Melee warfare, by its nature, demands that adversaries close the distance to engage in close-quarters hand-to-hand (H2H) combat. This form of combat is inherently lethal, often resulting in life-threatening injuries caused by stabbing, slicing, or blunt force trauma at close range.[1] The unrestrained brutality of H2H can evoke scenes reminiscent of pre-gunpowder medieval warfare, where knives, swords, clubs, axes, spears, and improvised weapons necessitated a visceral physical and emotional commitment to the battle space.[2]

Recent reports from high-intensity conflicts, including the Falklands (1982), Iraq (2003–2019), Afghanistan (2001-2021), Ukraine (2022–ongoing), and Gaza (2023–2025) indicate that, under certain situational conditions, the likelihood of H2H engagement increases.

It is important to clarify that this article does not cover combative self-defence. Instead, it looks at melee as a tactical use of lethal force, examining the physiological and psychological demands needed for success. While melee might seem simple, its ethical complexity arises when we face the dehumanising aspects of such encounters.

As Captain William Fairbairn observed in 1942: ‘In war you cannot afford the luxury of squeamishness. Either you kill or capture, or you will be captured or killed. We’ve got to be tough to win, and we’ve got to be tougher and more ruthless than our enemies.’[3] This mindset remains relevant in modern warfare.

Therefore, this article aims to examine the situational factors that may lead to the resurgence of melee combat. Using open-source reports and firsthand accounts from soldiers involved in recent engagements, it seeks to identify the tactical conditions where H2H combat has taken place.

Modern Melee Firsthand Accounts

H2H combat usually occurs in stronghold settings where tight terrain makes enemies fight at very close range. These situations often require weapons and tactics similar to those used in earlier fighting periods. Such engagements require a level of aggression that many western forces find ethically and psychologically difficult to accept.

For instance, during house-clearing operations in Fallujah, Iraq, US Marine Corporal Sean Stokes killed an insurgent with a trench knife fitted with brass knuckles, later questioning whether its use breached the Geneva Conventions, highlighting the moral tension involved in close-quarters lethality.

Open-source accounts vividly demonstrate the brutality of such encounters. Again in Fallujah (2004), US Army Staff Sergeant David Bellavia, running low on ammunition, resorted to improvised weapons, including a rifle butt, helmet, and body armour plates, before fighting the enemy with his bare hands. The fight escalated to eye gouging and ended with a knife kill.[4][5] Similarly, Colour Sergeant Brian Wood, MC described a bayonet charge in Al Amara after insurgents ambushed his unit from fortified trenches.[6] The experience echoed the Falklands War, where Major Kiszely’s bayonet snapped while engaging the enemy in close combat during an assault at Mount Tumbledown, underscoring the raw intensity of H2H combat.[7]

Recent conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza have seen a resurgence of H2H combat. In Bakhmut, Ukrainian soldier Dmytro Vatagin described the fighting as ‘bare-knuckle fist fighting’. While British intelligence reports indicate that Russian troops have used entrenching tools as bludgeoning weapons during ammunition shortages. Footage supports their use in confined corridors where firearms were not engaged due to prevailing circumstances.[9][10]

In Gaza, Israel Defence Forces Rear Admiral Daniel Hagari confirmed H2H engagements but withheld details due to their sensitive nature.[11] In 2020, one of the most unusual modern examples occurred: Chinese and Indian troops clashed in the Galwan Valley using rocks and clubs because of Rules of Engagement (ROE) restrictions on the use of force. This resulted in dozens of fatalities and highlighted the brutal intensity of combat under strict engagement rules.[12][13]

H2H combat remains a brutal constant in modern warfare, emerging when terrain, tactics, or rules reduce engagement distance. Its resurgence highlights enduring human vulnerability, moral ambiguity, and the primal realities of lethality in confined, high-stakes environments.

Melee Warfare Situational Factors

In modern warfare, there is a perception that H2H combat has become increasingly uncommon due to the dominance of advanced weaponry and the widespread use of firearms. The integration of small drones and other high-tech surveillance systems has further improved early threat detection, allowing soldiers to seemingly keep their distance and avoid close-quarters fighting.

