Since WWI and the employment and deployment of physiotherapists in the military, the Army has acknowledged and sought to address the significant impact musculoskeletal injuries have on both capability and the health and well-being of members. While robust data is not at our fingertips (part of the problem), evidence suggests the rates of musculoskeletal injuries (MSKI) have remained relatively consistent over the decades.1-2

It is not that there haven’t been concerted efforts to address this burden. Examples of Army programs aimed at reducing injuries and improving capability with good scientific evidence include Rotary (now Aviation) Fit, the Defence Injury Prevention Program, the DSTG Human Performance Research network (HPRnet) suite of research projects, and policies such as the Physical Employment Standards. Many of these programs were successful while they were resourced and staffed, but most have not been enduring, and none are a complete solution to the Army’s MSKI problem.

This article argues that the Army and ADF have yet to implement a strategic and systematic approach to MKSI, but we are making progress. The Defence Injury Prevention Program from the early 2000s is probably the closest attempt so far; however, it did not have a truly whole-of-systems approach, nor was it sustained.

The ADF Health Strategy (DPN link) released in 2023, introduced a deliberate shift towards proactive health care with Force Optimisation being one of two key pillars. The Directorate of Force Health Protection (FHP) in JHC was established this year, with a focus on a more proactive approach to workforce health and readiness. While JHC are well placed to drive a systematic approach to reducing injury risk, the Army is the risk owner. Within the Army, both WHS and Army Health are key players – but neither can execute the solutions. Similar to the employment of joint fires, Force Optimisation should have centralised planning, with decentralised execution.

Integrated Systems Approach

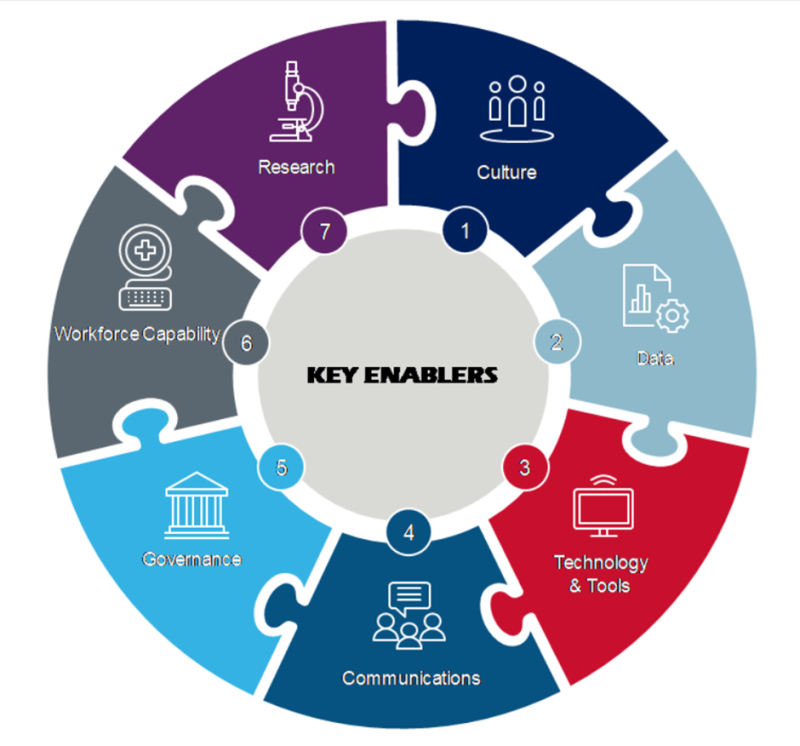

A Systems Approach to reducing injury risk, aka Force Optimisation, includes multiple enablers, depicted below.

ADF Health Strategy Key Enablers

There are plenty of existing initiatives across both the Army and the ADF that employ these enablers, to name a few:

- Reform Management to RCDVS Recommendation 64: This recommendation states that ADF is to establish an enterprise-wide program to monitor and prevent physical and psychological injury. The collection of data is the first step in an MSKI risk reduction approach, enabling improved analysis and reporting of injury burden.

