Defence recently celebrated its highest recruiting numbers in a decade. This above-expected growth is excellent news and goes a long way towards solving at least 50% of our recruitment and retention problems. Among the things listed that have helped, these figures are “retention incentives” like the continuation bonus and Defence Assisted Study Scheme. If nothing else; this proves that financial incentives (both direct as a cash bonus and indirect as the value of higher education) work.

Tangible rewards can be incredibly powerful, not for the item itself, but the symbolism of recognition of service or acts. Part of the reason the Australian Defence Medal was introduced was to ensure that everyone who performed their duties in the ADF could be recognised and proudly show this off at events of commemoration or remembrance.

Unfortunately, the process for awarding items such as commendations and medals is long, difficult, and rather opaque. Anecdotally, some medals for events, activities and operations as cut and dry as the National Emergency Medal have a backlog of close to three years after the event. This delay in recognition may detract from feeling of being organisationally valued that underwrites the retention of serving members. There is a plethora of research into human psychology surrounding the importance of giving good feedback in a timely manner and I do not believe that any period longer than six months should be acceptable with the exception of awards that require exceptional scrutiny (i.e. the Victoria Cross and other medals of Gallantry/heroism). I have personally witnessed the impact the delay providing medallic recognition through putting forward the paperwork to nominate three of my soldiers for commendations (one at each level) in February of this year with no feedback from the stakeholders involved in the awarding process. This lack of feedback is disruptive as a leader and manager, through being unsure if nominations were denied out of hand because the justifications were insufficient or if they are all approved and being withheld for a special event in which to award them.

This brings me to my second issue: the awarding of commendations is significantly dependent on the nominator’s ability to write persuasively. Writing is a skill that not everyone practises and not many people possess; this unfairly disadvantages the subordinates who may be performing highly but cannot receive the recognition they deserve because their NCO or junior officer cannot sufficiently advocate on their behalf. This is then exacerbated by the aforementioned opaque awarding process, which does not give feedback to the nominators to inform as to where future nominations may be improved or sustained. This culminates in unappreciated and demoralised soldiers who feel little incentive to stay in an organisation that is not fast enough to provide the tangible recognition of their hard work.

Third, commendations and medals are typically awarded for short stints, single events, and one-off acts. There are currently limited mechanisms to recognise good, consistent hard work for individuals; detracted particularly by both the asynchrony of postings between managers and subordinates and further detracted when opportunities to display one-off deeds of high performance under operational circumstances are becoming fewer as deployments become increasingly uncommon or linked to training activities not considered for medallic recognition.

This essay is not meant to be a treatise that lambastes the Honours and Awards Cell of each service as I’m sure like most of us they are understaffed and under-recognised themselves; but to offer alternatives that should help lighten the load. The reward for sprints to immediate actions can be rewarded; but it’s incredibly difficult to justify rewards for marathon efforts.

Recognising Soldiers – The Good Conduct Stripes

Queen Victoria herself commissioned the Victoria Cross during the Crimean War because she saw a lack of opportunity to recognise soldiers for their efforts in the face of the enemy. We’re coming towards a similar intersection of formal recognition in which we no longer have despatches to mention soldiers in and our operational context both in the Australian theatre and overseas has broadly shifted outside the bounds in which our Honours and Awards were designed to recognise. Where warfare has adapted outside of drawn battle lines and mass conflict, so too should our recognition of good work away from the face of a uniformed enemy.

In Defence, we commonly conflate performance recognition with the role of a manager and leader to guide suitable candidates to promotion as, on the surface, this recognises people who are acting in accordance with our values (after all, you can’t promote if you’re on a Formal Warning) and performing at a capacity for higher rank. This provides both financial recognition (a boost in pay) and opportunity for further performance (with the added responsibilities commensurate with your new rank). Unfortunately, this creates two other problems not unique to the Defence enterprise. The Peter Principle (people are promoted to their level of respective incompetence) and simply that many employees simply do not want to make a change from the duties that they were recruited to or find professional satisfaction in. A personal experience of this as a fresh lieutenant was to convince an experienced and capable craftsman to go on his Subject 1 course for corporal. After I gave him the pitch of why lance corporal would be good to aim for after his 10 prior years of service, he simply replied “Sir, I get to rock up at 7 every morning, do PT with my mates, get on the tools all day and get out in time to pick up my kids from school; I don’t have to stay back like you, the corporals and ASM do, why would I want to change that?” Frankly I didn’t have a good answer for him and gave me an early and valuable lesson; not everyone needs or wants to promote to be professionally satisfied and there needs to be a mechanism to still recognise their hard work without giving them extra responsibilities that they might be unwilling or unequipped to deal with.

This openly opposes the oft-held view that those who refuse promotion are somehow professionally inferior or not suitable for the organisation. The argument that it is the professional responsibility of well-performing members to promote and inculcate their competence to junior Defence members fails to recognise two considerations: the need for a professional core of experienced members within all ranks to provide consistent production as other members promote and develop; and the importance of a separate cadre of members who are both competent at their core role, but also effective in instruction and development. Equivocating core job-competence with instructional ability risks detracting from the learning and development of junior members in order to satisfy a misguided requirement.

