As a RAE Troop Commander in the Army Reserve and digital native, I get to see how quickly battlespaces are evolving. As many of us have seen, drones are changing the character of war before our very eyes. The seemingly endless hours of first-person view footage are stark. These aren’t just little toy gadgets that make a buzzing noise; they are being employed in offensive, defensive, and HADR operations around the world. The proliferation of drones across the modern battlespace is not just a technological shift; it’s a tactical and cultural one. From Ukraine to the Indo-Pacific, drones are reshaping how reconnaissance, targeting, and navigation are conducted and so much more.

Yet within our own Army, despite having sovereign drone assets (Reference: DEFGRAM 398 Army Provisioning of Sovereign Very-Small Uncrewed Aircraft Systems (vsUAS)) and a Defence Remote Pilot Licence (DRePL) course, we remain slow to integrate these tools into day-to-day operations.

The problem isn’t capability, its clarity.

Confusion around policy, coupled with risk-averse command environments, is stifling innovation and delaying progress. If we are serious about preparing for future warfighting, we must empower our soldiers to use the tools already at our fingertips.

For brevity, when I refer to drones, I refer to vsUAS (very small Uncrewed Aerial Systems) such as the sovereign manufactured drones that have recently entered service (Grabba Technologies’ Mozzie, Boresight’s BS-350 and AMSL’s ASTIIA) and are dismount-portable.

Drones Aren’t New, But We’re Still Catching Up

Drones are not a new capability. The Australian Defence Force has been trying to rapidly acquire and integrate them for years, recognising their value in modern conflict. Despite this need, progress at the unit level remains slow.

We are time-poor, constantly preparing for the next exercise, deployment, or readiness cycle. Adding another training burden feels overwhelming. But this isn’t just another capability; it’s one that can keep us alive. The initial effort to stand up a drone program is small compared to the tactical advantage it provides. With clear policy, CO support, and a short training course, we can get drones in the air quickly. It’s worth the effort.

The Opportunity: Drones as a Tactical Force Multiplier

I think sappers are some of the cleverest soldiers in the Australian Army; I know I am biased, but some of the things that they can do is nothing short of incredible. Often operating on ‘the smell of an oily rag’, they get the job done. Drones offer my sappers a tactical way to enhance their core tasks safely and effectively. Reconnaissance is a prime example.

Traditionally, this involves exposing those soldiers to a degree of risk – moving through contested terrain, often under time pressure, to gather information. A drone can do this faster, safer, and with greater persistence (acknowledging the logistics support required for people and assets). A drone can scan terrain, identify obstacles, and even assist in route planning. For targeting and ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance), drones provide real-time data that can be fed directly into decision-making cycles. Drones also support navigation, allowing troops to orient themselves in complex environments without relying solely on maps or line-of-sight.

These aren’t hypothetical capabilities. We already have sovereign-made drone platforms and a Defence-endorsed training pathway in the DRePL. The technology exists. The training exists. The assets exist. What’s missing is the operational integration and the confidence to use them.

For example, a vsUAS (very Small Uncrewed Aerial System) can be flown with unit CO support and a soldier completing a less-than-a-week training course, and straightforward governance oversight. While there are some reasonable constraints (height, speed, location and more), it is possible to get these assets in the air quickly.

The Problem: Policy Paralysis and Cultural Constraints

Despite the clear utility of vsUAS, there are persistent barriers to their use. My sappers are crying out to use these tools but instead of innovating, are being told to ‘just do their job’. The most frustrating is the lack of clarity around what we are ‘allowed’ to do. Policy documents are vague, impractical, often interconnecting, and rarely accessible to junior leaders. When I’ve tried to initiate drone training or include drones in exercises, I’ve encountered delays, hesitation, and resistance – not because the idea lacked merit, but because it was perceived as risky.

What if something goes wrong? What if it breaches policy? What if it sets a poor precedent? Doesn’t this distract from our core business? What about the training burden? Do we want to be distracted with this while we’re generating readiness for the next exercise?

This culture of risk-aversion creates a chilling effect. Soldiers are eager to learn and innovate, but they’re constrained by layers of bureaucracy. Even simple initiatives, such as familiarisation sessions or trial flights, can be delayed for weeks due to approval processes. In a time-poor Reserve environment, these delays are costly. They erode momentum, discourage initiative, and ultimately leave us less prepared.

What’s most concerning is that this issue isn’t being addressed. While Army talks about innovation and future warfighting, the practical barriers to integrating emerging technologies at the unit level are often ignored. We need senior leaders to bridge the gap between strategic ambition and tactical reality rather than being paralysed through analysis before the next promotion cycle.

I think vsUAS should be tactically integrated with every corps; the ability to ‘see around the bend in the road’ can save lives, enable us to project forces further, and give us decision making superiority in a contested environment. Greater uptake in innovation can yield significant capability benefits. It allows us to continue to be brilliant at the basics, and better for the future.