However, all technologies are vulnerable to malfunction and only enjoy temporary tactical superiority before countermeasures reduce their effectiveness. This was highlighted at the Eurosatory Defense Show in Paris (19 June 2024), where French Army Chief of Staff General Pierre Schill said, ‘The advantage now enjoyed by small aerial drones on battlefields including in Ukraine is but a moment in history... Already today, 75% of drones on the battlefield in Ukraine are lost to electronic warfare.’[14]

While some may argue that melee combat is outdated or ethically unviable in modern conflict, evidence suggests otherwise. A US Army combat survey (2004-2008) from Iraq revealed that 19% of soldiers reported using H2H skills during engagements. Though a minority, this figure provides insight into the nature of close-quarters encounters:

- 72.6% employed grappling and wrestling techniques

- 21.9% used improvised or available weapons, and

- 5.5% relied on body weapon strikes, primarily elbows and knees.[15]

While the Jensen survey highlighted the types of techniques used, it did not examine the tactical circumstances surrounding these encounters. Broader reports suggest that H2H combat often occurs under specific conditions, such as munitions shortages during stronghold attacks, surprise close-range encounters, and operations within confined battle spaces. The use of melee weapons like bayonets, clubs, entrenching tools, and knives was – in some cases – actively encouraged by commanders.[9][10][16][17]

Many combatants had received prior training in melee techniques through military combatives programs or martial arts. Overall, H2H combat seems most likely in complex, narrow environments that restrict team support and heighten the chance of surprise. When combined with the pressure of reloading primary firearms under stress, these conditions can lead to close-quarters engagement despite technological advances.[18]

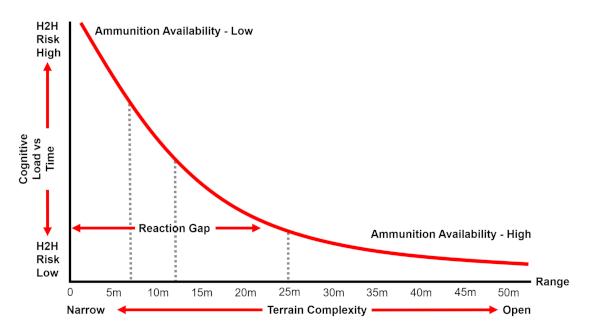

From a tactical perspective, H2H combat is inefficient in terms of time, skill application, and risk to team cohesion. The physiological and psychological shift into a ‘reptilian’ survival state can impair recovery, particularly in cognitive and executive functioning.[19],[20] As shown in the diagram below, four key situational elements consistently emerge across H2H engagements:

Confined or Narrow Battlespace. Trench and urban warfare, as seen in Ukraine, significantly restrict movement and complicate manoeuvre. Urban terrain features dense structures, narrow streets, and civilian presence – creating ethical dilemmas and requiring strict ROE adherence.[21] Combat in this environment often overlaps with humanitarian tasks, demanding high physical, cognitive, and emotional resilience due to proximity to threat actors.[22] In contrast, trench warfare involves brutal engagements within five metres, necessitating direct entry, refined small-unit tactics, and adaptation to fortified, irregular layouts.[23] Zigzagged trenches disrupt command and control, fragment teams, and increase the risk of H2H proximity.

Firearm Stoppages. Firearm stoppages, though rare, still pose a tactical risk. The EF88 Assault Rifle has been extensively tested to fire high volumes with minimal malfunctions.[24] Comparable systems like the M4 carbine exhibit a 1% failure rate [25], while the upgraded SA80 L85A2 achieves 99.8% reliability.[26] Therefore, operational readiness relies on user skill and environment adaptation. In Close Quarter Combat (CQC), any interruption to a weapon’s cycle creates a critical vulnerability. While stoppage clearance times differ among weapon systems, once an adversary is within striking distance, trying to fix a malfunction is seldom feasible until the threat is neutralised or subdued.