The solution to the aforementioned problem, as with many things in life, already existed in the past. The Good Conduct Stripe.

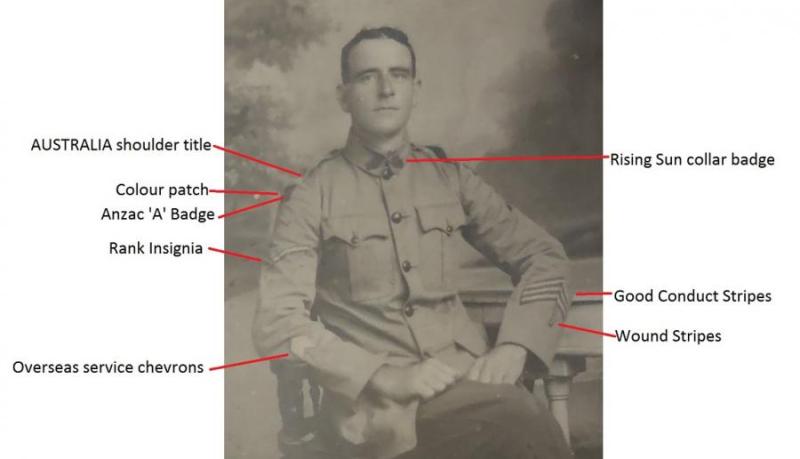

Introduced in 1836 across the Commonwealth (including Australia) and still technically in British custom (though functionally obsolete after 1970); Good Conduct Stripes (GCS) were an extra insignia worn on the lower sleeve of the uniform jacket (alternated from left to right during its history) awarded to private soldiers and lance corporals for service lengths of 2, 6, 12, or 18 years without being subject to formal discipline. It provided a small pay bump (likely equivalent to a single increment in our current system) as an incentive, and with the loss of a stripe for each infraction or all of them in the case of a Court Martial. They were all removed upon promotion to corporal with the belief that NCOs would be promoted for good conduct and merit and demoted as punishment.

My proposition would be similar but with the principle of “easy to get, easier to lose.”

A GCS would be awarded to anyone ranked sergeant or below (I believe a warrant supersedes the recognition and prestige that any GCS could confer) every two years (making it a good half-way point for an Australian Defence Medal) with pay increment boosts for the first two GCS awarded. These would be lost for any formal disciplinary charge with the associated loss in pay (i.e. a soldier with 4 GCS would go back to thre and only have one pay increment higher than a soldier with none) this could be re-earned two years after the charge, keeping the maximum increment boost at two. GCS would be retained on promotion; however, the increment boosts would need to be re-earned at the 2nd and 4th years of good conduct after the promotion. At every 6th stripe, a new colour would be awarded that replaces the first (i.e. after getting five black stripes, a silver one would replace the bottom black one), keeping the maximum number reasonable for the average forearm. These would be ordered in seniority from black to silver, finishing with gold (muted in colour and shine for the field uniform). They would be worn on the right arm and sewn in (giving an added aspect of visibility for when they need to be removed, further discouraging poor conduct) to both the field uniform and Service Dress tunic, though not the combat shirt nor the long sleeve polyester shirt. Upon promotion to WO2, all are to be removed.

Those who promote to WO2 or discharge with 6 or more (i.e. one or more silver) should be awarded a Good Conduct Medal (Second Class), those with 11 (i.e. one or more gold) or more a Good Conduct Medal (First Class) and those with 15 (i.e. all gold) a Good Conduct Medal with Wattle. These medals could be upgraded with the commensurate number of years’ service after the person has promoted so as to not discourage promotion in order to receive a higher grade of Good Conduct Medal.

Having such a visual representation of consistent, high quality work – with the ability for them to be taken away by behaviour not aligned with service values – provides the carrot and stick that would encourage people to perform with excellence at their current job whilst providing recognition on a more intermediate basis in a minor way outside of the awarding of the Australian Defence Medal (ADM) and the Long Service Medal. Many soldiers who don’t want promotion do not have much incentive to stay and retain their corporate knowledge within Defence between the 4 and 15 year mark. I think that this system will provide visual representation to those that might be becoming disillusioned and feel overlooked by their hierarchy. Especially by taking away any requirement for a senior NCO or officer to apply for this recognition; but with the ability for them to take it away (with just cause) makes this an “opt-out” system like the ADM rather than an “opt-in” system like a commendation. This allows it to capture the “silent performers” that deep down everyone knows deserve recognition but are so frequently forgotten.

The Brevet System – an older solution to new problems

Breveting has a long history among European (and European-adjacent) armies. Everyone takes the concept in different directions; but, defined simply, it is a warrant which gives commissioned officers a higher military rank as a reward without necessarily conferring the authority and privileges granted by that rank. Whilst defunct in most modern militaries; it presents an interesting starting point for the ADF to adapt for our own purposes.

