Since the early 1800’s, simulation – whether analogue or digital – has supported the cognitive development of personnel at all levels and enabled military forces to adapt in periods of rapid technological change. In two previous Cove articles (Reinvigorating Wargaming and DG TRADOC’s Professional Gaming List), I have explored the origins and definitions of wargaming; simulation is one of the many tools available to enable the conduct of wargaming.

Simulation – defined as the implementation of a model over time – provides a safe-to-fail, potentially adversarial environment where participants can experience the consequences of their decisions and actions. In training and education, mentor-led reflection can enhance cognitive performance through experiential learning. Alternatively, analysts can use the outcomes from simulation-based wargames to support force development and innovation.

Figure 1: Army’s Protected Mobility Tactical Trainer

The origins of wargaming in the Australian Army trace back to 1893 when General Sir John Monash, then a lieutenant, advocated for the use of wargames (manual simulations) as a professional development activity at the Naval and Military Club. In 1984 the Army War Game Centre (AWGC) was established and used manual (also known as analogue) computer assisted and automated (digital) wargames to support individual and collective training. Today, Army’s simulation capability resides in Land Simulation and Wargaming (LS&W) within the Directorate of Army Knowledge (DAK) (formerly the Army Knowledge Centre (AKC)).

This article will outline the benefits and limitations of simulation, describe the Army’s current virtual and constructive simulation capabilities, and outline how constructive simulation supported the recent Brigade Tactics Competition. In addition to promoting the use of simulation within Army, this article aims to highlight the benefits of the Brigade Tactics Competition and outline how individuals and units can prepare for this year’s event.

Simulation benefits and limitations

“All models are wrong, but some are useful; the practical question is how wrong do they have to be to not be useful.”

– George E. P. Box

Live, virtual and constructive simulations, or any combination of these three are an essential training tool for Army, but they cannot – nor should they – replace the requirement for field training exercises. While simulation enables our personnel to conduct training that might otherwise be unachievable, simulations are the implementation of a model, a representation of the real world, over time.

As noted by George Box in the quote above; all models are wrong, largely because they are a simplification of reality. After all, it is impossible to accurately replicate the real world. However, as noted in the quote, rather than just dismissing their utility, with an understanding of their limitations, models can still be employed to generate training benefits. This section will focus on the generalised benefits and limitations of virtual and constructive simulations.

Benefits. Virtual and constructive simulations provide the following benefits to Army:

Flexibility. Simulation platforms enable personnel to train on equipment and/or terrain they would not normally be able to access. It provides the opportunity to gain an understanding of future operating environments and alleviates the constraint of training area and equipment availability. Additionally, simulations can support a range of scenarios that present new challenges to training audiences, inform force development, and support the innovation of tactics, techniques, and procedures.

Repeatability. Unlike field training exercises, particularly those at or above Army Training Level (ATL) 5, virtual and constructive simulation activities can be easily reset – including to specific points of the activity. This allows commanders to confirm the achievement of learning objectives or address specific weaknesses demonstrated by the participants. Furthermore, once designed, a scenario can support multiple training audiences in successive days or over extended periods with minimal additional staff effort or resourcing. The use of simulation allows individuals and teams to learn or refresh basic lessons before commencing field training. This approach allows these limited training opportunities to focus on more advanced warfighting skills which may have also been ‘walked through’ in simulation.

Cost. Excluding the cost associated with establishing, operating, and maintaining a simulation capability; the cost of planning and executing a simulation-based training activity is significantly less than a comparable live training activity. The use of simulation reduces the consumption of resources such as fuel and other operating costs of vehicles and equipment. Conducting a distributed simulation, involving the connection of multiple sites into the single synthetic training environment, eliminates the requirement to concentrate personnel and equipment in one location for training. In the case of constructive simulations, it enables headquarters elements to exercise without the requirement to put soldiers and equipment in the field. Additionally, while some support staff are required to control the simulated units, the overall number of personnel required to support and participate in the training activity is significantly reduced.

Risk. Simulation allows personnel to undertake training on dangerous tasks without the associated risks; furthermore, it eliminates the environmental risks associated with field training exercises.

