Introduction

EX BROLGA RUN 24 proved 3 CER’s tactical gap crossing capability with the establishment of a Dry Support Bridge (DSB). The exercise successfully illustrates the value in tactical close support bridging operations in enabling tempo, adaptability and capacity of the Brigade in offensive and defensive conventional operations. The lessons learned in the application of natural wet gap obstacle breaching, broken down in this article to section, troop, sub-unit, unit and formation level. Overall, the case study of 3 CER’s DSB employed in the Townville Field Training Area during Ex BROLGA RUN provides key lessons for planning and execution of the future application of Mobility effect to the fighting force in a conventional setting.

Case Study

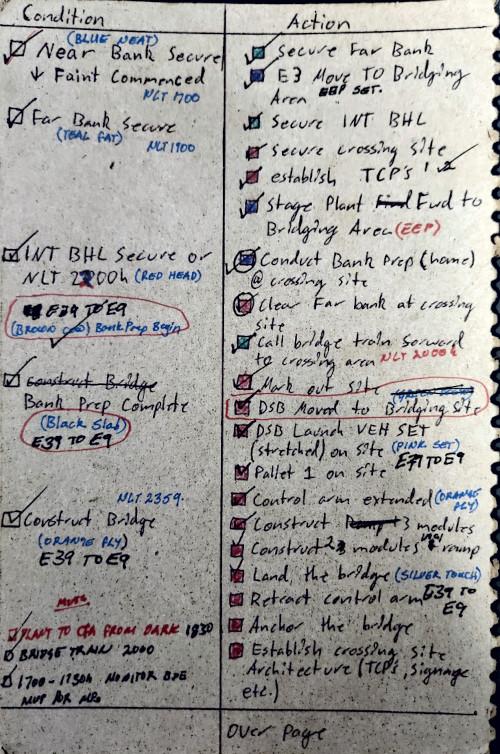

As part of a deliberate Brigade-level river crossing operation, 3 CER was tasked to breach Keelbottom Creek in a single period of darkness. The purpose of the river crossing operation was to project BG CORAL against the enemy from an unexpected direction and provide a lateral route in depth to reinforce and sustain the BDE subsequent actions. The gap crossing required the use of the DSB (Figure 1(a)) to emplace a 46m bridge (Figure 1(b)) on a restricted crossing site, allowing the passage of all 3 BDE platforms including Heavy A vehicles.

To meet the requirements of tactical situation, the combined arms crossing operation was planned and executed within a 72 hour window, with 36 hours from delivery of BDE orders to opening of the crossing site. Broadly, the BDE scheme of manoeuvre saw an Armoured BG (BG EAGLE) feint on the most likely crossing point to deceive the EN as to the location of the BDE Main Effort. BG CORAL constituted both the Security Force and the Assault Force, projecting reinforced dismounted combat teams to secure the home and far banks of the crossing area allowing the Crossing Force led by 3 CER to secure the crossing site, prepare the banks and emplace the bridge.

Specific to the crossing operation, a reinforced support engineer squadron (25 SPT SQN) consisting of combat engineering, plant and CSS elements occupied and established the crossing site, secured home and far banks of the crossing site, conducted bank preparation with plant and ultimately deployed the DSB over a single period of darkness. The launch and recovery vehicle (Figure 1(a)) suffered a mechanical failure after deploying the bridge and in the final stages of retrieving the launch beam. While this was recovered at a later date, it materially disrupted the viability of the crossing site and is an instructive lesson in the importance of operating multiple crossing sites for operations of this type.

Figure 1. (a) DSB night training in the CTA, TSV (b) DSB built over Wheelers Crossing during EX BROLGA RUN 24

Section Level Lessons

At the section level, a series of lessons can be taken away in achieving a successful DSB build to meet 3 BDE’s operational (training) requirements during EX BROLGA RUN.

The first is a dedicated time allocation to training by day and night; having certainty of time allocated to training allows section commanders to plan and execute training serials of increasing complexity by day and by night. This means training proceeds in a planned and methodical sequence ensuring that all section members are proficient at one milestone before moving onto the next. This was achieved during 2024 by first completing a comprehensive DSB course conducted on Ex DINGO FURY within the field environment, reinforced with further targeted training in barracks to produce a team ready to conduct the complex task in a tactical environment.

The second lesson at the section level sits with the effective reconnaissance of a crossing site with adequate planning at the section to troop level to enable efficient execution of the gap crossing operation. The conduct of a technical reconnaissance is vital in ensuring the feasibility of the DSB emplacement and its traffic ability. In retrospect, this reconnaissance should include an in depth assessment as to the requirements for development of banks, general site layouts (for example, turn around points, construction areas, etc) and communicate control measures to supporting elements. The information gained during technical reconnaissance at the section level is also critical to enable squadron/regiment and subsequently formation level planning, thus its importance is difficult to overstate.