Ammunition Shortages. Battlefield logistics are often compromised by both direct and indirect attacks on supply lines. These disruptions are increasingly carried out by military forces supported by civilian networks using affordable tools such as Uncrewed Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) or small aerial drones and mobile apps to report enemy positions.[27][28] This agility allows for targeted interference with munitions and essential equipment during assaults, while also raising ambush risks and restricting mobility.[29] In trench and urban warfare, resupply frequently requires manual transport to frontline positions, adding extra strain and danger for troops. When resupply fails, forces may turn to rationing and alternative tactics, including melee combat.

Ambush and the Element of Surprise. Surprise acts as a key trigger for H2H combat, prompting closer examination of human reaction time under cognitive load. Cognitive load reflects the mental effort needed for adaptive decision-making, influenced by task complexity, threat dynamics, and schema development, as well as stressors like fatigue, anxiety, or distraction.[30][31] When faced with increased time pressure, cognitive demand rises, often heightening excitatory responses while reducing brain inhibitory control, which can impair situational awareness in CQC, especially regarding distance, threat speed, and rapid responses.[32]

For example, a policing study on the validity of the Tueller Drill (which suggests that a threat actor can cover 6.4 metres in 1.5 seconds) indicated that, at best, officers under stress averaged 1.43 seconds to draw their pistol and fire. Despite this, officers often failed to respond before contact occurred, suggesting that a safer engagement distance may be closer to 9.75 metres. Alternatively, movement tactics, particularly sidestepping or 45-degree lateral shifts, significantly reduced risk, highlighting the limitations of static postures in dynamic threat environments.[33] However, as previously noted, the restricted and narrow nature of the battlespace is likely to hinder effective use of movement and distance-based tactics.

Figure 1. Melee Warfare Situational Factors.

Melee Risk Mitigation Measures

Pre-mission combative training is most effective when tailored to expected melee demands, using routine drills and realistic scenarios to engage the perception-action loop and promote adaptable performance. Its main goal is to develop or improve autonomic nervous system responses, especially sympathetic activation, by better controlling heart rate, lactate, and cortisol levels under stress.

This enhances recovery, composure, and operational efficiency. Building on this foundation, Low-Fidelity Simulation (LFS) and High-Fidelity Simulation (HFS) offer structured ways to boost autonomic and cognitive adaptations through targeted, high-intensity reflex training that mirrors the pressures of CQC.

Low-Fidelity Simulation (LFS). Combative reflex training (sparring) should involve short bursts of high-intensity effort, mainly engaging aerobic systems while incorporating grappling, striking, and simulated weapons to mimic CQC. This method improves physiological, cognitive, and neuromuscular readiness. Weekly reflex-based sessions have been associated with increased brain caudate volume [34], showing neuroplastic adaptation from repeated motor-cognitive demands. Reflex training is best integrated into competitive microcycles or tactical training routines. Brain stress markers induced under LFS tend to return to normal within 48 hours [35], indicating low neurophysiological strain and a strong preparatory advantage. This neuroplastic adaptation provides the foundation for understanding how individual traits and physiological factors affect combative effectiveness, as seen in martial arts competitions.

Martial arts competitions serve as a potential platform for designing LFS activities. These competitions highlight melee advantages influenced by technique, body mass, reach, and sex-based physiological traits. For example, lighter athletes (≤56 kg) often excel in striking due to speed and agility, while heavier athletes (≥85 kg) tend to dominate in takedowns and ground control, thanks to greater upper body strength and reach.[36][37]

The competition induces stress levels that activate autonomic and hormonal systems, leading to sex-specific survival behaviours.[38] The neck, a primary target in melee combat, requires careful training to account for its anatomical vulnerability. Therefore, combat sports offer an ideal platform for LFS by helping soldiers shift their focus from discomfort to tactical decision-making. They foster mindfulness, emotional regulation, and resilience through cognitive reappraisal, while varied rules simulate different ROE and stress adaptation demands.[39]

This physiological and psychological conditioning through combat sports complements the Army Combative Program (ACP) weapons training, which similarly demands reflexive control, strategic tool selection, and composure under combat stress. Weapons training prioritises recovery and retention of primary weapon systems under close combat stress. Soldiers progress through primary, secondary, tertiary, improvised tools, and body weapons to enhance survivability, motor proficiency, and injury awareness. Regular firearms practice is essential for developing reflexive control, postural balance, and quick tool selection aligned with threat levels in CQC. Training should advance from individual to team-based approaches and drills.[40][41]

