In a future Large Scale Combat Operation (LSCO) in the Pacific, interoperability between the Australian Army and its partners will be vital. In 2024, the 106th Battery of 4th Regiment, was able to test joint fire interoperability with its artillery counterparts in the Japanese Ground Self Defence Force (JGSDF). This article details the key interoperability lessons that were gained during 3rd Brigade’s war fighter exercises, Ex BROLGA RUN and BROLGA SPRINT. It focuses on the importance of fire support planning, bi-lateral teaming, signature management, and mission processing. The dissemination of these lessons will help to expedite the Australian Army’s interoperability in times of war. It is therefore intended that this article be instructive for other units preparing to train alongside the JGSDF or other Pacific partners.

Figure 1: Australian Fire Support Officer and Japanese FSCC Commander

Order of Battle

The JGSDF fires element comprised of towed 81mm and 120mm mortars, a Forward Observer (FO) team, and an Artillery Fire Support Coordination Centre (FSCC). On the Australian side, 106 Bty provided M777A2 howitzers, two Joint Fires Teams (JFT), an 81 mm mortar platoon, and a Joint Fires and Effects Coordination Centre (JFECC). Together, both organisations were responsible for providing fire support to Battle Group Coral (BG Coral), which also contained a combat team from Unites States Marine Corps, the US Army, and the JGSDF (CT Asahi). Exercise BROLGA RUN / SPRINT, held in Townsville Field Training Area (TFTA), provided the LSCO scenario under which all parties could train.

Fire Support Planning

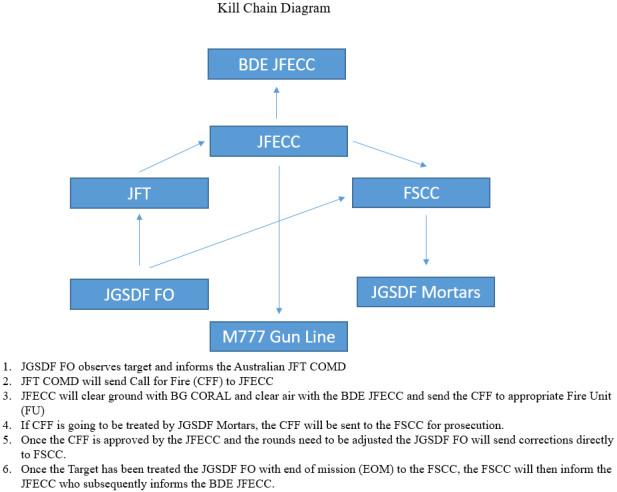

The Reception, Staging and Onwards Integration phase was critical for the establishment of role clarity between two culturally different armies, and the identification of friction points between our fires and effects procedures. Before deploying into the field, both parties formed a common understanding of how fire missions would be routed, processed and controlled. This was achieved through deliberate tabletop war games and joint fires rehearsals. During these rehearsals, the entire fires kill chain, from observer to fire unit was rehearsed both diagrammatically in the planning room, then again on the parade ground with all staff and Command Posts (CPs) present. These rehearsals enabled the identification of numerous procedural differences and the clarification of workarounds to facilitate fire support. The sooner these differences can be identified and treated, the less friction will be experienced during execution. As an example, some key differences that were identified were as follows:

- Different approaches to risk during danger close mission procedures

- Varying level of experience with urban fire planning

- Varying levels of experience with event-based, versus time-based, fire planning

- Different thresholds for unmasking artillery systems

- Different approaches to attack guidance

For instance, both parties identified and resolved major differences in how each nation verifies clear air before commencing an artillery engagement. The figure below outlines the fire mission routing that was agreed upon for the exercise.

Figure 2: Diagram of the fire mission routing employed for Ex BROLGA RUN

Battle Group Joint Fires Rehearsals

The value of Battle Group (BG) level joint fires rehearsals prior to each deliberate action was multiplied when ten-fold when a foreign language force is involved. The fires rehearsal enables artillery stakeholders to back brief the Battery Commander (BC) on their specific fires responsibilities by phase. They occurred in person post BG orders, usually around a mud model. The ability to visualise the joint fires actions on a mud model enhances battle visualisation and understanding. This emphasis on the visual dimension proved the most effective method of conveying intent to the JGSDF. During these rehearsals the FSCC provided important bottom-up refinement to the BC on the capability of their platforms, as well as planning refinements to their fire unit employment.

Bi-lateral Teaming

To combat language and procedural differences, both parties maximized bi-lateral teaming at every level. For instance, although 106 Bty was the senior artillery HQ, it was co-located with and worked in close coordination with the JGSDF’s FSCC. The Australian Fire Support Officer interfaced directly with his JGSDF counterpart. Australian JFTs also teamed with CT Asahi’s Forward Observers (FOs). This illuminated another procedural difference, being that Australian JFTs are more deeply involved in planning and executing operations alongside their combat team commanders. Despite the importance of teaming, it was still critical that a senior HQ was clearly delineated, being the 106 Bty JFECC, to ensure unity of command and clarity of intent. In multilateral activities, it was important to avoid undermining partner force procedures to an extent, so as to accommodate their unique training objectives. Teaming at every level proved critical, and was continually refined throughout to reduce the time to kill. Linguist Support

Mitigating Miscommunication

The frictions of training for high-intensity combat are multiplied when significant language barriers are introduced. Tactical planning was hampered by a shortage of linguists, particularly at the forward observer level, where fire plan design occurs. Several instances of fire order misinterpretation occurred, leading to delays in the kill chain. To combat the almost inevitable shortage of linguists, every opportunity was taken to rehearse both hypothetical and scheduled fire plans to a greater degree than considered normal in a unilateral battlegroup, which paid significant dividends. The other key mitigation is to factor in at least twice as much time to conduct mission planning iterations than what would be required for a English-speaking partner force. This is to afford time to clarify miscommunications and confusion that is unavoidable when working with another language. Miscommunication, friction and delay also originated from the movement of JGSDF fire units in an unfamiliar training area, often at short notice and at night. The greatest mitigation to this was the apportionment of guide vehicles, liaison officers, and traffic control wardens.

