Note: The thoughts expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and not formal advice on behalf of the Australian Army.

Bottom Line Up Front:

- Army builds strong soldier identity – but often at the expense of the civilian self.

- This imbalance reduces identity resources, increasing risk to wellbeing during service and at transition.

- Social Identity Theory and mapping provide a way forward, allowing Army to expand identity resources by developing both soldier and civilian identities together.

Background

Last year, Chief of Army LTGEN Simon Stuart challenged Army to inspire young Australians to serve by telling the story of the intangibles – purpose, identity, belonging, mateship. He said service can make people “more capable, more confident, more resilient” and at the same time “better citizens, closer connected to community and to nation.”[1] Army has always delivered on the first promise. Our systems, training, lifestyle, and culture reliably produce capable, confident, resilient soldiers and cohesive teams. However, Army falls short on the second promise: building up soldiers as citizens with closer connections to community outside the ADF. Put simply, Army is strong at shaping and supporting its people as soldiers, but poor at helping them stay connected as civilians.

The result is uneven growth between soldier and civilian selves. Like watering just one side of a garden, one half flourishes while the other fades. Throughout service, a soldier’s identity and support networks sink deep roots into Army life. To them, the garden feels green, thriving and healthy. It’s often others – like family, psychologists, or old friends – who notice how the civilian self is fading. It is typically at or after transition that the soldier peers beyond the green side of the garden. What comes into view is the withered half – and with it, regret for having left the civilian self-untended.[2]

Extensive research on the military-to-civilian transition (MCT) shows how soldiers’ mental health is impacted when leaving service[3]. Rates of psychological disorder and suicidality are higher in veterans compared with the average, especially in the first few years post-service[4]. There is no single root cause for these impacts. However, two identity processes are shown to influence mental health outcomes during MCT: difficulties with identity loss, as the dominant ‘soldier self’ and military ties fall away; and difficulties with identity gain, as civilian identity and connections are rebuilt[5]. Responding to these risks, Army concentrates its efforts on transition programs[6]. This is effective; however, it comes too late in service.

If Army seeks to decrease risk at transition, increase wellbeing in service and realise the Chief of Army’s ambition for service to develop better citizens with closer connections to community, it must rethink its approach to identity. We must ask questions such as:

- What is it about Army’s approach to identity that fosters uneven growth between soldier and civilian selves?

- What are the risks of an overdeveloped soldier identity?

- How and why does civilian identity tend to fade across years of service?

- What are the benefits to Army when soldiers maintain strong civilian identity and connections?

To begin answering these questions, we need to look closely at how Army currently shapes identity from the moment of enlistment.