The Way Forward: Empowerment through Clarity and Culture

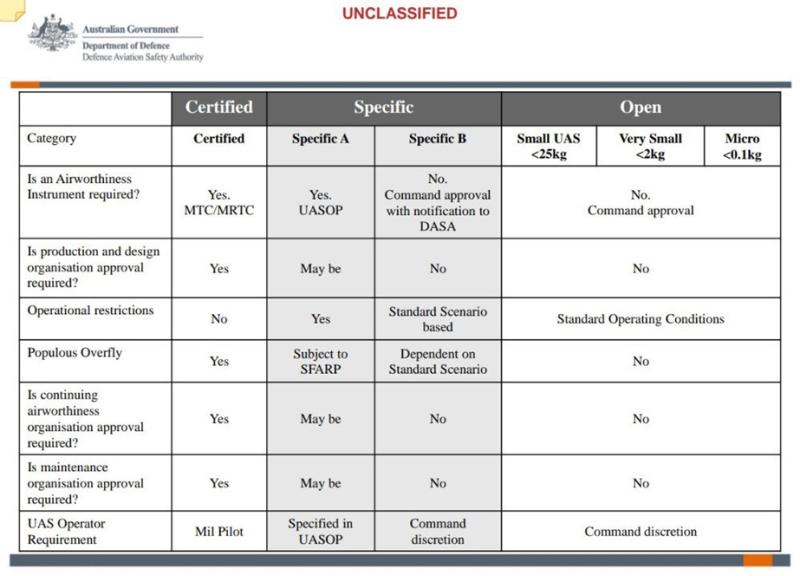

All Army units are already covered by an ATOUAS for vsUAS operations. To begin flying, units simply need CO approval, to maintain flight logs, asset and pilot registers (for example, DRePL holders), and a record of any incidents. These records must be auditable by HQAVNCOMD. Under current Defence Aviation Safety Regulations (DASR), vsUAS sovereign drones under 2kg fall into the “open category”. The operating requirements are straightforward:

- Operate below 120m AGL (Above Ground Level). For reference, the Hilton Surfers Residences Boulevard Tower in Surfers Paradise is 120m tall and is 34 storeys tall, so there is plenty of space to operate!

- Maintain Visual Line of Sight (VLOS)

- Stay >3nm from controlled aerodromes

- Remain >30m from the general public, and not over populous areas

- Use qualified pilots (DRePL or equivalent)

- Limit to one drone per two operators

These conditions are not restrictive, rather they’re enabling. They allow units to operate drones safely with minimal overhead. At the tactical level, these are appropriate and reasonable ‘rules of the road’.

Excerpt from the Defence Aviation Safety Authority Self-Paced Awareness Module: UAS Regulation (Unclassified)

Every unit with a reconnaissance role should integrate drone training and be developing their own SOPs. This doesn’t require new policy, just a directive encouraging use of existing assets. Training and governance establishment can be established before the assets arrive. The DRePL is already being exported from the School of Artillery and work is already underway to bring these new assets to every unit.

Units need space to experiment. Mistakes should be treated as learning opportunities, not liabilities. Utilisation of the new vsUAS is low-cost, high-impact, and entirely achievable within current structures. More importantly, it aligns with Army’s broader goals of adaptability, innovation, and future readiness.

Not just Sappers: Line of Sight Signals Planning

As a commander, if you haven’t thought about how drones will impact the way you operate, you’re already late.

Imagine a signals detachment is tasked with establishing a secure communications relay across undulating terrain. Before deploying antennas, the detachment commander launches a vsUAS to assess line-of-sight between key nodes. Flying below 120m and within visual line of sight, the drone identifies a ridge obstructing the planned signal path. The team adjusts antenna placement, saving time and avoiding ineffective setup. The drone also confirms safe access routes for cable runs. This simple, compliant use of vsUAS enhances planning, reduces setup time, and improves operational effectiveness; demonstrating its value in supporting tactical communications tasks.

Getting Off the Ground: A Call to Action

On a practical note, HQAVNCOMD has done excellent work establishing the Authority to Operate (ATOUAS) and publishing the UAS Commencement of Flying Guide, which includes a template minute for unit COs to authorise vsUAS use. The School of Artillery has also developed a robust DRePL course, ideally suited for very small UAS. These resources are a great starting point for any unit looking to establish drone capability.

The changing character of war demands that we adapt, not just in our equipment, but in our mindset. Drones are key enablers of a smarter, safer, and more agile Army. For soldiers, they offer a chance to enhance effectiveness, reduce risk, and better support the broader force. This concept is not unique to RAE only; I know that drones are already being employed by our friends in infantry, cavalry, and artillery. It doesn’t take much to think how they could be employed to support signals, transport, ordnance, and more.

But to realise this potential, we must cut through the fog of policy and empower our people. The assets exist. The training exists. The policy exists. It’s time to stop waiting and start flying. Let’s get to work.

References:

- HQ AVNCOMD. (2025). UAS Commencement of Flying Guide – Version 2. Australian Army Aviation Command.

- Department of Defence. (2024). DEFGRAM 398 – Army Provisioning of Sovereign Very-Small Uncrewed Aircraft Systems (vsUAS).

- Defence Aviation Safety Authority. (2023). Defence Aviation Safety Regulations (DASR). Available at: Home | Defence Aviation Safety Authority

I am interested in the use of drones for logistics, surveillance and welfare purposes.

There are some allied applications/issues that deserve further elaboration in the contact of Australian arm forces:

* tethered drones - these can be planted and activated as required.

* Use of drones in medical assistance;

*marine drones - a lot of military action is in coastal zones or adjacent to wetlands/ waterways. To have a marine drone capability could be critical for operational effectiveness.

*The integration with of AI with drone technology. This is a hugh subject but of critical importance.

As your essay ends - it is time to get to work - happy to discuss further. I can supply you with a phone connection if you are interested.

Regards

Derek Sinclair