Figure 3: Australian and Japanese conducting a ROC drill for upcoming tactical actions for the MDB.

Mobility and Signature

While linking the JFECC and FSCC together served to significantly ease communication, an important tactical implication was the resultant increase in physical and electromagnetic signature. The FSCC comprised a similar configuration as the JFECC, being a vehicle command post with enhanced communications equipment. Planners must therefore factor additional time and space into position sighting and occupation to accommodate partner force systems. Planners must also anticipate differences in mobility and protection, as the JGSDF’s Toyota Mega Cruiser was not authorised for off-road driving and is completely unarmoured. These vehicle differences compelled the JGSDF to operate the FSCC in a dismounted configuration in certain phases, thereby reducing our tactical signature. Fortuitously, the mobility mismatch between our parties encouraged even closer integration and planning unintentionally improving joint fires lethality. The ability for the FSCC to operate dismounted was something they have never trained for and testified to their adaptability and professionalism.

Figure 4: Japanese Mega Cruiser (Left), Australian Bushmaster PMV (Right)

Fire Unit Advantages

The integration of foreign artillery systems presented several important opportunities. For one, the inclusion of both 81mm and 120mm mortars provided the battlegroup the ability to effect targets at range without exposing 3 Brigade’s howitzers to counter fires. The JGSDF enabled more devastating weights of fire to be brought to bear, as Australian howitzers and Japanese mortars frequently engaged targets simultaneously. This lethality was well demonstrated during the live defensive fire plans that occurred during Ex BROLGA SPRINT, where the firepower of Australian and Japanese fire units was brought to bear on multiple targets in rapid succession. A second opportunity was the ability to plan with novel capabilities. For instance, a notable advantage of the JGSDF mortars was their range. The rocket-assisted projectile of the JGSDF Type 96 120mm mortar increases their High Explosive (HE) range from 7.5km to 13km, which afforded a counter-battery asset that we typically do not train with. With this advantage came added responsibility to artillery staff and the battlegroup commander. Battlespace had to be apportioned in the form of primary and alternate firing positions, while time and road space were also required to facilitate movement and resupply.

Figure 5: 106 Bty M777A2 Howitzers and Japanese 81mm mortars suppress enemy assault forces with high explosive projectiles, while Japanese Type 69 mortars simultaneously blind enemy firing positions with white phosphorus.

Figure 6: Japanese Type 69 120mm towed mortar.

Mission Processing Refinement

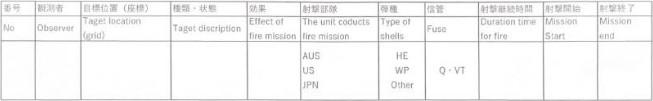

During both exercises we continued to refine how our different targeting cycles test our processes. Fire mission processing was helped significantly by the FSCC’s “fire mission slip”. This paper slip was written in both Japanese and English, thereby eliminating much of the language barrier and reducing the delay in mission processing. This also assisted the JFECC in understanding and tracking the use of the Japanese Mortars whilst also being able to confirm clear air and ground to facilitate engagements. Another key learning opportunity related to differing approaches to fire planning between both nations. While both nations were acquainted with time-based fire plans, the Japanese were less familiar with event-based fire plans, which offer greater flexibility to post H-hour modifications. The greatest challenge to mission processing was the incompatibility of the JGSDF and Australian gunnery computers. Security classifications and software prevented any form of digital interoperability, which is recommended as an objective for future training activities.

Figure 7: Japanese “Fire Mission Slip”

Figure 8: Dismounted FSCC and Mounted JFECC configuration within BG CORAL HQ during of conduct of the MDB on Ex BROLGA RUN.

Live Fire Validation

The live fire component of Ex BROLGA SPRINT served to validate the TTPs that had been developed over the preceding few weeks. The live fire scenario was a Brigade defensive fire plan that integrated Australian howitzers and Japanese mortars, JFTs, as well as tanks, and direct fire support weapons. In execution, Australian and Japanese fire units successfully engaged several scheduled and on-call engagements simultaneously as part of a dynamic event-based area defence. As part of a full battlegroup activity, Japanese and Australian FO’s were able to practice integration under realistic battle inoculation effects. Notably, it was the first time for many members of both nations conducting a bi-lateral fire plan, thus presenting a mutually beneficial training experience. The fire plan culminated in the conduct of several danger close engagements by howitzers, while JGSDF mortars shaped the enemy’s depth echelons.

Figure 9: Australian Battery Commander and Japanese FSCC Commander planning subsequent mortar step up positions at OBJ Bear.

Conclusion

Collaboration between the 106 Bty and the JGSDF, during Exercises BROLGA RUN and BROLGA SPRINT provided invaluable insights into the intricacies of fires interoperability with the JGSDF. Effective bi-lateral fires hinges on careful planning and integration with linguistic support. The experiences highlighted the effectiveness of detailed joint rehearsals and the need for robust SOPs to ensure seamless cooperation in the field. The adaptability and professionalism displayed by both forces, particularly in overcoming procedural mismatches was instrumental to tactical success. Future exercises should prioritise increased preparation time to refine procedures, and prioritise bi-lateral teaming, foreign weapon integration, and signature mitigation. Proactively identifying, mitigating and refining interoperability obstacles will significantly enhance the Australian Army’s lethality in high- end conflict.

LT Benjamin Stephens

BK 106 Bty, 4 REGT