Figure 2: United States Naval War College using simulation in the inter-war years

Limitations. While simulation is an essential training tool for Army, its limitations may influence its inclusion in training activities. Some of these limitations are listed below:

Negative training. There is the potential that using virtual and constructive simulations will create negative training, particularly if there are limitations or errors associated with the models that affect the conduct of the training. Ensuring capabilities are accurately modelled within simulations requires on-going effort by the simulation staff and must be confirmed in scenario testing prior to execution. In individual training, the similarity of the platform interface with commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) computer games can distract the training audience. Furthermore, the lack of ‘fear factor’ and the absence of environmental factors such as heat or physical exertion can also influence the training audience’s perception of simulation-based training and can lead to over-confidence.

Integration with Mission Command Systems. Army’s current simulation capabilities do not have the ability to connect to our mission command information systems. As a result, the training audience is either using the simulation platform as part of the activity in lieu of their normal battle management system, or information from the simulation is being manually transferred into the battle management system. While the latter is preferable, it creates risks associated with human error and increases the number of exercise staff required to support activities, particularly at and above ATL 5. While this limitation will be addressed through the Land Simulation Core 2.0 (LS Core 2.0) project, it will remain a constraint in the short term.

Planning considerations. Unless re-using a pre-existing scenario, the planning considerations associated with simulation-based training are generally comparable with field training exercises. In addition to conducting the normally exercise planning process, the planners will need to maintain regular contact with the simulation planners in order to verify and validate the scenario throughout development. This ensures that all elements within the scenario are correct and that it will achieve the training objectives. Late notice changes to the scenario potentially introduce errors into the terrain, forces or scenario that may affect the execution of the training activity.

Army’s Virtual and Constructive Simulation Capability

LS&W is responsible to the DAK for the provision of simulation and wargaming support to Army. In this capacity they manage the Land Simulation Network (LSN) that provides a persistent network connection between the seven Battle Simulation Sites (BSS) to support local and distributed simulation-based education and training. In addition to these fixed facilities, a number of temporary LSN nodes were established in 2022 to provide simulation support at the Point of Need (PoN). Further expansion of the LSN is planned as part of the LS Core 2.0 project.

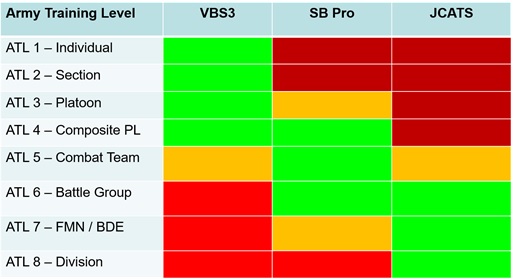

Army uses three software platforms to conduct virtual and constructive simulation-based training. These are Virtual Battle Space 3 (VBS3), Steel Beast Professional (SB PRO) and the Joint Conflict and Tactical Simulation (JCATS). These three programs, or a combination of programs, enables training up to and including ATL 7. The table below provides a basic overview of the level of training that each simulation is suited to support. Of note, there is overlap between the platforms and in these cases, the training objectives will influence which simulation software is used.

Figure 3: The employment of simulation platforms across the ATL.

The following provides a brief overview of each platform:

VBS3. Produced by Bohemia Interactive, VBS3 is COTS software that provides a virtual simulation capability to Army. VBS3 provides an environment where individuals and teams can conduct rehearsals; develop and refine their tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTP); and exercise decision-making up to ATL 4. The software allows training audiences to operate in a number of simulated roles, ranging from dismounted infantry through to the crew of an armoured vehicle. The models within the software replicate, albeit with some limitations, the experience the operator would have with the real-life system. When they look through a scope of their rifle, they see what they would see looking through the scope of an EF-88. It is relatively simple to learn how to operate with interface and controls similar to most computer/console games.

Figure 4: The Kapyong Battlefield in VBS3

In addition to enabling individual and collective training, VBS3 can be used to support the creation of training videos and other PME activities such as battlefield recreations. Last year, the Kapyong terrain was created within VBS3 to support PME activities for the 3rd Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment (3 RAR).

While highly suitable for individual training and collective training at lower ATLs, VBS3 is limited by the number of entities that can operate within in single simulation session. Despite this, it is often used to support ATL 6 or 7 activities where it is connected to a constructive simulation and provides a simulated sensor feed to the training audience. In this capacity, it not only replicates sensors normally available to the headquarters, but also provides a three-dimensional view of the battlespace created within the constructive simulation.