- The Deputy Chief of Army Point of Need Care Pilot: Embedded physiotherapy officers at 1 Recruit Training Battalion and the School of Infantry are conducting primary and secondary prevention (including on-the-ground surveillance, training, education, and early intervention). This complements and bolsters the garrison physio departments, and enables improved communication direct to commanders, and addresses cultural barriers such as the stigma of being injured and just ‘soldiering on’.

- Workforce growth: Ukraine is a prime example of how disease and non-battle injuries can degrade capability.3 Army has recently acknowledged the uniformed physiotherapy trade has long been underrepresented compared to other health trades and realised the force multiplication value in having physios forward in the fight. The proposed growth to the physio trade over the next few years will see the uniformed physios push into training establishments, units, and headquarters to provide effects at tactical, operational, and strategic levels and have improved capacity to support LSCO when required.

- JHC Force Health Protection (FHP) Directorate: As of January this year, proactive healthcare from a population level now includes an Occupational Health and MSKI team, represented at a strategic level for the first time. While 2025 efforts have focused on recruitment and surveillance, FHP also supported the Combined Joint Theatre Medical Component during Exercise Talisman Sabre 2025. As the team progresses toward final operating capability, business-as-usual operations will enable the single services to design and implement programs and training continuums, as well as enhance MSKI surveillance and analysis.

- Army’s Strategic Partnerships: Both the Australian Institute of Sport (AIS) and BHP have force optimisation needs, albeit through a different lens to Army. BHP have had significant success with occupational health and ergonomic programs, which have reduced injury rates among their employees and achieved impressive cultural shifts around gender equity. The AIS facilities and subject matter experts in physiology, nutrition, and recovery offer a wealth of knowledge that directly translates to a military population. The opportunities to learn and share from both these partnerships can elevate how the Army tackles the MSKI problem.

Barriers to progress

A significant barrier to effecting meaningful change in the injury arena has been a lack of valuable data to define the root causes of the injury burden. While existing data from the health system is less than optimal, a JHC priority is an ADF health surveillance system that will provide meaningful (i.e., actionable) insights to inform and support targeted prevention strategies and programs. For example, surveillance data may inform the design of the training continuum and task exposure risk profiles. The WHS Sentinel data is helpful in highlighting acute injuries that have clear ergonomic or environmental contributing factors. But for the majority of physical injuries, the contributing factors and underlying causes are multi-factorial, so putting a simple control in place will be ineffective.

Another barrier is striking the right balance between resisting change and rushing to failure. I have witnessed both ends of that spectrum, with uniformed physios not being supported to conduct primary prevention and education, as it breaks the mould of what a physio ‘should’ be doing. I’ve also seen regulations and governance circumvented (usually through ignorance, not malice) to get results, but at the expense of following evidence and best practice.

Way Forward

The Army needs an integrated, strategic approach to reducing injury risk that enables actionable change at the unit level. Policy must align with the latest evidence, that is a given, but improving the communication and implementation of these changes is how the Army will reduce the risk of injuries. While the Force Health Protection team in JHC will provide a centralised coordination function, the execution must be embedded in Army. Noting that command is accountable for the MSKI burden already; embedding physiotherapy officers within units and bringing together safety, health and command will enable commanders to make data-informed decisions on how to manage and reduce injury risk from training establishments to the battlefield.

The caveat is that this requires the Army and the ADF to adopt organisational change – and have it endure the posting cycle. To achieve lasting change, we need to challenge the status quo while adhering to regulations respectfully. The term ‘integrated’ is used so frequently, yet across ADF siloes, it still remains. Commanders, civilian health staff, uniformed health members, WH&S reps, recruits, and soldiers all need to be involved. We are on our way to this systematic approach to have a fighting fit force, as long as we all work together.