Current State

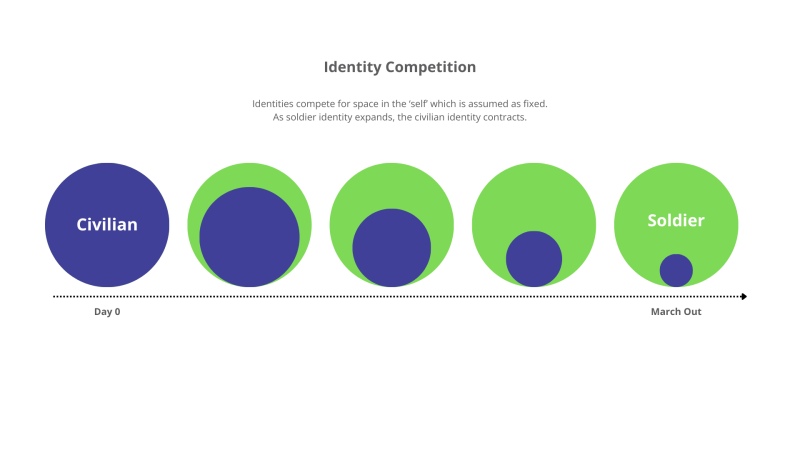

Becoming a soldier changes identity. Identity includes the personal – how we see ourselves – and the social – the groups we feel connected to. Army’s identity process begins intensively at Kapooka. Within hours of arrival, heads are shaved, comforts removed, uniforms issued, and first names gone. Like infants, recruits are taught to walk and talk again as soldiers. Army’s message is clear: forget who you were; you’re a soldier now. Powerful rites of passage like Kapooka create an environment of depersonalisation. These environments are ideal for imprinting new identities as they work to minimise individuality and maximise group cohesion[7]. However, such an environment also creates identity competition where the civilian self must shrink to allow the soldier self to expand. While this may be useful during basic training, it sets up a culture where civilian identity and connections are not relevant to service. Identity becomes a zero-sum game where the ‘soldier self’ dominates at the expense of the civilian self.

Figure 1: The Zero-Sum Approach to Identity. Soldier and Civilian selves compete. Increase in soldier identity is linked with decrease in civilian identity.

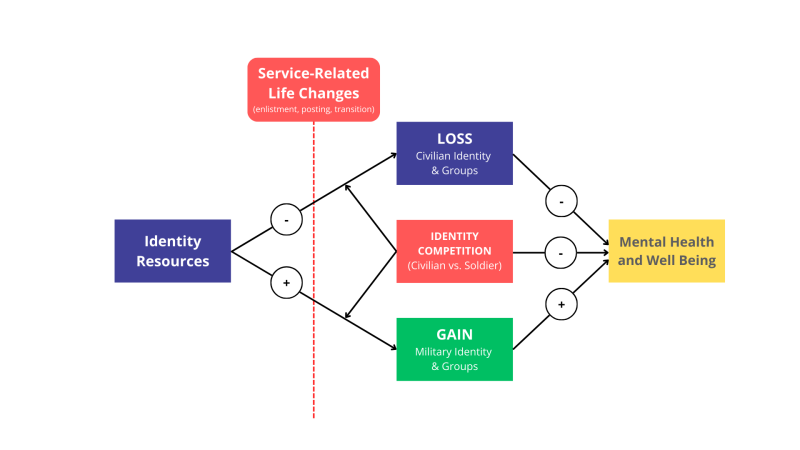

After basic training, service-related life changes such as postings, exercises, and deployments reinforce identity competition at the social level. Service demands disrupt civilian social connections to family, friends, and community[8]. Further, social connections tend to rewire within Army, through live-in accommodation or DHA patches, ADF Sport, on-base gyms, and frequent socialising with other soldiers. These individual and social shifts accumulate, reshaping the balance of social connection and identity across service.

Army may not intend to set up identity competition or deliberately design structures that centralise social connection within Army, yet the struggles that surface during transition strongly suggest that its approach has negatively impacted civilian identity and social connections during service. The negative impacts are hidden during service because Army compensates for identity loss by becoming the central source of connection and identity. However, the stability of identity resources depends on holding multiple memberships across different self-categories – as soldiers, as civilians, as Australians, and beyond. Multiple group memberships strengthen identity resources, which in turn support mental health[9]. Under the current ‘zero-sum’ approach, Army risks reducing these resources across the service life cycle. Adapting an empirical framework from the Social Identity Model of Change[10], we can see how losses and gains over time are likely to erode identity resources overall.

Figure 2: Social Identity Model of Change adapted to reflect service-related life changes, identity loss, and identity competition. Negative impacts on mental health indicated by (-), positive impacts indicated by (+).

Future State

Army does not know enough about how identity develops across the service life cycle. Lack of knowledge about identity creates risk to our people. With neither a unifying theory nor a baseline measure of social connectedness at enlistment, and no clear way to track changes over time, Army is stuck trying to fix identity at the point of transition. To be proactive, Army needs both a framework and tools to approach identity. Social Identity Theory provides the framework, and social identity mapping provides the first tool.

1: Adopt Social Identity Theory

Social Identity Theory explains how belonging to groups shapes who we are, influencing resilience, behaviour, and wellbeing. It is especially useful for Army because it highlights both the benefits and the risks of its approach to identity. The theory can explain how a strong soldier identity fosters cohesion, resilience, and motivation, while also accounting for the impacts that follow when civilian identities fade. Crucially, it gives Army empirical leverage to understand the mechanics and dynamics of identity, how they influence health and wellbeing, and how they change across the service life cycle. It also provides a testable framework for designing strategies aimed at increasing identity resources and making soldier and civilian selves compatible rather than setting them in competition.