High-Fidelity Simulation (HFS). HFS delivers immersive, live-action scenarios that boost both individual and team performance. It imposes greater cognitive demands, cuts tolerance for mistakes, and enhances realism by integrating blank or man-marking munitions, pyrotechnics, olfactory cues, and combat noise simulation. This level of fidelity reflects operational conditions and allows for real-time measurement of stress responses and performance metrics, making it perfect for advanced continuation training and operational readiness testing. To fully simulate operational stress and improve training results, HFS must activate the full range of human senses through intentional multisensory stimulation.

Human sensory systems respond to chemical, thermal, mechanical, and light stimuli, enabling perception through sight, smell, hearing, taste, and touch. HFS should incorporate multisensory equipment such as simulated munitions, pyrotechnics, props, lighting, noise, and smell stimuli to induce stress responses and promote neuroplasticity. Real firearms with non-lethal munitions and realistic role players (active/passive) further improve training realism. Equipment selection should aim to create sensory overload or deprivation to test performance under pressure. Proper PPE and scenario relevance are vital to ensure safety and support cognitive-behavioural learning outcomes.[47]

HFS Simulation Metrics. Biochemical sampling provides valuable insights for research and targeted stress response validation but is generally impractical for large-scale soldier training due to its complexity and resource demands. While useful for confirming physiological states, it lacks the immediacy required for real-time instructional feedback. In contrast, HFS in medical and first responder training increasingly uses wearable biofeedback devices as a scalable telemetry solution for monitoring physiological responses. Metrics such as heart rate, respiration, electrodermal activity, temperature, gaze, and facial muscle activation are continuously captured via sensor systems. This data, collected during HFS scenarios, supports dynamic assessment of cognitive load when combined with a self-appraisal tool such as the NASA-Task Load Index scores,[43] task-specific checklists, and bio-signal trends; enabling responsive, performance-driven feedback.

Building on this, video-based observation in HFS environments enhances coaching and instruction by utilising metrics such as temporal consistency (decision flow and timing), dynamic degree (movement intensity and stress response), and factual consistency (alignment with doctrine and realism).[44][45] Advances in machine learning and virtual reality facilitate real-time skill assessment through behavioural biometrics including gait, gesture, spatial motion, and language use. Next-generation VR-HFS systems also integrate multimodal bio signals, such as electroencephalography, electrocardiography, gaze tracking, and gait changes, creating sensor-rich ecosystems for scalable and adaptive training.[46] As a result, HFS is most effective when implemented as part of a multimodal framework and requires clearly defined performance expectations before being incorporated into conventional military training programs.

Conclusion

In modern warfare, melee combat remains a raw and ethically challenging aspect, emerging in specific tactical situations where distance breaks down and lethality is immediate. Despite technological progress in weapons, surveillance, and long-range engagement, recent conflicts from Fallujah to Bakhmut show that H2H combat still occurs in confined, high-pressure settings. Terrain restrictions, ammunition shortages, weapon jams, and unexpected encounters continue to lead to close-quarters fighting, requiring physical resilience and mental readiness beyond standard training.

To mitigate these risks, tailored pre-mission combat conditioning and simulation-based training are essential. LFS enhances reflexive control and neuroplasticity through martial arts and competitive drills, while HFS replicates operational stress using multisensory immersion and real-time performance metrics. Wearable biosensors and video-based observation improve feedback via telemetry and behavioural analysis, enabling dynamic assessment of cognitive load, stress response, and tactical decision-making. Emerging technologies like virtual reality and multimodal biometrics (EEG, ECG, gaze, gait) provide scalable, adaptive solutions for performance tracking and real-time feedback. However, HFS is most effective when implemented within a multimodal framework, with clearly defined performance expectations and integration into doctrinal training pipelines, making it potentially too complex for large-scale military application.