SB PRO. A COTS platform produced by eSim Games, SB PRO provides Army with a constructive simulation capability. While SB PRO can be used to support training at ATL 1 to 3, it is generally accepted that at this level VBS3 provides a better platform to conduct this training. As a constructive simulation, the software is able to control the reaction of entities within the simulation based on a series of behaviours selected by the user; this allows a single operator to control a platoon or even a combat team. In addition to supporting a two-dimensional representation of the battlefield – which is standard to constructive simulations – SB PRO is also capable of generating three-dimensional views of the battlespace. This enables the operator to see the battlefield from the point of view of any of their call signs. It allows training audiences to develop an improved understanding of terrain and its influence on land force capabilities and operations.

SB PRO has supported the All Corps Captain Course, the Combat Officer Advanced Course, Brigade Tactics Training, and the Brigade Tactics Competition. As a COTS product, SB PRO is relatively easy to learn with familiarisation training taking 2-3 hours. In addition, ADF personnel, through Army’s contract with eSim Games, are able to install a free copy of SB PRO Personal Edition (SB PRO PE) on their personal computers. This provides personnel with the opportunity to use the simulation software in their own time to conduct individual PME and helps to mitigate the perishable nature of simulation skills. Information on how to access the SB PRO PE home use licence and SB PRO training videos is available via Decisive Edge on ADELE (Course: Decisive Edge - Army Wargaming PME (adele.edu.au) (Defence personnel only).

JCATS. Developed in the United States of America by the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, JCATS – Army’s large-scale constructive simulation – can be used to support joint training, experimentation, analysis, planning, and mission rehearsal. It provides functionality across all Battlespace Operating Systems and enables the conduct of multi-sided exercises.

JCATS can support ATL 5 activities; however, it is normally used for ATL 6 and above. This is, in part, due to the increased complexity of the platform leading to longer scenario development timeframes and the requirement for four days of training for simulation interactors supporting exercises. In 2022, in addition to supporting Vital Prospect and Sea Horizon, JCATS enabled the conduct of a Command Post Exercise (CPX) as part of the Logistic Officer Basic Course. During this activity, the training audience was exposed to a wide variety of scenarios including resupply operations, casualty evacuations, vehicle recovery, transport and detention of Prisoners of War, reacting to Improvised Explosive Devices, and wild dogs attacking a ration store.

Creating a Safe-to-Fail Adversarial Environment for Decision-Making

Commander Forces Command Directive 01/22, Army Wargaming, sought to reinvigorate wargaming across Army through three lines of effort. In particular, it directed the establishment of a Brigade Tactics Competition as part of the Wargaming PME line of effort. The 2022 competition provided participants with the opportunity to explore the cognitive stress associated with peer-on-peer engagements against freethinking and adaptive opponents.

Conducted in a safe-to-fail environment, it enhanced tactical acumen of the participants through mentor-led reflection and individual learning. In designing the competition, LS&W sought to demonstrate and promote the use of Army’s simulation capability, enhance awareness of the SB PRO PE home use licence, and contribute to the end-state of the Army Wargaming Directive.

Figure 5: Red Forces surprise a Blue Force element in the 2022 Brigade Tactics Competition

LS&W conducted the competition in two phases over the period of July to November 2022. The first phase of the competition, using scenarios with a computer-controlled enemy, familiarised participants with the simulation platform and enabled units to select their team for the subsequent competition phase. The inter-Brigade competition involved teams engaging in real-time, force-on-force engagements in a cavalry or mechanised infantry scenario over the LSN from their home station location.

On arrival at the Battle Simulation Site, each team received the scenario and had an hour to conduct their appreciation, develop a plan, and deliver orders. At the conclusion of the engagement each team was debriefed by the central umpire and had the opportunity to conduct a detailed mentor-led After Action Review (AAR) using SB PRO.

Six units participated in the Brigade Tactics Competition and select participants were asked for their observations/recommendations on the activity:

As an OC what benefits have you seen from this competition?

‘Prior to a field activity I will look to employ simulation training with the Company’s Command teams to get a sense of where they are at prior to deploying. Ideally, this will be built over the weeks prior to a field exercise with the training oriented onto likely tasks the company will receive’.

‘The force-on-force nature of the activity tested the patrol commander’s skills in rapid enemy and terrain analysis, forcing them to consider how the enemy would manoeuvre to undermine the BLUFOR’s ability to achieve its mission. This provided an excellent opportunity for them to practice and refine their quick planning cycle, as well as demonstrate collaborative planning amongst the crew commanders. The value of testing their plans against a determined, intelligent and cunning enemy was immense and some key lessons I observed the Troop learn throughout the competition included:

- The ability to make an assessment of where they could safely trade security for speed.