2: Map and Measure Social Connectedness

Social Identity Mapping[11] offers Army a practical first step in putting this framework into practice. By mapping recruits’ group memberships at enlistment, Army can establish a baseline measure of civilian identity and begin to track how the soldier identity develops alongside it. Mapping can then be repeated at key points of change such as posting, deployment, or transition to track shifts in identity resources. Beyond measurement, it also serves as a psycho-education tool, helping soldiers reflect on their connections and understand the protective role of maintaining both civilian and soldier identities. In this way, it functions both as a health metric and as a means of strengthening resilience.

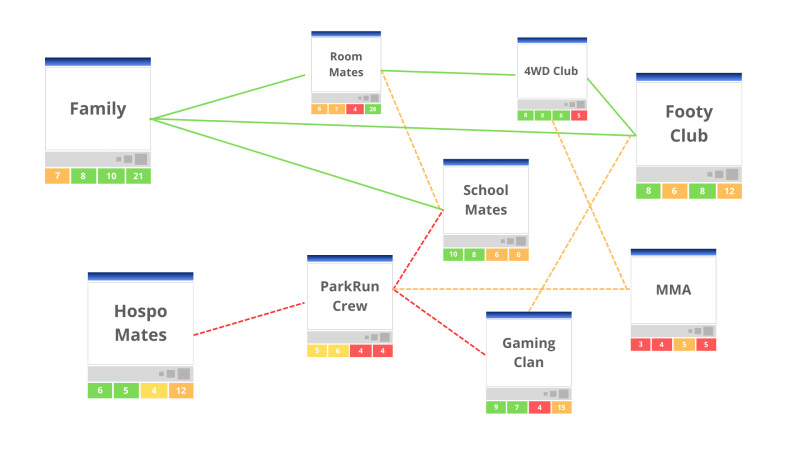

To see the potential of social identity mapping, imagine charting the social connections of an average candidate at a very early stage of training or on enlistment. They are likely aged 17–25[12], experimenting with identity and moving between several social groups. At this point we could visualise and measure what groups they belong to, how connected they feel, how much time they spend with each, and whether those groups are compatible with one another. The map might look like this:

Figure 3: Pre-Enlistment Social Identity Map. Size indicates importance. Lines connecting groups indicate compatibility. Numbers represent feelings of connection, similarity, support, and contact days per month.

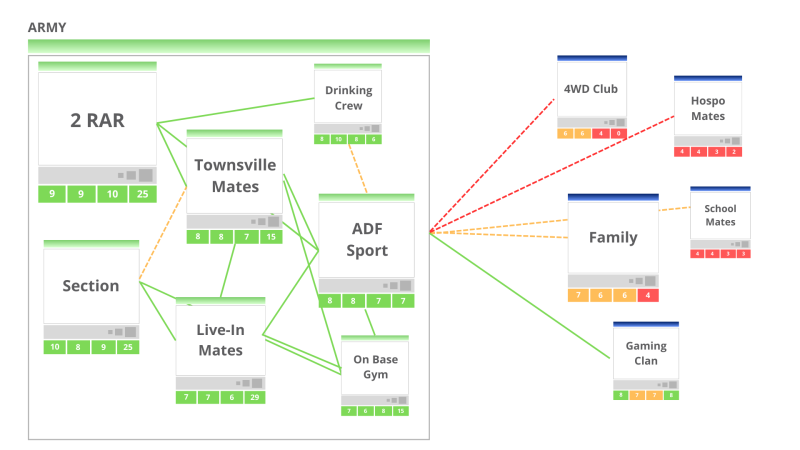

In the initial years of service, following training and the first posting, measuring connectedness again would likely show drastic changes. Army becomes the primary source of social connection, with significant loss to civilian group membership. As a result, overall identity resources decline. Fewer identity resources mean less protection for mental health, less flexibility when challenges arise, and fewer buffers outside Army life. The soldier may feel highly supported within the military, but increasingly isolated from civilian networks. Over time, this imbalance not only heightens vulnerability at transition but also strains families, weakens ties to family and community, and diminishes the broader benefits of service that Army aspires to deliver.