Finally, communication through application of Mission Command, was found to key to the successful gap crossing operation on Ex BROLGA RUN. Mission command delegated to a section commander by a troop commander, particularly when emplacing a specialist capability requiring niche training, is vital. The passage of information and translation of specialist technical knowledge into tangible actions, events and timings that chain of command can translate for planning is critical in enabling the timely and correct synchronisation of effects. Conversely, the adequate communication of effects, actions and timings down to the DSB commander is critical in understanding the overall execution of the task and allocation of effort. This example illustrates the distinction between section commanders being experts in operating a specific asset while the troop commander is the expert in its tactical employment as part of a broader team. This command relationship and passage of information was particularly effective on Ex BROLGA RUN 24 and a lesson worth emphasising for future gap crossing operations.

Figure 2. (a) Approach ramp remediation with ENGR plant, (b) Home bank seat remediation with RAEME Support.

Troop Level Lessons

In order for Specialist Troop to execute a complex gap crossing in a single period of darkness during Ex BROLGA RUN 24, a robust training program was reversed planned and implemented from January 2024. The identification of the operational requirement for emplacement of a DSB under tactical conditions in a single period of darkness guided the generation of key milestones in training to be achieved from the start of 2024. This enabled the training of personnel on a 3 CER led DSB course during Ex DINGO FURY, achieving a base level of qualified members to allocate to the task. Following this course, an accelerated training program was executed within Lavarack Barracks with the aim to achieve a section capable of constructing a 46m max length DSB, under BNVDs and in a time window of 6-8 hours. A key lesson from a troop perspective is the implementation of a reversed engineered training program, accountable to TP and SQN headquarters, to successfully achieve a clearly defined operational requirement by working backwards from the standard required.

As the crossing site commander, the DSB’s emplacement by night in a tactical scenario offered a complex challenge with a variety of key lessons learned. The cooperation in planning with SQN and REGT HQ in developing an EXCHECK (conditions and actions based checklist) was critical in enabling the application of mission command to the execution of the task. Having a seat at the table during planning, producing clearly defined objectives and conditions based events, enabled the TP HQ to coordinate the movement of supporting assets in a sequence that achieved a successful gap crossing operation whilst on a strict timeline. In terms of execution, Mission Command, directed down to the troop level, is crucial and a key lesson for Sub Unit Commanders to use when executing their course of action down to a Lieutenant.

Live experience within a field environment proved to be an exceptionally challenging but rewarding activity for the TP. Gap crossing is predominantly taught on ROBC as a complex theoretical exercise, however affords little opportunity to practically apply this knowledge. The opportunity for a TP of specialist Combat Engineers to coordinate various moving parts in order to achieve a BDE main effort was a valuable training experience that will provide all involved a baseline experience to draw from in years to come. The execution of the DSB construction on EX BROLGA RUN is a testament to the high quality of training that RAE JNCO’s and Sappers receive and their outstanding work ethic and character. During this particular DSB operation a section of soldiers and JNCOs worked tirelessly throughout the night. Even after the bridge suffered a mechanical failure during retraction, the soldiers were impressively stoic in their response to the situation and quickly reorientated to rectify the bridge and achieve the mission. Their quick reorientation and strength of character directly enabled the BDE to establish Ground Lines of Communication and a safety lane for subsequent live fire training. To conclude, the biggest lesson is that grit, quality of character, dedication and training gets the job done. The value of live experience over theory in providing engineering effects can’t be understated as an RAE Officer.

Squadron & Regimental Level Lessons

Two key lessons present themselves for Squadron and Regimental level engineer officers from the execution the gap crossing on Ex BROLGA RUN, being the importance of a fundamental understanding of doctrine, the application of directive command with disciplined initiative.

A fundamental understanding of engineer and combined arms doctrine was essential to enable the rapid planning cycle required. Holding a fundamental understanding of the doctrinal scheme of manoeuvre, tasks and control measures for a river crossing as opposed to a cursory knowledge of tactics taught on a course once but ‘data dumped’ can be described as the difference between genuine tactical acumen and tactical awareness. Holding this tactical acumen meant the squadron and regimental level officers involved – principally the CO, OC and OPSO – were able to commence planning immediately at their respective levels upon receipt of a warning order or earlier task direction. Despite this being conducted in relative isolation with limited touch points, similar planning deductions were made, creating a shared understanding and rapidly developed solution. As a notable example, the forces available combined with the terrain meant not all of the doctrinal objectives for a river crossing were required and two of these needed to be combined – concurrently and independently both the OC and CO & OPSO identified this with these modified objective assigned to similar terrain features. The effect this proactive planning with a common tactical acumen had was a rapidly delivered execution plan which won time for final battle procedure for the Crossing Force. Had the officers involved not maintained a tactical acumen and instead relied on tactical awareness, time would have been lost with unnecessary revision or worse still, having to be re-taught assumed knowledge instead of planning. While this seems obvious, there are sufficient examples of junior and field grade officers having data-dumped knowledge from earlier courses as unnecessary or not immediately relevant for this lesson to be worth covering.

The second lesson at this level was the benefit of directive control combined with disciplined initiative. The actions of the Crossing Force are initially carefully synchronised with the Deception and Security Forces to ensure both security of the operational plan (so as not to undermine the deception) and security of the Crossing Force itself. Once the crossing force is fully committed to the site, this reverses and the actions of the Security, Bridgehead and Breakout Forces are then synchronised with the actions of the Crossing Force to generate maximum tempo. Further, the actions within the Crossing Force itself are also synchronised with each other, particularly on a site with restricted space, thus ensuring the high value assets such as plant equipment or the DSB and its associated train or not exposed or congested.