From an Australian perspective, it’s important to note the way that the concept of a warrant has changed over the years. Because we have two different grades that confer two permanent ranks, most do not understand that historically a warrant was issued on a temporary basis to confer upon a senior sergeant some of the roles, duties, and responsibilities typically associated with a commission in order to carry out the duties of command or quartermaster – most obviously in the cases of Company/Regimental Sergeant Majors and the various different types of Quartermaster Sergeant Majors. Should this person’s role or duties change significantly, a fresh warrant would be issued to reflect that. This allowed for a formal conference of authority and a recognition of expertise that goes above and beyond that of the wider enlisted ranks. I believe that we can use a breveting system to achieve similar, but much more temporary, outcomes among commissioned officers.

I would define an Australian Brevet (Bvt.) officer as being “a temporary warrant conferred upon any officer as a recognition of their skill, effort, knowledge or experience that makes them senior among peers; though inferior amongst their new substantive officer cohort.”

In succinct and practical terms: a brevet officer would be a senior (not necessarily in experience/age but in merit) member of an officer rank that would wear and be referred to by a rank one level higher as a recognition and reward for reasons determined by their commanding officer (be they unit CO, brigade commander, division commander etc). I would have them wear the rank slide of the breveted rank; though it would include an additional device that would mark them as being non-substantive. Ideas for that could be a single wattle leaf or similar piece of Australiana flora attached to the top of the rank slide as a pin. This has precedence as the Governor-General has a whole wattle cluster as his or her rank insignia.

They would receive a pay increase set permanently at the bottom increment of their breveted rank – i.e. a major that is now a Bvt. LTCOL on Pay Group 3 would receive increment zero of Pay Group 3 for LTCOL no matter how many years they are breveted. In terms of a NATO rank structure, they would take the O number of the breveted rank to ensure that if they are being breveted to replace someone of the substantive rank, they will have no issues with delegation authorities that might be kept at a certain level. This would be tri-service though I have used Army-centric examples.

The way I envisage this operating is similar to how we can have many WO1s posted to an area, but they still have a set hierarchy amongst themselves with the band system. For example, an ASM or RQMS wouldn’t challenge the RSM – neither would a Battalion 2IC breveted to be LTCOL challenge the unit CO.

I would not want to see this as a default or assumed reward simply for taking senior positions – i.e. “I’m the adjutant, therefore I deserve to be a Bvt. MAJ simply to have more authority over the other O3s in my workplace” – But this should instead be conferred on hard workers for whom the CO believes is ready to start the transition towards their next higher rank and a way to test whether they are ready for the added responsibilities early.

I foresee this system as an effective manner in which to reward performance, add a carrot and sense of advancement to consistent workers and, most importantly, groom our officers into more senior positions and authorities on a trial basis that can be retracted if they are not ready yet. The best rewards are the ones that can be taken away for negative performance, and for those who value seniority and visible recognition of their efforts, a breveting system would enable this greatly.

As our ADF grows itself again in the face of increasing international tensions, we need to be prepared for concepts like “time in rank” or “minimum postings” to be phased out in preference of a more qualitative approach that can be enacted more quickly and by direct commanders than what we have now. Imagine a scenario in which a unit CO is injured and will be out of operation for a long time. Instead of a provisional promotion (which this system would not seek to replace by supplement) that would need to be issued by DOCM-A, the brigade commander could simply issue the OPSO of that unit with a brevet rank of LTCOL and allow them to get straight into business of command without concerns about delegation authorities or other administrative hurdles that would prevent a substantive O4 from unit command.

Conclusion

Our ADF is required to grow to 69,000 by the early 2030s. To achieve this we can’t just be bringing in new people and bleeding corporate experience at our senior ranks. Enabling the recognition of efforts at the lowest through middle of our organisation is essential to maintain growth and experience. Unlike larger organisations we cannot simply hire external talent into senior jobs; we grow generals, we don’t hire them. But just as we need to develop our officers into strategic thinkers at the highest levels of warfare, we must also recognise that not every soldier we recruit in the next decade will become an RSM. Sustained competence and character deserve recognition just as our highest acts of valour do. A private soldier being contented with a multi-decade life dedicated to the service of their country should be seen for the hardworking soldier that they are, not looked down upon for not burning themself out chasing promotions and advancement that they may not have the aptitude for.

An extremely select group of people have won the VC or Medal of Gallantry, but a lot of people work extremely hard to make the wheels of the Australian War Machine keep turning to get them to the front. The recognition of sustained, competent service is essential to retention and morale and Defence must evolve its systems to reflect this.

I believe good conduct stripes still resonate because they reward something that remains hard to measure in other ways, namely sustained professionalism over time. They reinforce the idea that turning up, doing the right thing, and maintaining standards year after year matters just as much as short bursts of high performance. That said, they risk becoming hollow if they are seen as automatic entitlements rather than meaningful recognition of behaviour and values.

If the modern military wants to reward both “marathons and sprints,” the principle is sound but the mechanisms matter.

Recognition systems must be clear, equitable and aligned with contemporary expectations. Consistency should be rewarded, talent should be developed, and flexibility should never come at the expense of fairness or trust in the system.

A very interesting article and one of a few that I have read that address ways in which we could recognise and reward Our People as a means to encourage retention.