Ultimately, the resurgence of melee combat highlights the lasting human aspect of warfare, where survival depends not only on tools and tactics but also on the ability to control fear, act decisively, and adapt under extreme pressure. Preparing soldiers for this reality requires a mix of physiological conditioning, mental resilience, and ethically grounded training specifically tailored to the brutal demands of CQC lethality.

End Notes

[1] L. Gershon, ‘Mass Graves of 13th Century Crusaders Reveal Brutality of Medieval Warfare’, Smithsonian Magazine, 20 September 2021, <https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/mass-graves-of-13th-century-c…; [accessed 10 November 2025].

[2] H. Strachan, The British Army, Manpower and Society into the Twenty-First Century (London: Routledge, 2021) <https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/edit/10.4324/9781315039657/british-…; [accessed 10 November 2025].

[3] W.E. Fairbairn, GET TOUGH! How To Win In Hand To Hand Fighting (The Naval & Military Press Ltd, 2017), preface V.

[4] J. Clark, ‘5 Harrowing Stories of Hand-To-Hand Combat in Iraq and Afghanistan’, Task & Purpose, 9 March 2017, <https://taskandpurpose.com/history/5-harrowing-stories-hand-hand-combat…; (accessed 10 November 2025).

[5] Video Blogger, ‘Savage Hand-To-Hand Combat, Fallujah’, Military.com, 21 March 2011, https://www.military.com/video/operations-and-strategy/iraqi-war/savage… (accessed 10 November 2025).

[6] C. Wyatt, ‘UK Combat Operations End in Iraq’, BBC News, 28 April 2009, <http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/8016685.stm>.

[7] Johnboyzzz, ‘Battle of Mount Tumbledown 13th June 1982’, ARRSE website, 13 June 2011, <https://www.arrse.co.uk/community/threads/battle-of-mount-tumbledown-13…; (accessed 10 November 2025).

[8] J. Haltiwanger, ‘The battle for Bakhmut is getting so close that “fistfights have been happening”’, Business Insider Africa, 7 March 2023, <https://africa.businessinsider.com/military-and-defense/the-battle-for-…; (accessed 12 November 2025).

[9] M. Kuepper, ‘Russian troops are forced to use SHOVELS during hand-to-hand combat in Ukraine due to a shortage of ammunition as Putin continues to lose his grip on the war’, Daily Mail, 6 March 2023, <https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-11824349/amp/Russian-troops-fo…; (accessed 10 November 2025).

[10] T. Watling and M. Parry, ‘Russian troops forced to fight with “shovels” in “brutal” close-combat fight’, Express, 6 March 2023, <https://www.express.co.uk/news/world/1742464/Ukraine-war-British-Challe…; (accessed 10 November 2025).

[11] E. Fabian, ‘IDF says troops facing complex close quarter combat in Gaza’, Times of Israel, 31 October 2023, <https://www.timesofisrael.com/liveblog_entry/idf-says-troops-facing-com…; (accessed 10 November 2025).

[12] BBC, ‘India-China clash: 20 Indian Troops killed in Ladakh fighting’, BBC News, 17 June 2020, <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-53061476>.

[13] India Today Web Desk, ‘China Suffered 43 Casualties during face-off with India in Ladakh: Report’, India Today, 16 June 2020, <https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/india-china-face-off-ladakh-lac-c…; (accessed 10 November 2025).

[14] R. Ruitenberg, ‘Small drones will soon lose combat advantage, French Army chief says’, Defence News, 20 June 2024, <https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2024/06/19/small-drones-will-…; [accessed 10 November 2025].

[15] P.R. Jensen, ‘Hand to Hand Combat and the Use of Combative Skills: An Analysis of the United States Army Post Combat Surveys from 2004–2008’, United States Military Academy, 19 November 2014, p. 3.

[16] J. Perreira, ‘Bayonet Fighting: All of the Gen’, Forces Net, 9 February 2021, <https://www.forces.net/feature/bayonet-fighting-all-gen> [accessed 10 November 2025].

[17] A. Brar, ‘Video Surfaces of China and India Fighting With Sticks and Stones at Border’, Newsweek, 11 June 2024, <https://www.newsweek.com/china-india-clash-video-nuclear-weapons-geopol…; [accessed 10 November 2025].