This was achieved by enhancing the consideration of Centralised Control and Decentralised Execution with directive control and disciplined initiative. This was explained in Squadron level orders as Troop Commanders to contain their initiative to solving local problems associated with the specific task they had been issued at the time. This controlled the risk that an asset would be pushed too far forward too early on the initiative of a subordinate commander without full visibility of the situation. At the squadron command post, this was managed through frequent reporting and tracking progress against the shared EXCHECK. This approached achieved balance by providing Troop Commanders with clear scope to exercise their initiative resulting in acceptable tempo being achieved, security being maintained and the Squadron Command Post not being overwhelmed by minor issues.

Figure 3 – EXCHECK

Formation Level Lessons

Two key lessons can be taken for formation level planning, being the requirement for reserve crossing sites and redundancy assets and managing risk to generate tempo.

Objectively, the brigade river crossing did not achieve its planned tactical objectives due to mechanical failure of the DSB as described above; however, the Brigade achieved its critical training outcomes. That only a single crossing site was used, and there being only a single launch/recovery vehicle available meant there was no flexibility in the plan if a crossing site or critical asset was non-viable. This risk was assessed during planning and tolerated on the basis of meeting the desired training outcome of conducting a wet gap crossing by night as a Brigade tactical action and the combined absence of alternate crossing sites with environmental approval and suitable bridging equipment. There is a lesson in this for Army, in that ‘two is one and one is none’. If a Brigade is to be enabled to conduct bridging operations a minimum of two bridges are required.

Nonetheless, the risk was ultimately realised and at the worst time of highest consequence for the operation as the Bridgehead Force had been across the river and in contact for about 8 hours and in need of relief with no way to provide this other than over the crossing site. The Deception Force had become decisively engaged and was unable to constitute a relief force. The temporally late and unexpected failure required a rapid planning cycle to salvage the tactical situation and prevent the likely destruction of the Bridgehead Force – which the Brigade achieved.

Beyond the simplistic requirement for reserve sites or redundancy assets, the more prescient learning point can be found in the approach to tactical risk mitigation. The selected course of action required the acceptance of high risk to mission and force if the crossing failed. This could have prompted a scale of mitigations through CONPLANS to be enacted at different stages of the operation, the transition between these being informed by the EXCHECK. Developing CONPLANS as branches to the river crossing plan would be the most effective way of treating the risk necessarily accepted for this river crossing operation. However, the development of CONPLANS takes time and could have delayed the execution of the Brigade task, thereby incurring the risk of an enemy action changing the calculus on the battlespace.

The second lesson for formation level planning is how an informed acceptance of risk to generate tempo. As outlined when discussing directive control and disciplined initiative, the actions of the Security, Bridgehead, Crossing and Deception Forces were all highly synchronised. This is to ensure appropriate conditions were set to ensure the security of each successive step, and this was controlled through the EXCHECK. This conditions-based approach was planned to conform with time-based requirements to have the crossing operational by first light and this was articulated through orders – as an example:

“Action C is to occur when conditions 3.1, 3.2 and 3.3 are met, NLT xxxxh”

While clear if everything occurs as planned, this introduces a conflict if specified conditions would not be met by the NLT time. The BDE COMD made it clear during verbal orders that time was the paramount consideration, providing a clear priority. In practice this was executed between the Crossing Area Engineer (CO 3 CER) and the Crossing Area Commander (OC 25 SPT SQN). By constituting a quasi-Regimental HQ integrated with BDE COMD TAC, CO 3 CER was able to monitor the progress of other elements (the Deception, Security and Bridgehead Forces) which allowed him to assess the risk posed by conditions being not yet, or only partially met. Informed by OC 25 SPT SQN, he was able to know the progress of the Crossing Force and make informed, risk-based decisions to direct an action prior to conditions being met to ensure tempo was maintained and timings achieved. The level of detailed formation level planning conducted was the key enabler of this approach which worked well and ensured that, but for mechanical failure at the last moment, the crossing would have been achieved on time. Similarly, the clear direction from COMD 3 BDE that timings were paramount simplified risk-based decision making by subordinate commanders ensuring they were not unduly reliant on a conditions based approach at the expense of tempo.

Conclusion

The range of lessons taken from the employment of the DSB on Ex BROLGA RUN 24 from Section to Formation level demonstrate the complexity of combined arms river crossing operations. While the lessons drawn came from this specific example are most relevant to bridging, they are also more broadly applicable to preparing for and executing other types of combined arms operations or activities requiring a high degree of synchronisation. In particular, these include allocated time for section training, reverse planning the troop level training program, maintaining genuine tactical acumen as opposed to tactical awareness and the informed acceptance of risk to generate tempo in highly synchronised and time sensitive operations.

MAJ LJ Clarke & LT I Lumsden

25th Support Squadron, 3rd Combat Engineer Regiment