‘They came on in the same old way, and we sent them back in the same old way.’

– Wellington

A criticism sometimes levelled at the Military Appreciation Process (MAP), both its Army and Joint variants, is that its mechanistic focus on process can stifle creativity. This criticism is not without merit, especially when the MAP is applied to address unconventional or wicked problems. This article does not propose any ‘silver-bullet’ solutions to silence this criticism; however, it does address it by proposing some easy ways to inject an enhanced level of creativity and innovation into the process. What follows are three simple ways to enhance creativity within the MAP, which the author has successfully implemented during multiple planning groups, and that can be implemented without adding to the time, number of steps, or volume of outputs required.

1. Use metaphor building as an alternative situation framing method

This method fits within the Joint Military Appreciation Process (JMAP), though it can also be conducted at the outset of the Army’s Staff MAP (SMAP) or Individual MAP (IMAP) if desired. To quote the doctrine, sub-step two of JMAP step one, ‘Framing’: ‘enables the commander and staff to develop an enhanced situational understanding. Framing is used to deconstruct complexity and to ensure that the correct problem or series of problems are fully explored to help inform more detailed planning’.

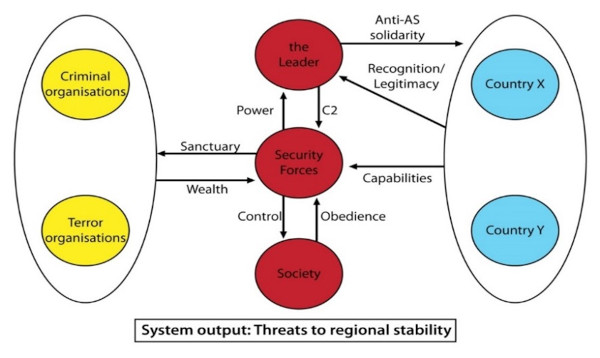

Although there are several possible methods to achieve this, only one is featured in the doctrine: systems mapping. In this method, planners (or a planning group) represent actors within the operational environment as ‘nodes’ and their relationships as ‘links’, which may be seeking to either positively or negatively influence other actors within the system. Two systems maps are produced: the observed system (what the operational environment looks like now) and the desired system (what we want it to look like). The doctrine’s example of these systems maps is shown below, with the observed system at top and the desired system at bottom. Once the maps are drawn, planners compare them and identify differences. These are noted, to be revisited later in the process when courses of action are checked to confirm that they have been designed to change the system from that observed to that desired.

In practice, this method is a quasi-scientific parody of complex systems mapping, without the detailed data that underlies the mathematical models produced by complexity scientists. Without supporting data, the ‘observed system’ diagram in particular risks being a misrepresentation based the planning team’s unconfirmed ‘best guess’ about the nature of the operating environment and the relationships between the actors therein.

Another problem with this method is one of implementation: planning groups often get bogged down in minutiae. Discussions about which actors are important enough to be included in the map and in which ways are they linked can take hours. Often the diagrams end up including so many nodes and links that they become unwieldy and ‘the forest is lost for the trees’. Further, an early focus on every minor detail takes time and often leads to hurried completion of half-finished products to meet the planning timeline, resulting in a final product that is half overly-analysed and half under-analysed.

An alternative method that can be used to achieve this step’s intent – that being, in the doctrine’s words, ‘to deconstruct complexity and to ensure that the correct problem or series of problems are fully explored’ – is creative metaphor building. In this context, a metaphor is a single, holistic, and imaginative output that needs to encompass all of the parts of the system under observation. Instead of systems mapping, planners working in small groups (three or four is optimal) spend 10-15 minutes drawing a picture that constitutes a metaphor explaining the observed operational environment.

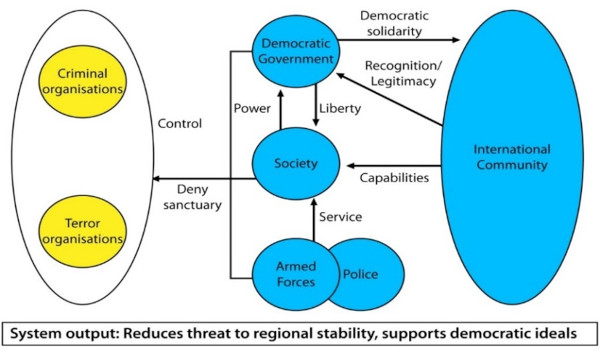

After a 15-minute break – which is important as it clears the mind – another drawing is completed showing a metaphor representing the desired system. Two examples of desired systems metaphors are shown in the image below. Importantly, for this method to work the desired system metaphor must represent the entire operational environment and all of its parts, without breaking this down into an analysis of individual actors or their specific relationships. The metaphor needs to concentrate on answering the question ‘what do we want the entire operational environment to look like?’

The quality of the drawings does not matter; the metaphors themselves and what they say about the nature of the observed and desired systems is what matters. Planners do not need to be artists, but they do need to be willing to ‘have a go’ at drawing, even if this is out of their comfort zone.