[18] P.R. Jensen, ‘“It was fight or flight...and flight was not an option”: An Existential Phenomenological Investigation of Military Service Members’ Experience of Hand-to-Hand Combat’, PhD diss., University of Tennessee, May 2012, p. 77, <https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/1310>.

[19] R. Carter, S. Aldridge, M. Page and S. Parker, The Human Brain Book: An Illustrated Guide to Its Structure, Function and Disorders (London: DK Publishing, 2019), p. 48.

[20] NeuroLaunch Editorial Team, ‘Fight or Flight Response: The Reptilian Brain’s Survival Mechanism’, NeuroLaunch, 30 September 2024, <https://neurolaunch.com/fight-or-flight-reptilian-brain/> [accessed 10 November 2025].

[21] J.J. Medby and R.W. Glenn, ‘Challenges Posed by Urbanized Terrain’, in Street Smart: Intelligence Preparation of the Battlefield for Urban Operations, 1st edn (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2002), pp. 25–38, <http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7249/mr1287a.11> [accessed 10 November 2025].

[22] S. Plapinger, ‘Urban Combat Is Changing: The Ukraine War Shows How’, Defense One, 3 February 2023, <https://www.defenseone.com/ideas/2023/02/ukraine-war-shows-how-urban-co…;.

[23] J. Schogol, ‘Trench warfare tips: What US troops need to know from Ukraine’, Task & Purpose, 23 November 2023, <https://taskandpurpose.com/news/us-military-ukraine-trench-warfare/>.

[24] N.R. Jenzen-Jones, ‘Testing & Evaluating the EF88 Assault Rifle’, Small Arms Defense Journal, 11 August 2023, V5N1, <https://sadefensejournal.com/testing-evaluating-the-ef88-assault-rifle/…;.

[25] P. Boyce, ‘Army tests carbines for the third time in extreme dust’, U.S. Army, 17 December 2007, <https://www.army.mil/article/6627/army_tests_carbines_for_the_third_tim…;.

[26] A.G. Williams, SA80: Mistake or Maligned – And What Next?, 7th revn, April 2013, <https://web.archive.org/web/20221123175126/https://www.quarryhs.co.uk/S…;.

[27] L. Collins and J. Spencer, ‘Urban Warfare Project Case Study #12: Battle of Kyiv’, Modern War Institute, 21 February 2025, <https://mwi.westpoint.edu/urban-warfare-project-case-study-12-battle-of…;.

[28] K. Tebbe, R. Pommeranz and G. Scholl, ‘From An Engineering Perspective: Small Drones Affecting The Course Of Warfare’, The Defense Horizon Journal, 3 July 2025, <https://tdhj.org/blog/post/small-drones-warfare/>.

[29] V. Mittal, ‘Russia And Ukraine Are Focusing Attacks On Each Other’s Supply Lines’, Forbes, 7 August 2024, <https://www.forbes.com/sites/vikrammittal/2024/08/07/russia-and-ukraine…;.

[30] Sweller J. Cognitive load theory, learning difficulty, and instructional design. Learning and instruction. 1994;4(4):295-312. doi:10.1016/0959-4752(94)90003-5

[31] Subramanian A, Price S, Kumbhar O, Sizikova E, Majaj NJ and Pelli DG, ‘Benchmarking the speed–accuracy tradeoff in object recognition by humans and neural networks’ (2025) 25(1) Journal of Vision (Charlottesville, Va) 4 <a href="https://doi.org/10.1167/jov.25.1.4">https://doi.org/10.1167/jov.25.1.4</a>

[32] Lewinski WJ, Hudson WB and Dysterheft JL, ‘Police Officer Reaction Time to Start and Stop Shooting: The Influence of Decision-Making and Pattern Recognition’ (2014) 14(2) Law Enforcement Executive Forum 10–13 <https://forcescience.docsend.com/view/3nqejqwrjvjvz9hf> accessed 10 November 2025

[33] Sandel WL, Martaindale MH and Blair JP, ‘A scientific examination of the 21-foot rule’ (2021) 22(3) Police Practice & Research 1314–1329 <https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2020.1772785>

[34] Esagoff, A.I., Heckenlaible, N.J., Bray, M.J.C., Pasuizaca, A., Bryant, B.R., Shan, G., Peters, M.E., Bernick, C.B., & Narapareddy, B.R. (2023). Sparring and the brain: The associations between sparring and regional brain volumes in professional mixed martial arts fighters. Sports Medicine (Auckland), 53(8), 1641–1649.

