding those of our present.

Conclusion

Today, our current and near-future operating environment continues to manifest itself in immensely powerful ways that threaten to wrest the initiative from us if we are blind to their developments. The reverberations of events that have occurred afar, and the proximity of events growing nearer to us are signalling the danger of our becoming stagnant; the core of our ‘Army in Motion’ concept. The consequences of the 2020 Defence Strategic Update needs to reach down to the individual level so that our teams understand they do not have to wait for a declaration of war in order to get specific about conditioning themselves to the elements that will make up our most likely future conflicts. We can do this by investing in our understanding of our contemporary environment as a whole, understanding our capabilities relative to our threats, and by using our training as a tool to ensure we can generate credible force capable of defeating a threat; even if our equipment is overmatched. This is the challenge posed by CTC, who will continue using DATE to ‘operationalise’ environments and enemies that elevate the collective standard expected of all of Army’s Combat Teams to perform under realistic conditions. Far from being alarmist, by increasing our readiness to defeat contemporary systems and tactics, we decrease the chances of war actually occurring.

‘It is not the big armies that win battles, it is the good ones’ - Maurice De Saxe[11]

Australia is a *maritime* continent-nation.

Armenia and Azerbaijan are virtually landlocked nations Caspian not withstanding, engaged in a mountain warfare.

The "North Torbian" state has no prospect of success in conducting an invasion of Australia employing conventional doctrine and forces.

So what lessons for the Australian Army?

The Liddell Hart quote was most apt.

And, although history does repeat itself, there was no history of a Chinese offensive in the South-West Pacific, though there was a Mongol one to Java.

That is to say the ADF has no precedent to rely on in military history.

Now to capabilities.

There had been several examples of strategic warfare in the region to Australia's North.

All such examples involved one of two approached: wide-ranging harassment of trade shipping (piracy) and seizing islands as bases for local area dominance.

The later came in two 'flavours' during the Pacific War: the USMC frontal assault of prepared fortified islands, and the US Army's less bloody advance the Australian Army participated in.

The point being made here is that there is a rarely stated principle of war that no war has ever been won without a capability for the offensive.

That is, the ADF must have strategic capability to conduct a distributed archipelagic offensive operation to defend Australia.

Such an operation cannot be conduct by the RAN or the RAAF, but is only possible for the Army.

Does the Army have this capability?

None, 0, nil, nada, naught.

The Army boasts 25 operating heavy tanks that cannot be landed on a beach in anything but dead calm and no resistance.

There are also ASLAVS never designed for amphibious operations, the 1960s 'buckets', and towed artillery. PMVs don't count because they are not 8x8s capable of negotiating archipelagic littoral terrains, though I will be told I'm wrong on this.

All of these depend on nine century old LCM-8 designs to get ashore in sea state 3/4.

The Army is busy buying the largest 'reconnaissance' vehicles in the World, and looking to replace above-mentioned 'buckets' with vehicles designed for the Fulda Gap of the Cold War rather than maritime littorals.

Australia's 'amphibious' capability is represented by three rifle companies of the 2RAR in rubber boats.

Ostensibly there are three battalions of SOF, but there are not three units capable of deploying even one into combat without impinging on the needs of the 1 Division, which in any case had never to my knowledge exercised in conducting strategic manoeuvre with all three brigades, likely a fiscal decision.

That is, the Australian Army has no doctrine, experience or equipment to conduct offensive operations in its own regional environment, either to achieve operational reach, or tactical entry.

If exploring the Conventional Operating Environment Force means defending Cairns, Australia has already lost the war.

If COEFOR means exploring warfare in the maritime littoral, the Army is yet to begin thinking.

Truth comes in a bitter pill.