Once the drawings are complete, each group of planners explains their metaphors to the other groups, first describing what they have drawn and why they think their drawings represent the observed and desired systems. Discussion must focus especially on the components of the desired system. According to each metaphorical drawing, who might be the most important actors and why, and what are their behaviours? How might our own actions shape these actors to behave this way? The answers to this last question are the most important outcome from this method as they will indicate what problem(s) the plan must address and some implied requirements for solving them. These answers need to be captured for use in subsequent planning steps as they link this method to the rest of the JMAP in the same way as the doctrinal systems mapping outputs.

This approach has a significant creativity advantage over the doctrinal method. While systems maps are designed to be grounded in reality, metaphors are designed to represent reality in a radically different way. They are therefore much more likely to result in creative or innovative ideas about what the desired system or operational environment may look like. This is further enhanced by focusing metaphor building on the whole system first and only later looking at its parts.

An addition to this method, which is more difficult and takes longer but produces more creative results, is to redraw each metaphor without using any of the symbols used in the original metaphor. An explanation of how to do this, which uses an analysis of the movie Jaws as an example, can be found here. This addition only works if the first metaphorical drawings are made without planners holding any ideas ‘in reserve’ to use in the second metaphor. The planning team’s discussion of their completed drawings should examine their second metaphors, identify any new insights they give that are different to the first metaphors, and the significance of the difference.

2. Do not identify limitations until the end of Course of Action Development

In both the JMAP and Army’s MAP, limitations are determined near to the beginning of the process as a sub-step of the Mission Analysis step. Limitations are broken down into constraints (actions imposed by a superior commander that must be done) or restrictions (prohibitions on activities, which are imposed by a superior commander). Both constraints and restrictions are listed, to be referred to later when determining courses of action. The intent of this sub-step is to ensure that all courses of action remain within the boundaries imposed by the constraints and restrictions. A by-product of the early placement of this sub-step is that it curtails creativity by prompting planners to focus on what cannot be done instead of what might be done.

To enhance creativity, the MAP sub-step that determines limitations should be moved to later in the process. Specifically, it should be the second-to-last sub-step of the Course of Action Development step, occurring immediately before each course of action is tested against the FASSD criteria that confirms they are feasible, acceptable, suitable, sustainable, and distinguishable. At this point in the MAP, several possible courses of action (doctrinally, at last three) have been developed. Once constraints and restrictions are identified, planners should determine the minimum adjustments required to each course of action to ensure that it has accounted for them.

Although a simple change, moving this sub-step to later in the process removes planners’ tendency to stifle their own creative ideas due to concerns that those ideas may not conform to the limitations identified.

3. Establish a ‘good ideas fairy visit’ list

It is common for planners to want to jump straight into course of action development even though this does not doctrinally occur until after Scoping and Framing (for JMAP) and after Mission Analysis (for both JMAP and the Army MAP). Often, planners who have ideas about possible courses of action are reminded by their peers that ‘we are not up to that step yet’, at which time they stop explaining the idea and re-focus on the step they are supposed to be completing.

The reason for this ordering is that it ensures planners understand the operational environment and what their superior commander needs them to do before they start developing solutions that may not be fit for purpose. Yet, this curtailing of discussion of ideas relating to course of action development can come at the cost of creativity. Good ideas, deferred until later, may be lost if not recorded. This is where the sarcastically-named ‘good ideas fairy visit’ list can assist.

At the outset of the MAP dedicate a whiteboard, pad of butcher’s paper, or similar – located in a prominent and easily accessible spot within the planning area – as the ‘good ideas fairy visit’ list. Throughout the entire planning process if someone has an idea about a possible course of action or activity that may be part of one, it should immediately be written on the list.

This is a good way to capture ideas that may otherwise be lost, but it does not enhance creativity alone. To achieve this, another aspect must be added to the activity: planners need to be encouraged to record ideas that they specifically think are not feasible, or that the commander would never approve, or that sound outright ridiculous. If a planner feels the need to self-censor before mentioning an idea to the planning group, this is precisely the kind of idea that needs to be recorded.

What is the most ridiculous sounding course of action you can think of? For example, what about inserting a company by paddle board, or disguising an armoured force from aerial reconnaissance by putting an equal number of taped-together ration boxes over each vehicle? These ideas sound silly, and that is precisely why they should be recorded. While not necessarily feasible in their initial form, they are often the most creative ideas that emerge during the entire planning process. For this method to work, planners need to be unafraid of being ridiculed. This means that everyone must be encouraged in advance to express ridiculous-sounding ideas. The lead planner needs to ensure that that planning area is a safe and rewarding space in which this can occur.

The final part of this method is that the ‘good ideas fairy visit’ list is reviewed early in the Course of Action-Development step. This achieves two things. First, the list will serve as a collective memory-prompter, ensuring earlier ideas are not lost and that they can be explored now that the planning team has reached an appropriate step in the process. Second, the crazy-sounding ideas should be further developed. What might it take to make them feasible? While their original form may not work, a variation might actually be the innovative solution the planning team is seeking.

Every idea on the ‘good ideas fairy’ list should therefore be seriously evaluated before a determination is made to discard it, modify it, or include it as-is within one or more courses of action. If done right, the outcome of this review will be the enhancement of creativity within course of action development.