[35] Coswig, V.S., Ramos, S.P., & Del Vecchio, F.B. (2016). Time-motion and biological responses in simulated mixed martial arts sparring matches. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 30(8), 2156–2163. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001340

[36] Ambroży, T., Rydzik, Ł., Wąsacz, W., Małodobry, Z., Cynarski, W.J., Ambroży, D., & Kędra, A. (2023). Analysis of combat in sport Ju-Jitsu during the World Championships in fighting formula. Applied Sciences, 13(20), 11417. https://doi.org/10.3390/app132011417

[37] Larsson, M., Schepman, A., & Rodway, P. (2023). Why are most humans right-handed? The modified fighting hypothesis. Symmetry (Basel), 15(4), 940. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym15040940

[38] Taylor, S.E., Klein, L.C., Lewis, B.P., Gruenewald, T.L., Gurung, R.A. & Updegraff, J.A. (2000). Biobehavioral responses to stress in females. Psychological Review, 107(3), 411–429.

[39] Lane, A.M. (2025). CALM: Cultivating Awareness, Learning, and Mastery to Reduce Anger and Violence Through Combat Sports. Youth, 5(2), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5020045

[40] Kounalakis, S., Karagiannis, A. & Kostoulas, I. (2024). Balance training and shooting performance: The role of load and the unstable surface. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 9, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk9010017

[41] Mandache, R.A. & Grigoraș, C. (2022). Shooting training with light infantry weapons: An essential dimension of individual and collective training. International Conference KNOWLEDGE-BASED ORGANIZATION, 28(1). DOI: 10.2478/kbo-2022-0011.

[42] Johnston, A. (2024). Point of Impact Training Philosophy: Training for the Real World – The Science of Immersive Training Methodology. Warrant Officer Class Two (Retired), 7th Brigade Combat Behaviour Centre, Australian Army, Australia. Presented to Mrs Anne Goyne, Senior Psychologist, Defence Leadership and Ethics, Australian Defence College, Canberra ACT, Australia, 23 April.

[43] Rubio-López, A., García-Carmona, R., Zarandieta-Román, L., Rubio-Navas, A., González-Pinto, Á., & Cardinal-Fernández, P. (2024). Innovative approaches in pericardiocentesis training: A comparative study of 3D-printed mannequins and virtual reality simulations. medRxiv preprint. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.02.16.24302932

[44] Terrill, W., Zimmerman, L., & Somers, L. J. (2023). Applying video-based systematic social observation to police use of force encounters: An assessment of de-escalation and escalation within the context of proportionality and incrementalism. Justice Quarterly, 40(7), 1045–1076. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2023.2222819

[45] He, X., Jiang, D., Zhang, G., Ku, M., Soni, A., Siu, S., Chen, H., Chandra, A., Jiang, Z., Arulraj, A., Wang, K., Do, Q. D., Ni, Y., Lyu, B., Narsupalli, Y., Fan, R., Lyu, Z., Lin, B. Y., & Chen, W. (2024). VIDEOSCORE: Building automatic metrics to simulate fine-grained human feedback for video generation. In Y. Al-Onaizan, M. Bansal, & Y.-N. Chen (Eds.), Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (pp. 2105–2123). Association for Computational Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2024.emnlp-main.127

[46] Gutiérrez, Á., Blanco, P., Ruiz, V., Chatzigeorgiou, C., Oregui, X., Álvarez, M., Navarro, S., Feidakis, M., Azpiroz, I., Izquierdo, G., Larraga-García, B., Kasnesis, P., Olaizola, I. G., & Álvarez, F. (2023). Biosignals monitoring of first responders for cognitive load estimation in real-time operation. Applied Sciences, 13(13), 7368. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13137368