- The importance of the principle of mutual support through “half guns/half visual” to achieve dispersal which greatly increased the Troop’s overall situational awareness and survivability.

- The critical necessity for accuracy in reporting, assessments and the art of providing valuable recommendations’.

Figure 6: A platoon commander learns a valuable lesson from reviewing the AAR footage from the Brigade Tactics Competition

As a participant, what key lessons did you learn from this experience and how were you able to incorporate these into successive iterations of the competition?

‘Patrols can and will act as independent entities. ROBC (Regimental Officers Basic Course) teaches you to split your patrols up but never send a single vehicle on a task. This competition taught me that when competing against a live, thinking, and well-drilled enemy, that the ‘battle run’ mindset will result in your destruction. You can afford to allow considerable separation between two vehicles as long as they maintain mutual support, but you must also be willing to take a risk and push that distance further to exploit opportunities. In a perfect world one cavalry patrol will fix, and the other will exploit an identified enemy, but circumstances will not always present this and opportunities may be missed if some risk isn’t taken’.

‘Accepting the risk of trading security for speed in order to win the initiative and dominate key and decisive terrain. This was particularly relevant in the first match; we reached the decisive terrain first which postured us to react to the red force advance. We not only secured the flanks (high ground) of the objective but adopted effective fighting positions which gave us a distinct advantage when contact was made. If we did not take the risk and advance at a rapid pace to our second report line (amber bounding), we would have had to contest the objective, and the scenario would have played out differently’.

As a participant, how has the experience of fighting against an adaptive, peer level opponent developed your tactical acumen?

‘This experience taught me that thinking that the enemy will not adopt and use Australian TTP’s and doctrine will result in my demise. I always knew this but this competition reinforced the idea. In particular, when I was flanked from a high-speed advance via a road that I considered ambush prone. I identified that avenue of approach but did not think the enemy would even consider using it as it was high risk and I was wrong. I learnt that to cover my flanks many tasks will become squadron efforts’.

‘As a commander, during my planning, I need to consider the enemy most dangerous course of action and my best response. I must assess whether I need to position my troop in close enough vicinity that we can rapidly get four guns on target or if use separation to deny a similar sized, near peer force the ability to flank me. In short, no longer will I always resort to patrols astride the objective or the road as that is easy to control, because that is too predictable for the enemy commander’.

As the competition progressed, the umpires noted improvement in the participant’s tactical acumen as the lessons learned from previous iterations were applied to subsequent scenarios. Reflecting on the conduct of the event, the umpires made the following observation:

The teams tended to rush to close combat and never really sought to gain situational awareness and subsequently then mass effects to gain the advantage.

In addition to the individual learning by the participants, this activity provides an opportunity for organisational learning – LS&W has retained all the AAR files generated throughout the Brigade Tactics Competition. Training Establishments can access these files to identify trends and training gaps; furthermore, units can use the AAR as part of unit PME activities. Finally, while the 2022 event has concluded, individuals and units are able to access the Brigade Tactics Competition scenarios to support professional development or unit training activities – contact your local BSS for more details.

Preparing for the 2023 Brigade Tactics Competition

LS&W has commenced planning for the 2023 Brigade Tactics Competition. Individuals and units interested in participating in this year’s event should commence their preparation now. Undertaking regular simulation-based training activities and in particular accessing SB PRO PE will ensure that personnel are familiar with the virtual and constructive simulation platforms. These training activities provide reps and sets in terrain analysis and decision-making which when coupled with mentor-led AAR and reflection enhances the tactical acumen of the participants and ensures they are cognitively prepared for the competition. In addition, regularly accessing the BSS ensures that personnel focus on fighting their opponent rather than trying to remember what keys to press as they undertake a peer-on-peer engagement in real-time.

Conclusion

In closing, I would like to take this opportunity to congratulate the winners of the 2022 Brigade Tactics Competition. 3 RAR won the Mechanised Infantry section of the competition and 1st Armoured Regiment won the Cavalry section of the competition. Of note, 3 RAR were unbeaten in their section of the competition. I would also like to recognise the School of Armour team who made both the Mechanised Infantry and Cavalry finals.

Figure 7: The winning team from 3 RAR

The investment and continued use of simulation provides Army with a readily accessible, low-cost training tool capable of preparing our people to operate in complex environments. Exploiting innovative approaches to simulation-based training, such as the conduct of a Brigade Tactics Competition, will contribute to the ability of our people to tackle a broader range of problems and enable our Army to be Future Ready.