Figure 4: The social ‘centre of gravity’ is now Army, with some civilian groups lost and others weakened. Civilian social connections are increasingly perceived as incompatible with Army.

Conclusions

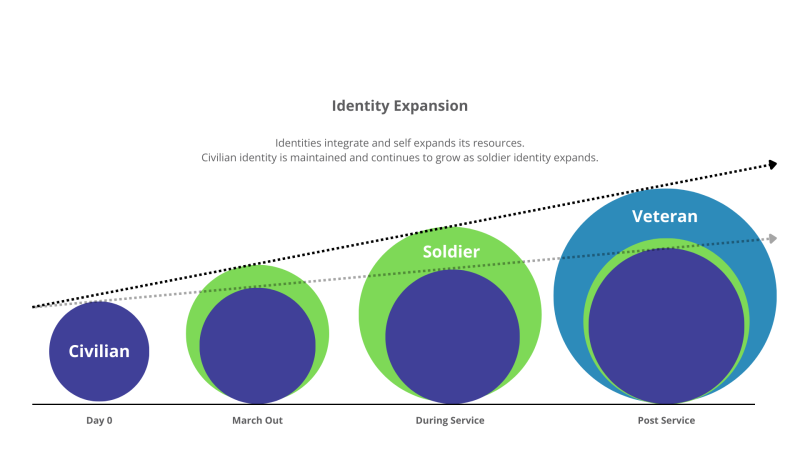

Army already excels at building soldiers. The next step is to expand its identity-building capability to deliberately develop and maintain civilian identity throughout service, completing the ambition laid out by the Chief of Army for confident, capable, resilient soldiers who are also citizens closely connected to their communities. This would allow Army to move from an identity competition model to an identity expansion model, where service benefits from a strong soldier identity without incurring the cost of losing the civilian self.

Figure 5: Soldier identity expands around the civilian self, which continues to develop. After service, the soldier identity recedes while a veteran identity grows in its place.

The expected implications are significant: fewer difficulties at transition, a protective effect for mental health during service, and the possibility of longer retention as tension between soldier and civilian selves is reduced. The central questions – how Army’s approach fosters uneven growth, what risks come from an overdeveloped soldier identity, and what benefits follow when civilian connections are maintained – now become directions for research and reform. Systematically answering these questions allows Army to use identity as a force multiplier, where stronger, integrated selves are empowered to provide stronger service.

End Notes

[2] “The Military Mode | APS.”

[3] Flack and Kite, “Transition from Military to Civilian”; Thompson, Veterans’ Identities and Well-Being in Transition to Civilian Life - a Resource for Policy Analysts, Program Designers, Service Providers and Researchers; Wakefield et al., “Brothers and Sisters in Arms.”

[4] Royal Commission into Defence and Veteran Suicide, vol. 1.

[5] Pedlar et al., “Military-to-Civilian Transition Theories and Frameworks.”

[6] Joint Transitions Authority, Transition | ADF Members & Families | Defence

[7] Haslam, Psychology in Organizations.

[8] Hughes, Australian Military and Veteran Families Study.

[9] Charles et al., “Diversity of Group Memberships Predicts Well-Being.”

[10] Haslam et al., “Life Change, Social Identity, and Health.”

[11] Bentley et al., “Social Identity Mapping Online.”

[12] “A Deep Dive Into Our Tiny Recruitment Pool | Future Forge.”

This idea resonates with me. We recruit people because they are suitable, so why do we need to 'break them down' or remove their current identities? Your article shows clearly that the individual and the Army is much better served by building on those already established foundation identities.

Some critics will offer alternatives like 'but that's how we've always done it'. While that is correct, it also means that we will always get the same results. Sometimes that is good enough, but like you I think we can always look to do better.

Great article, thanks for sharing your thoughts!